You can never rule Max Verstappen out, even when he's scrambling to overcome a car weakness. Several times during interviews this Formula 1 Qatar Grand Prix weekend – not one to waste a carefully formulated aphorism – McLaren CEO Zak Brown likened Verstappen to a character in a horror movie.

He was not referring to the schmuck who ventures down unarmed to investigate those noises in the basement just as the lights go out.

Verstappen and Red Bull might have seemed down and out after the Dutchman was outqualified by team-mate Yuki Tsunoda for the sprint race, where Verstappen salvaged fourth, complaining of horrendous bouncing throughout. But a targeted tranche of setup changes, including a higher ride height, mitigated some of the bouncing and enabled him to offer a genuine threat for much of GP qualifying.

Ultimately, it wasn't enough to defeat the two McLarens, even though championship leader Lando Norris had to abort his second push lap, clearing the way for team-mate Oscar Piastri to dig deeper and find enough to claim his first pole position since Zandvoort.

Understeer dogs Verstappen – and Norris

Not all of it was broadcast on Friday, but in every segment of the sprint qualifying session, Verstappen had complained about his RB21's aggressive bouncing. Viewing the onboards you could almost feel it as well as see and hear it, the telltale ck-ck-ck of skid plates and composite plank smiting the asphalt sounding like a cat snickering at birds through a window.

What this suggested was that Red Bull had tried to offset a known understeer problem through medium-high-speed corners – one mitigated but not solved by the new front wing added in Zandvoort – by running the car very low, seeking maximum downforce. But even though the team backed out of this slightly to reduce the bouncing that plagued Verstappen through sprint qualifying and the sprint itself, the Dutchman knew he would have to weather some bouncing because this was less of a hindrance to performance than the RB21's baked-in understeer characteristics on tracks such as this.

"It [the setup window] isn't a case of being ‘terribly hard' to find," he said in his post-qualifying session with Dutch media.

"But you have a particular problem in the car that you can't get rid of. In all those long, medium-speed corners you just have far too much understeer and that's just something this car has.

"Some circuits of course don't have such long corners, so it's a bit better there. Look, you always hope it goes a bit better, but you just can't get this out of it."

As to the bouncing, he was explicit about where this lay in the balance of performance issues he faced.

"It was a bit better [in GP qualifying]," he said. "A bit more controlled, but it was still there. But the biggest problem, of course, is the understeer you have."

On a track such as Losail, which was originally built to host motorcycle races, the corners flow into one another – and even taken individually, they are long and characterised by constant radii. That means an inherently understeering car's disadvantage compounds through the lap, a fraction of a second at a time.

It was a transient moment of understeer, rather than a consistent leakage of lap time, which undid Norris in Q3. He had been faster than Piastri in Q1 (albeit both outpaced by George Russell's Mercedes), but this was the second and only time – the first being SQ2 – that he would place ahead of his team-mate in the run-up to the grand prix.

After the first Q3 runs, Norris was fractionally ahead of Piastri, just 0.035s. Following a brief red-flag pause while debris was cleared from the circuit, Norris went out early to get his final run in the bag.

Despite having a clear track ahead (regardless of the silly scene that ensued in the TV pen, and went viral on social media, after a misinformed TV reporter suggested Russell had blocked Norris, Russell got well out of the way on the main straight), Norris required a lift in the middle of Turn 2 to quell understeer. He knew the lap was done and, lacking fuel to do another – so tight are the necessary margins – he headed back to the pits.

Fine margins define the McLaren fight

It's a curiously counter-intuitive feature of the Losail circuit that it offers high levels of grip despite the fact that the ultra-smooth surface has more in common with the likes of Las Vegas and Baku, where there is lower grip. Not only is the upper surface of the aggregate smooth, the macrotexture is tighter than at neighbouring venues such as Bahrain.

High-grip tracks play to Piastri's strengths. A firmly planted car, particularly at the rear, enables him to drive with the laser-guided precision, which is his hallmark.

