The great drama of politics is that no one knows the outcome of an election until the votes are cast. But some things about elections are pretty easy to predict—such as Republicans attacking Democrats on crime. Yet Democrats seem to have no answer to the attacks being lobbed at them in the final weeks of the midterm campaign, just as they are only now awakening to the fact that it might be wise to have an economic message for voters.

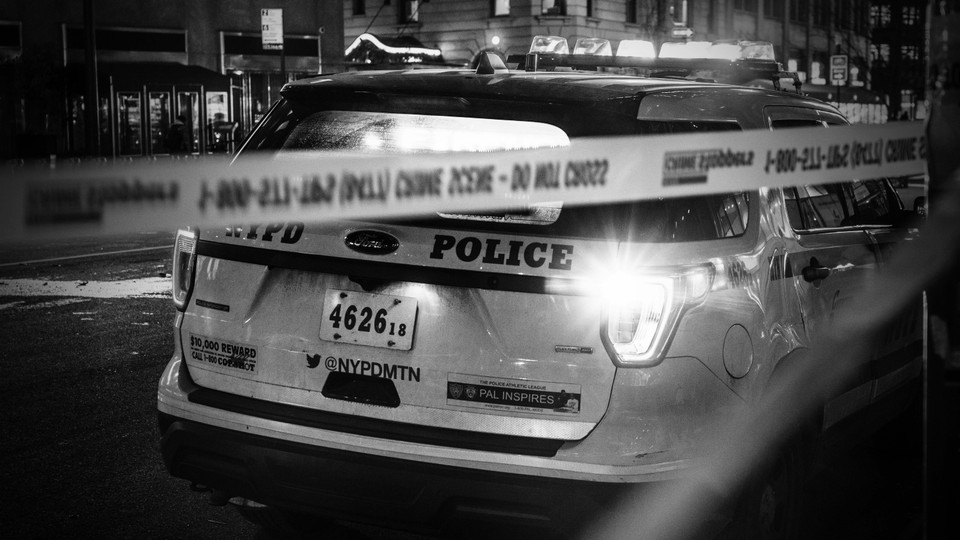

Crime is a devilish problem. Its causes are hard to understand and harder to influence. The trends run in long cycles, and although policy changes can alter the trends, they don’t do so quickly or simply. Expecting any candidate, or any party, to have a genuine answer to crime would be absurd. But crime is also politically potent, as Republicans grasp, and is thus fertile ground for attacks both fair and demagogic. (Just because you don’t have a simple, quick answer doesn’t mean you can’t claim you do.) In key races, Republicans have accused Democrats of being soft and ineffective on crime. They’ve attacked incumbents for presiding over rising violence and challengers for having supported cuts in police spending. In Illinois, the gubernatorial hopeful Darren Bailey even rented a Chicago apartment far from his farm as a way to spotlight crime.

The Democratic Party’s situation is tougher. The pollster Stan Greenberg has found that worry about rising crime under Democrats is a more potent fear than any other issue this cycle. As the party in power in Washington, it has to play defense. Any message has to satisfy swing voters and older Black voters worried about crime without alienating younger and more liberal voters who want changes to the justice system. The simplest answers are likely to undercut the party’s stated commitment to social justice and greater racial equality, and its conclusion that crime is best treated through root causes. The party is left without a message—much less an actual policy—that steers between being electorally disastrous and morally monstrous.

Because this is politics, facts matter, but they’re not always paramount. Still, the actual data are worth surveying. Violent crime, including murder, increased sharply in 2020, although property crime decreased. The situation in 2021 is much less clear. FBI data released in October show that violent crime was roughly flat last year (with a drop in robberies canceling out an increase in murders), but those numbers are not considered reliable, thanks to a change in the way the FBI gathers numbers that has left out statistics from many agencies. Preliminary data gathered by other organizations suggest a small decrease in murders and shootings in 2022, but also an uptick in property crimes.

Whatever the case, Americans are freaked out about crime. A Gallup poll released last week found that 78 percent of Americans say crime is increasing nationwide, matching the figure from 2020. (The all-time record, 89 percent, was set in 1992, when crime, in fact, hit its recorded high.) For the first time since 2016, a majority of Americans say they worry a “great deal” about crime. Less than a quarter are satisfied with crime policies—a 50 percent drop from 2020. More than seven in 10 say crime will be very or extremely important in their vote for Congress.

Democrats defending their record and critics of the criminal-justice system—two groups that have some overlap but also sharp disagreements—sometimes downplay crime and insist that people shouldn’t be so fearful. They correctly note that even after the 2020 spike, crime remains well below the worst levels of the late 1980s and early ’90s. They also correctly say that fears of crime are often driven more by the media and their bias for negative and lurid stories than by actual increases in crime.

Ideology drives coverage decisions too: The Washington Post finds that although all three of the big cable-news channels have been covering crime more in recent weeks, Fox News has far outpaced its rivals. One result is that views on crime are heavily polarized—Gallup’s finding that Americans see increased crime is driven largely by Republicans. Since 2020, the percentage of Republicans who say that crime has risen in the U.S. has increased from 85 percent to 95 percent. Over the same period, the percentage of Democrats who say the same has fallen from 74 percent to 61 percent, suggesting that ideology shapes their impression that crime is dropping.

