Two kinds of deaths, one of ordinary people and the other of famous ones, periodically pose special challenges for the Chinese Communist Party. Both types can give rise to immediate vigils and later anniversary commemorations that become occasions for an outpouring of popular sentiment that turns from grief to anger—with sharp criticism of the authorities licensed by mourning.

The first kind involves incidents in which ordinary people die in a way that can be attributed to mistaken policies or official malfeasance. In 2008, after the Sichuan earthquake, for example, word that corruption had resulted in shoddy construction, leading to schools collapsing and children dying, generated widespread rage online.

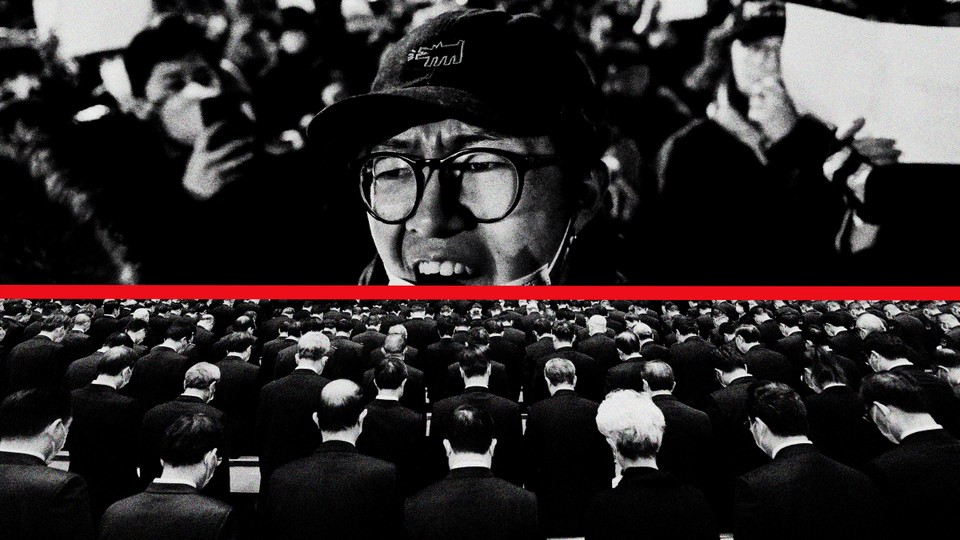

The other kind of death involves high-profile individuals whose demise may demand official mourning but may also turn into an occasion for popular protest. The most famous example of this came in 1989. The first stage in what turned into weeks of nationwide demonstrations, culminating in huge gatherings in Tiananmen Square and the June 4 massacre, took the form of a commemoration for Hu Yaobang, a former general secretary of the CCP.

Hu had been demoted from his top spot in the party hierarchy in 1987, after he was accused of taking too soft a line on student protests that had begun in late 1986. Because he was still a member of the politburo when he died, in April 1989, the CCP had to honor him but tried to keep the ceremonies low-key. Students seized the opportunity to wave banners, put up posters, and shout slogans about how the country would be better off if Hu had lived and more-conservative leaders had died instead.

For today’s CCP leaders, who are well aware of such precedents, the last week of November was a nervous one. This was because both kinds of death occurred in short order.

On November 24, a Thursday, at least 10 residents died in a building fire in Urumqi, a city in the Xinjiang region with a large Uyghur population. News of the deaths soon spread, and many reports blamed zero-COVID lockdown measures for hampering the efforts of residents trying to escape and firefighters trying to battle the blaze. Soon, weekend vigils for the victims were being held in cities across China, the first such widespread street gatherings in decades. These vigils morphed into protests as participants, infuriated by its clumsy and inhumane enforcement, demanded changes to the zero-COVID policy. The demonstrations in Urumqi itself, which had already been locked down for months, were replicated in Shanghai, which had endured an intense lockdown last spring, and in many other localities.

Some protesters moved on to mocking official censorship by holding up blank sheets of paper. Others quoted slogans calling for freedom and attacking dictatorship that had appeared on protest banners unfurled from a bridge in Beijing in October. Some even criticized Xi Jinping directly.

On November 30, news broke of the death, at age 96, of Jiang Zemin, a former general secretary of the CCP and president of the country—both titles now held by Xi Jinping (and by Hu Jintao before him). By then, the street actions related to the Urumqi fire had largely died down, though tensions over lockdowns remained. The authorities immediately took steps to preempt a second protest growing out of a new round of mourning. Censors got instructions to keep online discussion of Jiang’s death from veering in dangerous directions. The CCP also moved to quell any opportunity for unrest early in December, roughing up protesters to send one signal and announcing some concessions on the zero-COVID policy to send another.

