Three people are feared to have died in NSW as floodwater inundates Central West towns just 2.5 hours north of Canberra. With showers and thunderstorms continuing across parts of the state this weekend and evacuation orders in place in Forbes, emergency services are bracing for another nervous week ahead.

The latest deluge has renewed talks of buybacks for flood-affected properties, new laws to prevent houses being built in high-risk areas and a rethink of climate and disaster risk when planning housing developments.

While informed engineering in Canberra's development is expected to have reduced the risk to suburbs identified as flood-prone, growth currently outstripping the national pace means where new houses go up is being closely scrutinised.

Population boom, coupled with climate change, has increased the need for the revision of flood estimates currently underway in parts of the ACT.

Why is Australia experiencing so many floods?

The disastrous consequences of Australia's third and current La Nina event really began to be felt towards the end of its second year.

University of NSW environmental engineering expert Ashish Sharma said the prolonged period of wet had created the worst possible soil situation - known as antecedent moisture conditions - as the air space required to absorb rain all but disappeared.

Higher temperatures as a result of climate change meant more moisture was being stored in the atmosphere and the soil just couldn't cope when it all came pelting down at once, he said.

"It's like a recipe for flooding," he said.

"And that is what we're seeing across the country."

Climate modelling suggests warmer Pacific Ocean temperatures in the central and eastern tropics and increased frequency of El Nino southern oscillation. The likely result is more La Ninas, more often, in Australia.

Is Canberra a flood risk?

Seven people were killed in Canberra when the Yarralumla Creek broke its banks and storm waters half-a-metre high crashed over the Woden intersection onto Melrose Drive in 1971.

The tragedy raised questions at the time over whether development of the suburbs had outpaced upgrades to the valley's ageing infrastructure.

Canberra's second major flooding event was recorded in the Sullivans Creek catchment in 2018. Streets flooded and homes were damaged in several suburbs, including O'Connor, Lyneham and Turner.

The repair cost at the Australian National University alone ran into the millions, when 11 excavators working at the site were written off and half a metre of water swept through classrooms and a campus library.

Both the Sullivan and Yarralumla catchments are considered a one-in-100-year risk of flooding. Both regions are poised to take in thousands of new residents in the next few years, with between 17,000 and 21,000 new homes proposed for the inner north alone by 2063.

The 1500 proposed for the new suburb of Kenny have been delayed due to ongoing investigations into ecological and "water matters", while Canberra Racing's push for its commercial and residential plans for Thoroughbred Park has faced its own obstacles.

An ACT government spokesperson said a study was under way to revise the flood estimates for the Sullivans Creek catchment, accounting for potential drainage system blockages and climate change.

"Suburbs in the Sullivans Creek and Yarralumla Creek catchments and elsewhere in the ACT are generally well-protected from flooding as a result of a legacy of good planning," a spokesperson said.