The apologists also argue—once again, with good reason—that messaging around crime, whether in the press or from conservative politicians, is often rooted in appeals to racism. A recent, almost amusingly naive New York Times article reported, “As Republicans seize on crime as one of their leading issues in the final weeks of the midterm elections, they have deployed a series of attack lines, terms and imagery that have injected race into contests across the country.” Although the ads are worth noting, the phenomenon is hardly new. Richard Nixon used the threat of urban crime—that is to say, crime putatively committed by Black people—as a key campaign issue in 1968 and 1972. The George H. W. Bush strategist Lee Atwater infamously employed the case of William Horton to attack the Democratic nominee, Michael Dukakis, in 1988. And in 2016, Trump’s heavily racist immigration rhetoric focused squarely on crimes committed by unauthorized immigrants.

A staple of these attacks is a connection between urban areas and crime. Fear of crime drove white families out of cities and into suburbs starting in the mid-20th century, and once many white people left urban areas, politicians could easily yoke Black populations and violence together. Cities tend to have more consistent and easily accessed data, as well as more media attention, but violent crime has risen nearly as steeply in rural areas as in urban ones, The Wall Street Journal reported in June. During a gubernatorial debate in Oklahoma last month, the Democrat, Joy Hofmeister, drew jeers and dismissal for saying that the violent-crime rate in the Sooner State is higher than in California or New York, but she was right. (Perhaps it is no accident that Hofmeister is polling close to the Republican incumbent, Governor Kevin Stitt, in a deeply conservative state.)

Yet even if all of these rebuttals to concerns are true, crime really has jumped from the recent historic low. Besides, voters can’t simply be argued into giving up the way they feel, and few issues strike as directly at people as the fear that they or their loved ones might become victims of crime. In 2021, I reported that although Americans were concerned about rising crime nationwide, they tended to say that crime in their own neighborhoods remained about the same. Now, however, 56 percent of Americans tell Gallup that crime is up in their area—the highest since the pollster started measuring this sentiment, in 1972. (The violent-crime rate in 2020, the most recent year for which data are available, was almost 400 per 100,000 people; in 1992, it was roughly 760 per 100,000 people, but only 54 percent said crime was rising in their neighborhood.)

Individual Democrats have tried to find their own ways to talk about this. Representative Val Demings, who is running for the U.S. Senate in Florida, has drawn on her career as a police officer. But the Democratic Party writ large has not found a message. Stan Greenberg writes in The American Prospect that by the fall, the issue had become so dire that he advised candidates to not even bring it up: “To be honest, Democrats were in such terrible shape on crime at this late point, I said, speak as little as possible or mumble. Nothing they’ve said up until now was reassuring and helpful.”

In 2020, the challenge was that one portion of the party supported “defunding the police”—a vague phrase that encompassed everything from full-on abolition to experiments such as unarmed mental-health responders, and that was wildly unpopular with voters—while another, led by Joe Biden, did not. By this March, when President Biden used his State of the Union address to say, “Fund them. Fund them. Fund them,” the backlash within the Democratic Party was minimal.

Even with this intramural debate quieted, Democrats have no effective messaging to voters. In a letter to colleagues last week, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi offered some tips on how to talk about public safety, suggesting that candidates discuss the 2021 stimulus package and the 2022 spending bill, both of which provided money for local law enforcement. But those bills are arguably a Democratic liability overall, and bone-dry recitations of bills that people don’t view as having stopped crime from rising seem unlikely to have much effect. (Pelosi also said that Democrats should spotlight bills the House has passed to ban assault weapons and mandate safe gun storage. This might actually be popular—according to Gallup, no fear has risen more sharply over the past year than that of a child being harmed at school—but neither initiative has become law.)

This isn’t to rag on Pelosi in particular. Immediate solutions are in short supply. Scholars and police have no consensus on why crime declined so much from the 1990s until recently, and they have only provisional answers to why it’s started rising again. Many cities want to hire more police, but even when they have the funding to do so, recruits are in short supply. Reducing the number of guns on the streets would have a major effect, but it is politically impossible. Liberals tend to gravitate toward explanations for crime that focus on root causes, such as education and economic opportunity—but those are difficult and slow to fix, which makes them difficult to translate into pithy electoral slogans.

One example does exist of Democrats finding a way to win on crime: the 1992 election, when Bill Clinton emphasized crime by turning against core Democratic constituencies. (He famously accused the author and rapper Sister Souljah of being racist against white people.) It was extremely politically effective, and Clinton was able to win the presidency and grab back historically Democratic white voters who had defected to Ronald Reagan’s Republican Party.

Aping Clinton would be unlikely to work so well today. Many of those voters seem to be permanently lost to the Trump movement and white identity politics. Although Black voters tend to be generationally divided on crime and policing (older voters are more hawkish; younger ones are skeptical), the white voters who remain in the Democratic Party lean very liberal on social issues. Clinton also benefited from Democrats being out of power in 1992; two years later, voters rejected the party and ushered in the Republican Revolution.

More important, Clinton’s crime approach culminated in the 1994 crime bill, a massive piece of legislation that, although it contained some measures that were effective at fighting crime (such as the Violence Against Women Act and the assault-weapons ban), also included others that have not aged well. For example, the bill exacerbated racial disparities in drug sentencing and imposed lengthy mandatory-minimum sentences that took away judges’ and prosecutors’ discretion. By 2020, the law was anathema to the Democratic Party.

Returning to a simplistic tough-on-crime approach would be unconscionable today. One lesson of 2020, which is already being forgotten in some quarters, is how deeply flawed the criminal-justice system is. Simply giving it more resources and hoping for the best might produce a short-term drop in violent crime, but it would also be unsustainable and unjust, as the scholar Patrick Sharkey has argued.

Democrats won’t figure out how to square electoral imperatives on crime with moral ones in time for the 2022 election, and they will suffer for it at the polls. But the problem isn’t going away, so they’ll have plenty of opportunities to keep working at it.