"I think even when we were commenting on Oscar struggling a little bit [in the past five rounds], I've always emphasised that there are technical aspects in the way the drivers exploit the grip available and the potential in the car," said McLaren team principal Andrea Stella.

"And here in Qatar, we go back to the category of circuits with high grip. And in the category of circuits of high grip, I think Oscar is in his most natural way of driving the car, and he can really maximise the potential available.

"While we have said before that in circuits like Mexico, Austin, especially in terms of braking and rotation of the car, you need to start to slide the rear axle. It's kind of a different technique of driving a Formula 1 car, and it's a technique that Oscar is developing, but a category where Lando excels. So from this point of view, our two drivers are complementary in terms of where their sweet spot is from a natural driving style."

The differences are marginal, but telling, and it's clear from Norris's reaction to the session that he knew he had to find more on his final flying lap in Q3 to head off the inevitable riposte from Piastri.

"My first [Q3] lap was pretty good," he said. "But there were places where I felt I could go quicker. Turn 2 wasn't one of them but I just caught a bit of understeer there."

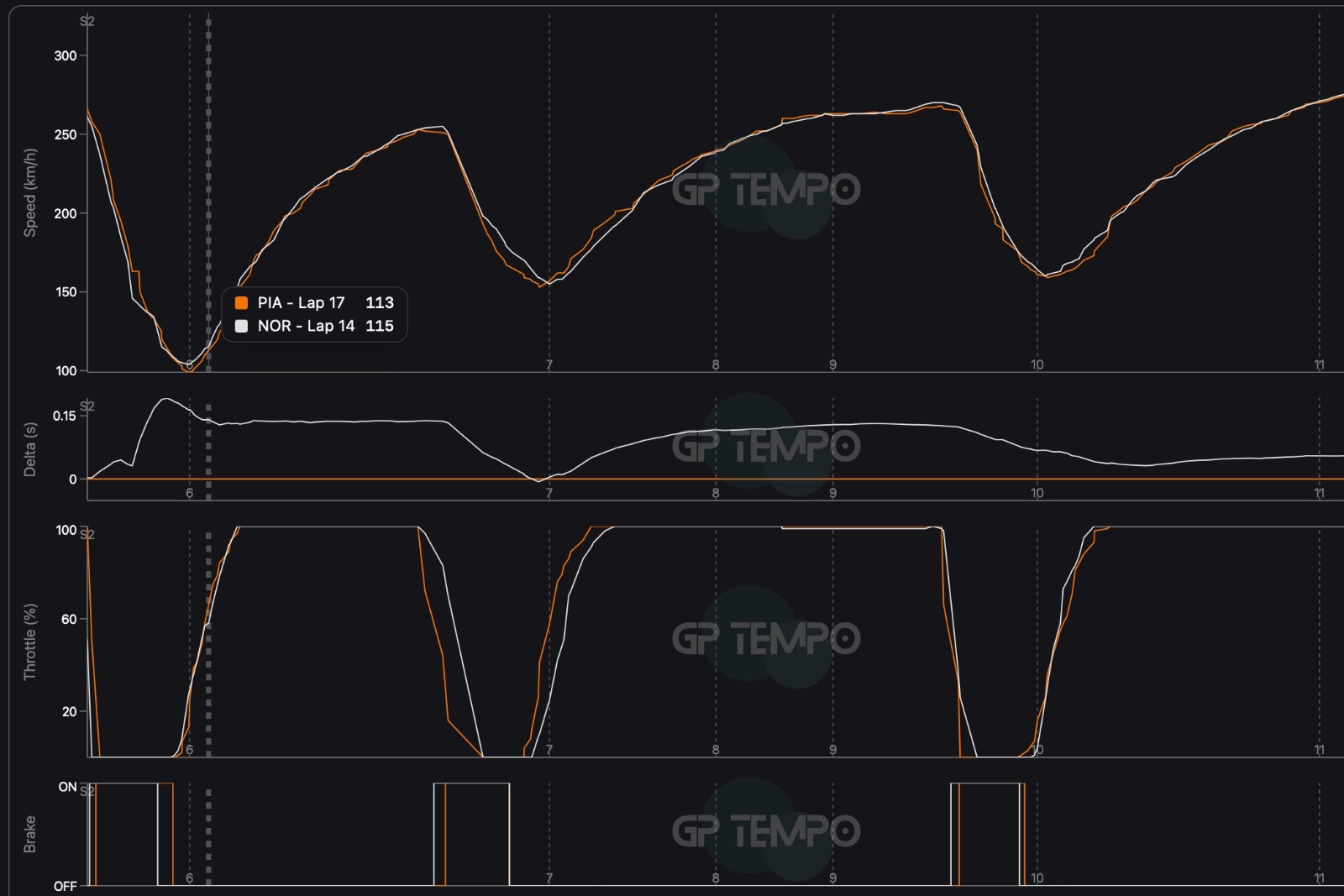

In the image above we've compared Piastri's final flying lap with Norris's aborted one. As you can see, both drivers began to get off the throttle for Turn 1 at the same time but Piastri (orange trace) did so more sharply, blending into the brake earlier.

Since it's a constant-radius corner, both drivers got on the throttle again before reaching the apex, but Piastri's application was initially more linear and decisive. Norris (white trace) took fractionally longer before committing fully.

Towards Turn 2, Norris moved well over to the right of the track to try to open the entry to the corner. Again, he was later off the throttle and on the brake, but also released the brake later.

At this point, coming to the apex of the corner, it was looking as if he was finding the milliseconds he needed, for he was travelling 6km/h quicker than his team-mate. But as the corner opened out he felt the understeer build and had to back right off the throttle – even then he rode very wide over the exit kerb. Knowing the lap was gone, he got out of it.

