Aster G. Taylor is a Ph.D. candidate in Astronomy and Astrophysics at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor and a 2023 Fannie and John Hertz Foundation Fellow.

Darryl Z. Seligman is a National Science Foundation Astronomy and Astrophysics Postdoctoral Fellow/Assistant Professor of Physics and Astronomy at Michigan State University.

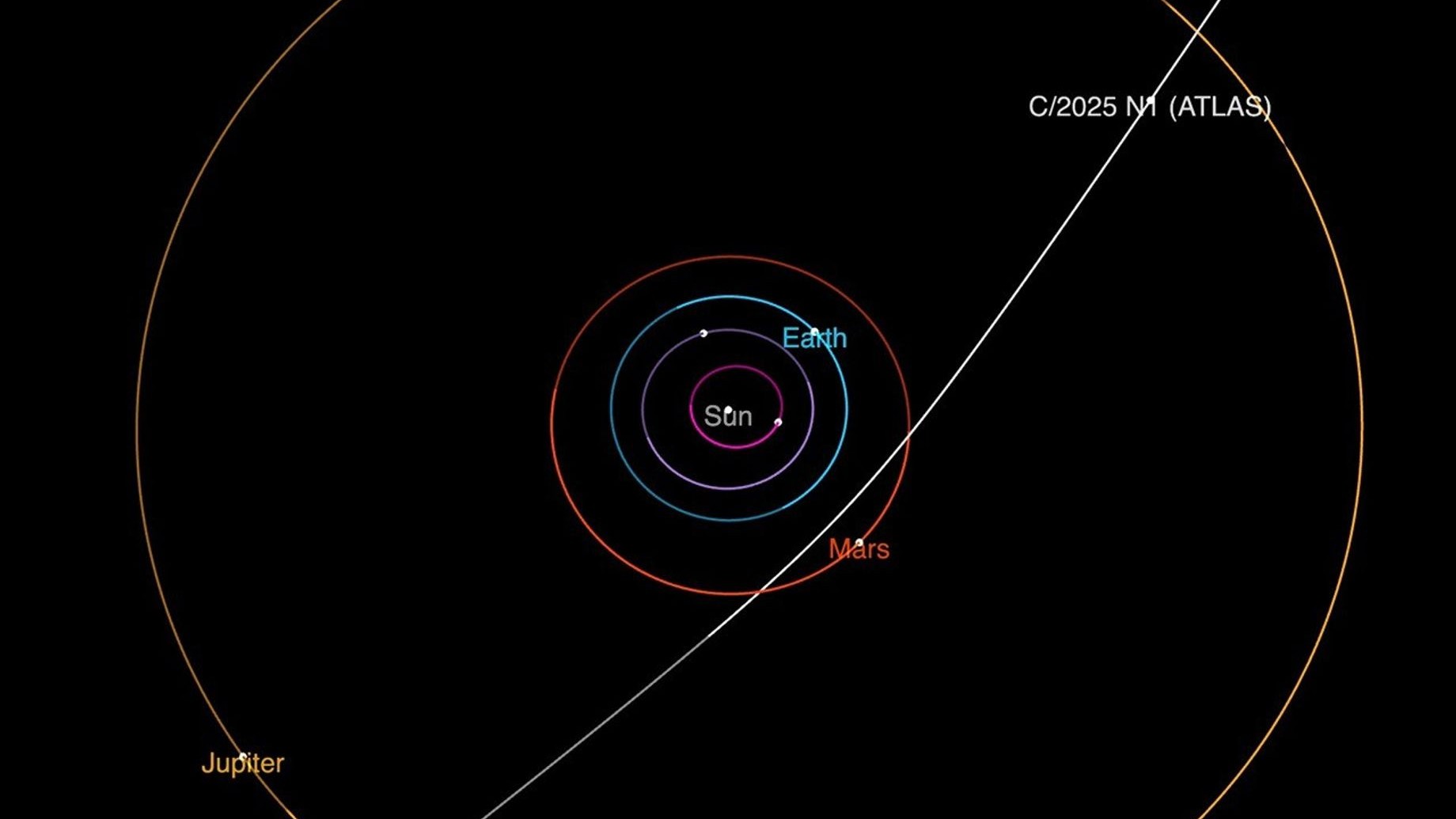

Recently, scientists around the world announced the discovery of 3I/ATLAS, the third known interstellar object to pass through the solar system. This discovery will have significant scientific impacts, advancing our understanding of how solar systems form and evolve throughout the history of the galaxy. 3I/ATLAS has also come at an especially auspicious time, given the recent advent of the Vera C. Rubin Observatory and ongoing difficult discussions on funding for the space sciences. The scientific and cultural impact of 3I/ATLAS over the coming months and years will serve as an exemplar of what astronomy can learn and why it matters.

Until recently, humanity had only discovered two interstellar objects — 1I/'Oumuamua and 2I/Borisov. Infamously, 'Oumuamua exhibited a mysterious nongravitational acceleration without a dust coma, which is still not well-understood. Unfortunately, 'Oumuamua was only detected after it had passed close to the sun, and it quickly became undetectable. As a result, there is little data on this object. Meanwhile, 2I/Borisov was a very traditional comet, albeit an extrasolar one. Although we understand more about Borisov, a sample of one understood and one weird object is not enough to provide any meaningful conclusions. The detection of 3I/ATLAS is a great improvement in this context — the detection of a 3rd object is a 50% increase in the sample size, and given the strangeness of 'Oumuamua, it effectively doubles the sample of understandable objects.

Even though 3I/ATLAS was only discovered recently, observations are already beginning to clarify the population of interstellar objects. Since 3I/ATLAS appears to be a comet, like 2I/Borisov, we can determine that comet-like interstellar objects are far more common than exotic ones like 'Oumuamua. In addition, 3I has an excess velocity of nearly 60 km/s (134,000 mph) relative to the sun. Since the influence of the galaxy tends to speed up objects over time, this velocity implies that ATLAS is far older than either 'Oumuamua or Borisov — around 3-11 billion years old. This fact alone tells us that interstellar objects were being produced relatively early in the lifetime of the galaxy, presumably along with exoplanetary systems. We can even begin to determine the distribution of these objects and infer the population of the still-unseen planets that must have ejected them into interstellar space.

