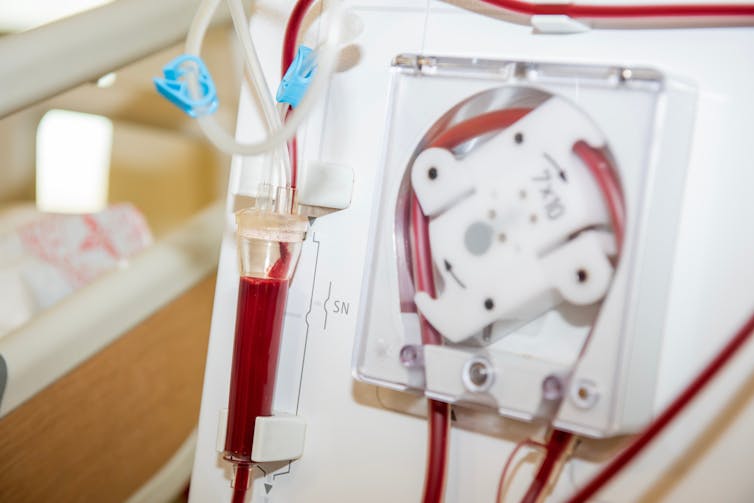

Every week, thousands of people with kidney disease in the UK spend long hours in hospital receiving life-saving dialysis. For many, this means travelling to a kidney unit three times a week and sitting through sessions that last four hours or more. It’s a huge commitment that affects people’s ability to work, travel and maintain a normal social life.

But for many with kidney failure, there’s another option: dialysis at home. It’s more flexible, often less disruptive and, in the long run, more cost-effective for the NHS. So why do most people still choose hospital dialysis?

A parliamentary summit in May reflected on how to make dialysis more accessible to patients at home. My colleagues and I published research on this topic in 2019. Working in partnership with people who have kidney disease, their families, NHS staff, dialysis providers and kidney charities, we explored the barriers to home dialysis, and how to overcome them.

People with kidney failure need either a transplant or regular dialysis to filter waste from their blood. Despite NHS guidance that at least 20% of people on dialysis should be supported to have this treatment at home, this target isn’t being met in many parts of the UK.

Our research team, which included people who had experienced dialysis, held discussions with 50 people from across Wales. Many told us that hospital dialysis was presented by healthcare staff as the default option. For those who had not yet come to terms with needing dialysis, or who had delayed planning due to the unpredictable nature of kidney disease, hospital treatment felt like the path of least resistance.

Some were concerned about the disruption home dialysis might bring. This included changes to their living space or worries that partners or family members might become their carers. Others valued the routine and regular social contact of hospital dialysis.

Healthcare professionals may unintentionally reinforce this choice. Some feel more comfortable monitoring patients in clinical settings or are unsure about how to support home dialysis effectively. In some cases, home dialysis isn’t an option because local services don’t have the infrastructure to support it.

Rather than simply identifying problems, we worked together to develop practical solutions. In 2021, working with patients, healthcare professionals, charities, commissioners and industry, we devised a new service plan that outlines how kidney services could be redesigned to support more people to choose home dialysis.

One important finding was the power of talking to others already doing it. It’s not just about practical advice, but reassurance that it can work.

We also identified the need for better training for both professionals and patients. People told us they wanted to understand their options earlier, ideally a year before dialysis starts. That means tackling difficult topics, such as advance care planning, sooner and with the right support.

Social care also has an important role to play. People with complex needs – like living alone, having mobility challenges, or experiencing financial hardship – may need home support, welfare advice or help navigating the system.

The cost of choice

In a linked study, published in 2022, we analysed the costs of different dialysis options. Home dialysis was found to cost between £16,000 and £23,000 per person per year.

Hospital dialysis costs more, between £20,000 and £24,000, rising to over £30,000 when ambulance transport is needed. This suggests that encouraging more people to have dialysis at home could deliver savings for the NHS.

In Wales, where all kidney services are coordinated through a single clinical network, home dialysis is more widely available. But in England, services are more fragmented, so access can depend on where you live.

Even if these changes were implemented, fundamental issues may still prevent progress. Beneath the surface of patient satisfaction lies a deeper problem – the NHS dialysis service is no longer working as intended.

Transport is one of the most frequently cited concerns among people receiving hospital dialysis, and no one seems satisfied with current arrangements. But satisfaction surveys fail to capture the complexity of the situation.

People often begin dialysis in a unit that isn’t closest to home due to availability. Later, when given the option to move closer or switch to home dialysis, they may decline. These dialysis units begin to function as surrogate families, offering comfort, routine and social interaction, especially for people who live alone or are isolated.

This emotional connection can obscure the bigger picture. Patients may focus on transport as the issue, rather than recognising that their own decisions – shaped by understandable human needs and system design – are part of the wider challenge.

Staff are caught in the same dynamic. They worry about losing patients they’ve built relationships with or fear someone may not cope alone. But as a result, the service ends up operating not to help people live well for longer but to preserve a sense of satisfaction with a suboptimal status quo.

By focusing too heavily on keeping people content with the status quo, we risk obscuring what’s truly working, or not. Worse, we may end up wasting already limited resources trying to fix problems that are byproducts of a system shaped more by sentiment than strategy.

Meanwhile, staff are caught in the middle, trying to deliver care under mounting pressure, with increasingly blurred expectations.

What needs to change

To break out of this cycle, different questions should be asked, and not just whether people are satisfied, but whether they are living well, maintaining independence and receiving care that truly reflects their needs and values.

Our research shows that people already on home dialysis are a valuable and underused resource. They can offer support and insight to others who are starting their treatment.

The collaborative approach we used could be a model for other parts of the NHS. By designing services with people, not just for them, we can move closer to a future where more people live comfortably with kidney disease, and care that truly fits around their lives and not the other way round.

Leah McLaughlin receives funding from Health and Care Research Wales. She is affiliated with the Wales Kidney Research Unit. We would like to acknowledge Dr Gareth Roberts Chief Investigator of the Dialysis Options and Choices study. Dr Gareth Roberts is a Consultant Nephrologist and Associate Medical Director at Aneurin Bevan University Health Board and is clinical lead of the Welsh Renal Clinical Network.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.