The response of Xi and his allies to what Jiang’s death might bring may seem like an overreaction. Jiang’s status at the time of his death, which had more than once been rumored to have already happened, was that of a respected retired statesman and party elder, so he did not present a likely posthumous symbol for demonstrators. No public displays of protest-tinged mourning competed with the state ceremony over which Xi presided, but more subtle expressions of dissent did manifest. Some people went online to praise Jiang pointedly for qualities that Xi lacks, such as a willingness to give interviews to journalists (including foreign ones); others played on parallel nicknames for the two leaders, contrasting the affectionate “Grandpa Jiang,” which China’s internet censors have recently banned, with the officially promoted nickname “Grandpa Xi.” Even though Jiang rose to power at the time of the June 4 massacre, which he subsequently defended, some commentators on social media hailed his era as a halcyon time of prosperity and relative freedom—things that had gradually been lost under Hu, and even more so under Xi.

To place all of this in perspective, several recent precedents exist for what has happened since November 24. Most recent were the labor protests that erupted just before the Urumqi fire, in Zhengzhou at a giant factory that makes iPhones. A theme of the unrest was that the COVID measures designed to protect lives were sometimes endangering them: One of the labor conditions provoking discontent was that healthy workers could be confined in close quarters with ones who were sick. Though different from the vigils that came later in the month, social-media posts about the factory unrest gave people a prior sense that protest was in the air.

Going back a bit further, a bus crash on September 18 killed 27 people who were being removed from the city of Guiyang to a quarantine facility in another part of Guizhou province. That human tragedy led to a flurry of online criticism of the way the zero-COVID policy was being implemented. Some social-media posters noted that the crash took place on the anniversary of a 1931 invasion of Manchuria by Japanese troops, a trauma described in official histories as a “national humiliation” for pre-Communist China—a phrase now applied to the bus crash by social-media users as a comparable disgrace for Communist-ruled China.

Another event earlier in the pandemic—another notable death, in fact—prefigured the response to Jiang’s. This was the demise in early 2020 of Li Wenliang, a whistleblowing doctor widely admired for his efforts to spread the word about the dangers of COVID. At first, he was criticized by the CCP for spreading malicious “rumors,” but later—after he himself had died of the disease—the authorities shifted gears and extolled him as a patriotic, truth-telling martyr. Social-media users continue to mark the February anniversary of his death, referring to Li warmly as a dearly departed brother or uncle. Despite the CCP’s efforts to honor him, his memory is commonly celebrated with a degree of veiled, or even overt, criticism of the party dispensation.

One thing to watch for now is how much the apartment-building tragedy in Urumqi, which, notably, claimed the lives of Uyghur residents, affects discussions in China of the discrimination against such Turkic Muslim groups, including grave human-rights abuses, in Xinjiang. A recent New York Times opinion article by James Millward, a historian of the region, argues that it was “unusual and poignant” to see “Han Chinese protesting the deaths of Uyghurs.” He pointed out that “for years, the Chinese party-state” had “justified its Xinjiang policies by demonizing Uyghurs as terrorists and religious extremists, or at least as ignorant peasants in need of forceful ‘vocational training.’” The images “from the Urumqi fire,” he said, “humanized and normalized Uyghurs” for at least some Han Chinese living far from Xinjiang. Some of the slogans circulated online, he noted, used phrases such as “we are all Xinjiang people” and called the victims of the fire “compatriots.” To Millward, the vigils and protests offered a rare instance of solidarity across ethnic lines in China and an implicit rebuke to the official narrative of Uyghurs as potentially dangerous Islamists and terrorists.

We can also expect November 24 to have a place on the political calendar as another anniversary potentially marked with expressions of sorrow that may take on a political edge. The anniversaries of tragedies involving the deaths of ordinary citizens have proved in China even more potent than those commemorating famous figures. The June 4 massacre, in which both student protesters and Beijing residents of all ages and walks of life were among those killed, was one such trauma. Proof of that anniversary’s potency comes every year in the steps authorities take to prevent its being marked at all. Until recently, the way activists in Hong Kong observed the June 4 massacre offered a striking contrast with the absence of any commemoration on the mainland. Then, in 2020, Beijing tightened the screws there, too. Xi Jinping and his allies will have to hope that with a relaxation of the zero-COVID policy, the Chinese people will be less moved to outrage and not protest again when the anniversaries of Li’s death and the Urumqi fire come around next year.