St-Pierre-Miquelon is a small French archipelago off the coast of Newfoundland in the northwestern Atlantic Ocean.

The territory is just 244 square kilometres with a population of only 5,800. Nonetheless, it’s recently been in the global spotlight due to its inclusion in a wave of tariffs imposed by the United States — and because of a controversial remark from a French presidential hopeful suggesting undocumented migrants should be deported there.

These recent events provide an opportunity to examine the complex historical and geopolitical entanglements surrounding St-Pierre-Miquelon and involving France, Canada and the United States.

Last French territory in the region

Visited by Indigenous Peoples for nearly 5,000 years, St-Pierre-Miquelon became known to European sailors in the late 15th century and was officially claimed for France by Jacques Cartier in 1536.

The archipelago soon emerged as a strategic base for French fishermen engaged in cod fishing and whaling. Over the ensuing centuries, the islands were fiercely contested by France and Great Britain, changing hands multiple times before being definitively restored to French control in 1816.

In the 20th century, the archipelago was at the heart of recurring fishing disputes between Canada and France.

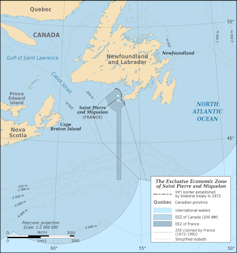

These peaked in 1988 with events that included the seizure of fishing vessels, the recall of ambassadors and violations of existing agreements. Despite historic treaty-based rights, France’s access to fishing grounds declined after Canada’s 1992 cod moratorium and an arbitration ruling that gave St-Pierre-Miquelon an exclusive economic zone of just 38 kilometres around the archipelago, except for a 16-kilometre swath extending 320 kilometres south.

Both these events had major economic repercussions for St-Pierre-Miquelon.

Hefty tariff

Today, the territory’s economy is small — less than 0.001 per cent of France’s GDP — and it depends heavily on public funds and external provisions, particularly from neighbouring Canada.

Nevertheless, the territory was initially included among the targets of the so-called Liberation Day tariffs announced U.S. President Donald Trump in April. It was singled out with a hefty 50 per cent import duty, temporarily making it one of the most heavily taxed territories in the world, matched only by the landlocked African country of Lesotho.

Although Trump reversed course and reduced the tariff to 10 per cent a few days later, the original decision was perplexing given the archipelago’s minimal economic weight and its peripheral geopolitical position. Why was this St-Pierre-Michelon targeted so brutally by the Trump administration?

Halibut geopolitics

St-Pierre-Miquelon and the U.S. had a balanced trade relationship from 2010 to 2025, until a sharp discrepancy appeared in July 2024. The U.S. imported US$3.4 million worth of goods from the islands, exporting only $100,000 over the entire year.

This resulted in a reported trade imbalance of 3,300 per cent for the year 2024, which the U.S. government appears to have interpreted as evidence of a 99 per cent tariff imposed by the territory, applying the same flawed algorithm on other countries.

Why was there such a discrepancy in July 2024?

According to several reports, this statistical anomaly is actually the result of a long-standing dispute between France and Canada over fishing quotas in the waters surrounding St-Pierre-Miquelon.

Traditionally, the territory mainly exports seafood products to France and Canada, and almost none to the U.S.

But in June 2024, a French vessel offloaded several tons of halibut — an expensive fish in high culinary demand — in Saint-Pierre.

While the catch was made in international waters and was technically legal, it occurred amid ongoing tensions between France and Canada over halibut stocks and the sustainability of the species in the area.

Because of these tensions, the catch was redirected to the U.S. market and sold for the aforementioned US$3.4 million, an outcome that ultimately triggered the tariffs imposed by the Trump administration.

France and Canada reached an agreement on halibut later in 2024. But their “halibut war” was just the latest example of recurring disputes between the two countries over fishing quotas in the waters off the Grand Banks of Newfoundland, one of the world’s richest fishing grounds.

The heavy tariffs imposed by the U.S. on St-Pierre-Miquelon, even though they were swiftly reversed, wer therefore an indirect consequence of the long-standing tensions between France and Canada.

A new Alcatraz?

Within days of St-Pierre-Miquelon recovering from the tariff shock, it was once again thrust into the spotlight.

This time, Laurent Wauquiez, a moderate right-wing presidential contender in France, suggested migrants under deportation orders known as obligations de quitter le territoire français — or OQTF — should be given two options: either be detained in St-Pierre-Miquelon or return to their countries of origin.

It’s not the first time politicians have proposed deporting prisoners to French overseas territories.

The suggestion is aligned with France’s historical use of these territories as sites for penal colonies, most notably in Cayenne in French Guyana and New Caledonia in the South Pacific.

Wauquiez’s remarks were widely condemned as contemptuous and colonial in tone, including by members of the government.

In response, local authorities in St-Pierre-Miquelon tried to capitalize on the controversy by launching a humorous media campaign that reappropriated the OQTF acronym.

Their goal was to shift the narrative and highlight the archipelago’s appeal: low unemployment, strong public safety, outstanding natural landscapes and a peaceful, family-friendly quality of life — and, hopefully, free from hefty American tariffs.

Paco Milhiet does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.