And that is not all. Even though 3I/ATLAS was discovered less than a week ago, it will be observable for months to come. Astronomy's great instruments, such as the James Webb Space Telescope and the Hubble Space Telescope, are expected to reveal its size, composition, spin, and how it reacts to being heated for the first time. As the months pass and more data come in, we will peel back the mysteries of 3I and gain new insights into the workings of distant planetary systems.

It is a happy coincidence and a pointed lesson that 3I/ATLAS was discovered less than a week after the Vera C. Rubin Observatory came online, although Rubin did not discover this object. In Rubin's first 10 hours of observation, it found more than 2,000 previously unknown asteroids, and is expected to discover many more interstellar objects like 3I. As our catalog of interstellar objects grows, we will gain ever-increasing insight into these products of exoplanetary systems. As Rubin discovers these objects, the lessons learned from our observations of 3I will let us more effectively leverage our scientific capabilities to learn about these visitors.

At a critical moment, given the current Congressional discussions on science funding, 3I/ATLAS also reminds us of the broader impact of astronomical research. An example like 3I is particularly important to astronomy — as a science, we are supported almost entirely by government and philanthropic funding. The fact that this science is not funded by commercial enterprise indicates that our field does not provide a financial return on investment, but instead responds to the public's curiosity about the deep questions of the universe: Where did we come from? Are we alone? What else is out there? The curiosity of the public, as expressed by the will of the U.S. Congress and made manifest in the federal budget, is the reason that astronomy exists.

At a time when federal science funding is under threat, we are fortunate for the striking example of 3I/ATLAS. The public interest in this object and the sense of wonder that it brings can help renew public and political commitment to space science. In 3I/ATLAS, we see both the promise of astronomy and the importance of continuing its funding.