The Irish taoiseach, Micheál Martin, put it politely. It would be “undemocratic” for the Democratic Unionist party to refuse to form an executive in Belfast after the elections, he said. But the DUP will refuse to enter an executive, now that Sinn Féin has massively outpolled it, and a majority of Northern Ireland’s people has voted to have as first minister a republican whose party wants a united Ireland. Sinn Féin gained an astonishing 29% of first preference votes in Thursday’s assembly elections. The DUP got 21.3%, a drop of 6.7% on its last performance.

That refusal, ostensibly a protest over the Northern Ireland protocol, will be even further good news for an already jubilant Sinn Féin, because it proves definitively to its voters that Northern Ireland, set up 101 years ago to be an exclusively unionist state, is incapable of becoming a pluralist one and must therefore be brought to an end. No wonder Sinn Féin’s president, Mary Lou McDonald, has already said that preparations for a border poll should begin immediately and that it could be held within five years.

Northern Ireland is one of the poorest regions in the UK and many of those who work with its most disadvantaged citizens are pointing out evidence that a growing number of people are living in what is defined as destitution. They cannot meet the basic needs of their families. This is not a good time to refuse to govern.

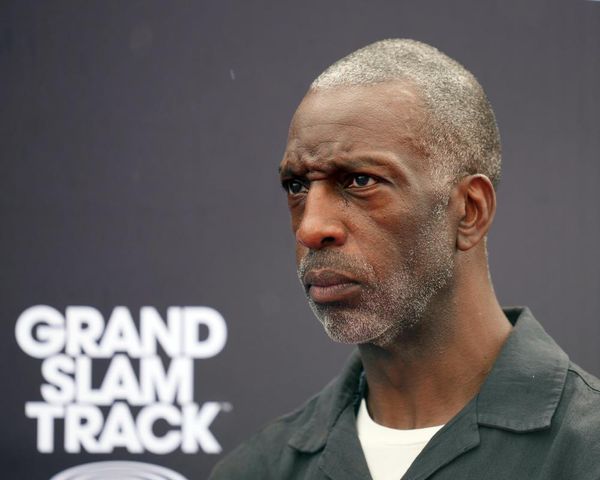

Under threat from the reality of change, unionism has hardened. During the election campaign, Jeffrey Donaldson, leader of the DUP, aligned himself with those extremists opposed not only to the protocol but to the Good Friday agreement and power-sharing. This was madness – the 1998 agreement protected unionist rights, whatever the constitutional future might hold. Donaldson’s support has worked not for his own party but for the hard-right Traditional Unionist Voice party, which increased its vote, though as far as seats are concerned it remains a one-man band. It will maintain its grip on the DUP. Its leader, Jim Allister, who is fiercely articulate in his aggressive nostalgia for the days of unionist dominance, has already begun to jibe at Donaldson about his post-election choices. He demanded to know if the DUP was now willing to be bridesmaid to Sinn Féin, with its MLAs as page boys and page girls.

Donaldson looks increasingly like Miss Havisham, sitting abandoned amid the mouldering ruins of the wedding feast. There is, we all know, no prospect that Boris Johnson will cease to be a cad. He casually let his suave best man Brandon Lewis reveal on Wednesday night that even his most recent promise would be broken. There would be nothing in the Queen’s speech about ditching the protocol, nothing to make it look like he even noticed the dilemma of the party that shafted Theresa May and got him into power. If it suits Johnson to use the DUP in its Brexit standoff with the EU, he’ll use it. Otherwise, his response to the DUP’s neediness is Rhett Butler’s to Scarlett O’Hara: “Frankly, my dear, I don’t give a damn.”

Donaldson would far rather stay at Westminster than return to Stormont. Another of Johnson’s broken promises (allowing double jobbing) means he must choose. Paul Givan, the first minister ousted when Donaldson pulled down the executive earlier this year, said last night the party leader should be at Stormont, more evidence that the party is still bitterly divided. This election has simplified the political landscape, while also making it more interesting, not least because of the massive success of Alliance, which has emerged as the third largest party. It takes no position on the constitutional question and draws voters from unionist, nationalist and other backgrounds. Alliance used to be the party that “nice” unionists said they voted for when they didn’t want to admit they voted for the Reverend Ian Paisley. Under the confident and progressive leadership of Naomi Long, it has attracted a broad range of people, including many young people from the Protestant community who have rejected the DUP’s fundamentalism and intransigence.

At Stormont, under the power-sharing arrangements established under the Good Friday agreement, parties must designate as unionist, nationalist or other. Alliance is “other”. It has surpassed even its own highest expectations, taking 13.5% of first preference votes and gaining numerous seats through transferred votes. The Social Democratic and Labour party and the Ulster Unionist party suffered devastating losses, even in their heartlands. The Green party lost its seat.

Long has been campaigning for a change in the power-sharing arrangements that recognises that the old binary no longer represents political reality and that her voters cannot be treated as lesser citizens whose representatives are not called upon when “cross-community support” is being measured. The success of Alliance will ensure that Sinn Féin and the DUP, should they form an executive office together, must represent the interests of a diverse society.

The lines by Yeats about the Easter Rising in 1916 and its aftermath are overused but in this case are apt. “All changed, changed utterly.” Northern Ireland has had a transformative election.

• Susan McKay is the author of Northern Protestants – On Shifting Ground