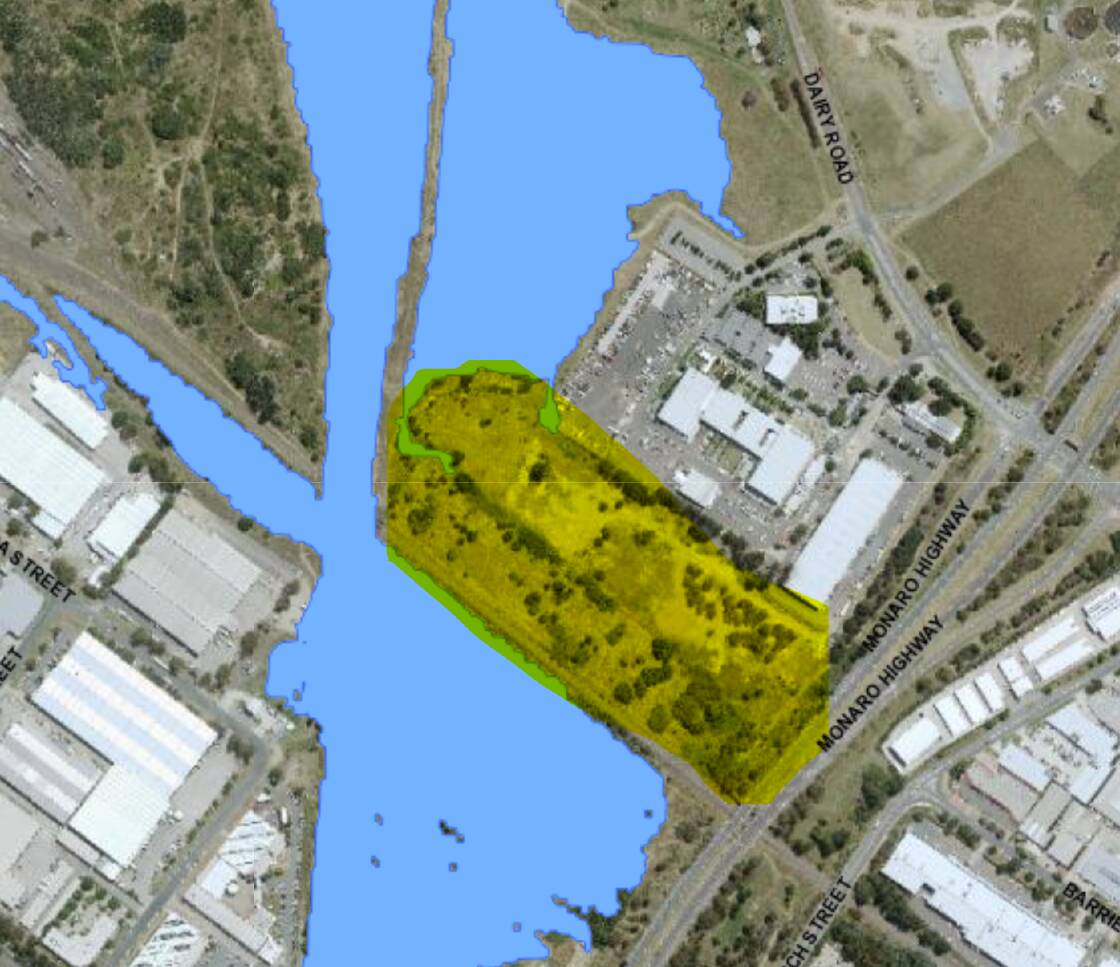

Flood studies undertaken in Canberra over the previous decade have identified low-lying areas at the entry to Lake Burley Griffin, the Jerrabomberra wetland, to be at some risk of inundation in the event of a one-in-100-year flood.

The mapping, updated as improved hydrological information becomes available, acknowledges urban changes including reduced vegetation, new roads, footpaths and urban infill, can influence flood risk.

A 500-dwelling development on Dairy Road sits just outside the area identified as at risk during a major flooding event.

A spokesperson for the developer said environmental assessments over three years, including the flood risk, had passed expert scrutiny by relevant agencies within the ACT Emergency Services Agency.

"The location of the site next to an ancient water channel, its elevation above flood levels, and the recent assessments and authority scrutiny at each stage of the development process confirms that Dairy Road businesses and future residents are not at risk," a spokeswoman said.

Parts of Narrabundah, Acton and the Parliamentary Triangle are also identified as at risk of flooding based on the one-in-100-year probability, modelling some experts now question when it comes to planning.

Rethinking the one-in-100-year probability

Professor Sharma said rules that once determined planning for cities considered low risk may no longer apply.

"The role of a civil engineer has historically been to provide safety and security to the civil population by building infrastructure so water supply failure or flooding is not faced by the average person," Prof Sharma said.

"The problem is that since all this infrastructure has been put in place, climate change has happened and climate change has messed things up."

In Canberra, the experts responsible for assessing the capital's flood risk have also acknowledged climate change is predicted to lead to more intense storms in the ACT region, with the potential to increase the chances of flash flooding.

A joint ACT and NSW climate change impact assessment found changes in rainfall patterns had the potential for widespread impacts, including floods, water quality degradation and soil erosion.