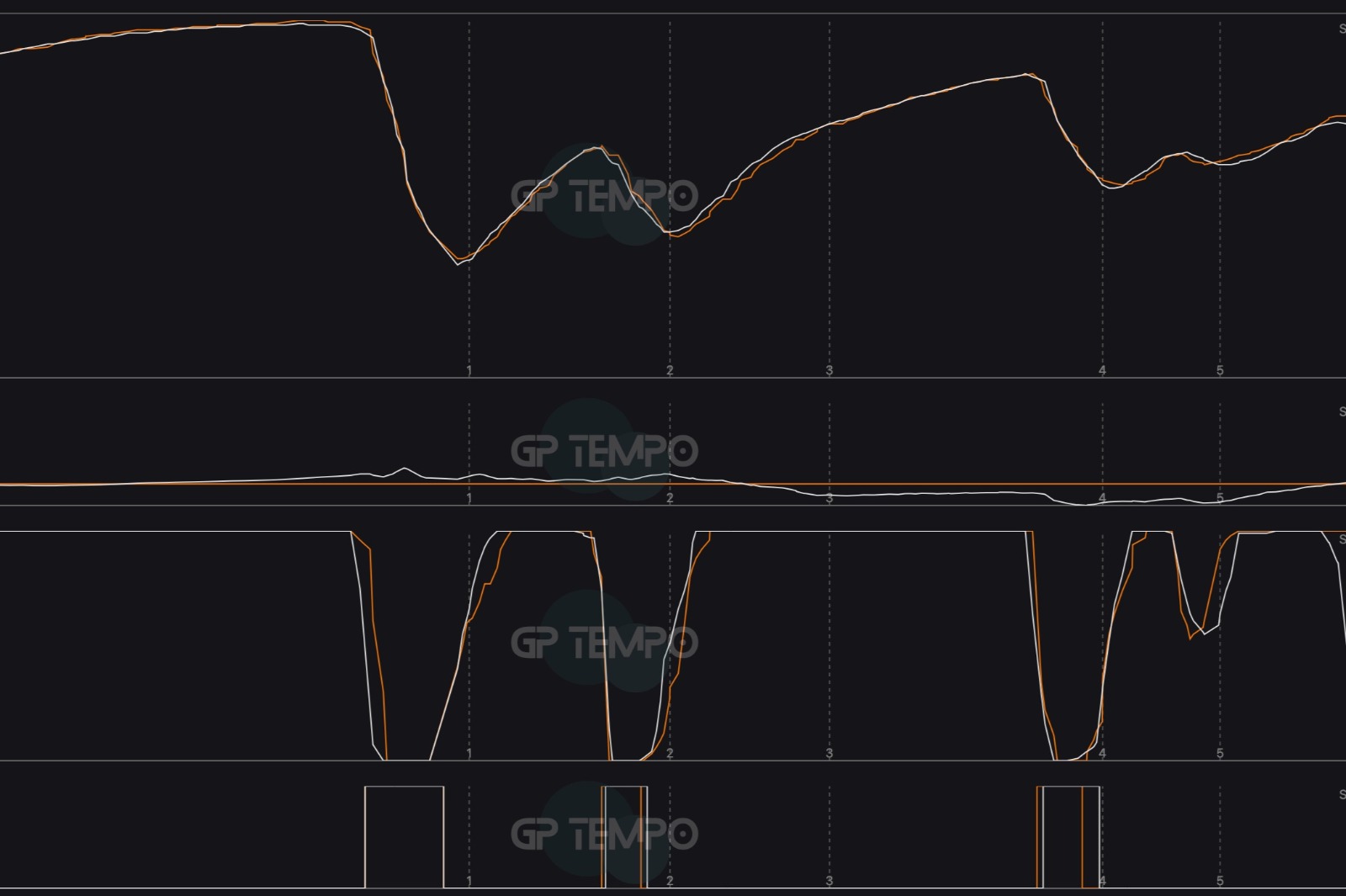

Comparing the first sector of Norris' first Q3 run with Piastri's pole lap (above) shows what the Brit meant when he alluded to feeling there were places other than Turn 2 where he could go quicker. Actually, he was fractionally faster than Piastri for some of this sector, taking a similar approach to the first two corners – earlier off the throttle for Turn 1, but more decisively on it through Turn 2.

Piastri was ahead by milliseconds at this point, but Norris carried fractionally more speed into the slower Turn 4, got on the throttle a little earlier for the short chute between Turns 4 and 5, enabling him to turn that deficit around into a fractional advantage.

It was towards the junction between the sectors where Piastri made key gains, staying fully on the throttle for longer on the approach to Turn 6, the slowest corner on the track. That enabled him to clock a faster time through sector one overall and begin to build the gap through the start of sector two, rotating the car more precisely towards the apex of Turn 6.

There is almost nothing to separate their approaches in the telemetry traces, it's just a case of Norris scrubbing off a fraction more speed through understeer on the initial turn-in phase.

That left Norris a tenth in arrears, a gap he eroded by being later off the throttle on the approach to Turn 7 – but Piastri was earlier on the throttle before the apex and opened the margin again.

Before the entry to Turn 10, Norris blended out of the throttle and into the brake more progressively than Piastri, then was able to pick up the throttle again slightly later but more sharply at the apex, enabling him to whittle the margin – but not enough, for while Piastri's final sector wasn't his quickest, it was enough to leave him 0.108s ahead of Norris in the final order.

Verstappen, meanwhile, went faster still in the first sector but then leaked time through understeer to finish third, 0.264s off Piastri.

"I think overall Oscar was generating lap time slightly more comfortably than Lando," said Stella.

"In terms of potential, Lando was as fast – but if anything, on this type of high-grip surface it was more for Lando to make some adaptations.

"When you have to push to find the last millisecond, it can make your driving slightly less natural and maybe more prone to make mistakes. Very, very small differences, but I think Lando knew Oscar would have some time in hand for the final attempt and wanted to find a few milliseconds."

"It is the coolest thing ever," said Piastri, "to push an F1 car around this track – and only your right foot deciding whether it's a corner or not a corner."

Read and post comments