Operated by the National Capital Authority, Scrivener Dam plays a central role in preventing Lake Burley Griffin spilling into surrounding suburbs.

The National Capital Authority said the dam was capable of passing a flood of roughly 5000 cubic metres per second, a roughly one-in-10,000-year AEP or annual exceedance probability, while maintaining the lake level at the dam.

In other words, very large and rare inflows of water are required to back up behind Scrivener Dam for the lake to rise above usual levels. Current modelling suggests the probability of this happening is about one-in-10,000 in any given year.

"The NCA undertakes a rigorous monitoring and maintenance program to ensure Scrivener Dam can operate as required to maintain the level of the lake and to pass significant flood events," a spokesperson said.

"The NCA has also embarked on a landmark strengthening project for the dissipator of the dam to ensure the dam remains safe in extreme flood conditions."

Prof Sharma has coauthored new research that found the rainfall model engineers use to design large dams should be updated to take into account increased atmospheric moisture.

The study found the upper limit used to design spillways in dams all across the world was expected to increase by up to 38 per cent by 2100.

Prof Sharma said the result was the probable maximum flood would also go higher.

"They really consider this upper limit as the basis for ensuring that level of reliability or security is provided," he said.

"People live downstream of a dam because the risk of failure is considered so low, but that risk is increasing because this upper limit is going up."

What's being done to reduce the risk?

Barry Croke is involved in several projects through the federal government's National Emergency Management Agency, producing guidelines for flood mitigation through hydrodynamic and catchment-scale modelling.

The Australian National University associate professor has previously been involved in ACT groundwater management and monitoring the water quality of its catchments. His work has also given him first-hand experience of flooding in Queanbeyan.

Dr Croke said town planning in NSW was based on the probability of a one-in-100-year flood, as is the case for new suburbs in the ACT.

In addition to the problem climate change had created for that modelling, how the modelling was created to begin with was also potentially problematic, he said.

"In order to get a good idea of what the 1 per cent AEP flood is, you actually need thousands of years of data," he said.

"The implications for planning is that if you're unlucky enough to have a few events above the 1 per cent chance then your current estimate of that 1 per cent chance will be high and you'll be conservative in your planning.

"If you haven't seen one then your estimate will probably be low, in which case you'll be at a greater risk of flood impacts."

Dr Croke said development based on a 1 per cent flood probability still meant accepting a 1 per cent chance of failing.

"Selecting a flood level means you're accepting that probability of your system not being able to handle the floods," he said.

"I would argue very strongly that we need to take a more conservative approach and go up to a significantly higher flood level in planning how we lay out towns."

Dr Croke said the problem was planning had already been done to a large extent, meaning floods like Lismore had devastating effects, despite being considered very rare events.

He said rainfall there was based on the Bureau of Meteorology's intensity duration frequency curves of about a one-in-2000-year event.

"This is the thing, these rare events do occur," he said.

Dr Croke said flood damage mitigation involved designing buildings with bottom floors that were easily able to recover from being inundated with water and spaces like the Kambri amphitheatre, which were designed to flood.

His nature-based solution work includes designing wetlands that slow down flood waters to prevent sharp-high peaks that run through the system and instead create longer peaks at lower levels, examples of which can be found in the ACT.

Asked whether he'd purchase an apartment backing onto the Jerrabomberra wetlands, Dr Croke said it would be taking a gamble.

Kenny was probably less of a risk, he said.

Dr Croke said due to new concrete and bitumen increasing the speed at which water moves off surfaces and increases flood peaks further down, it was about designing structures like wetlands, to slow it back down.

"Again, it kind of comes down to your acceptance of risk. But as we've seen in the last three years, we can get considerable amounts of flooding, partially due to climate change and partially due to the variability in the Australian climate," Dr Croke said.

"You can't look at a single event and say, 'This was climate change', but can look at a huge number of instances and say, 'This is worse than what we've seen in the past'."

We've made it a whole lot easier for you to have your say. Our new comment platform requires only one log-in to access articles and to join the discussion on The Canberra Times website. Find out how to register so you can enjoy civil, friendly and engaging discussions. See our moderation policy here.