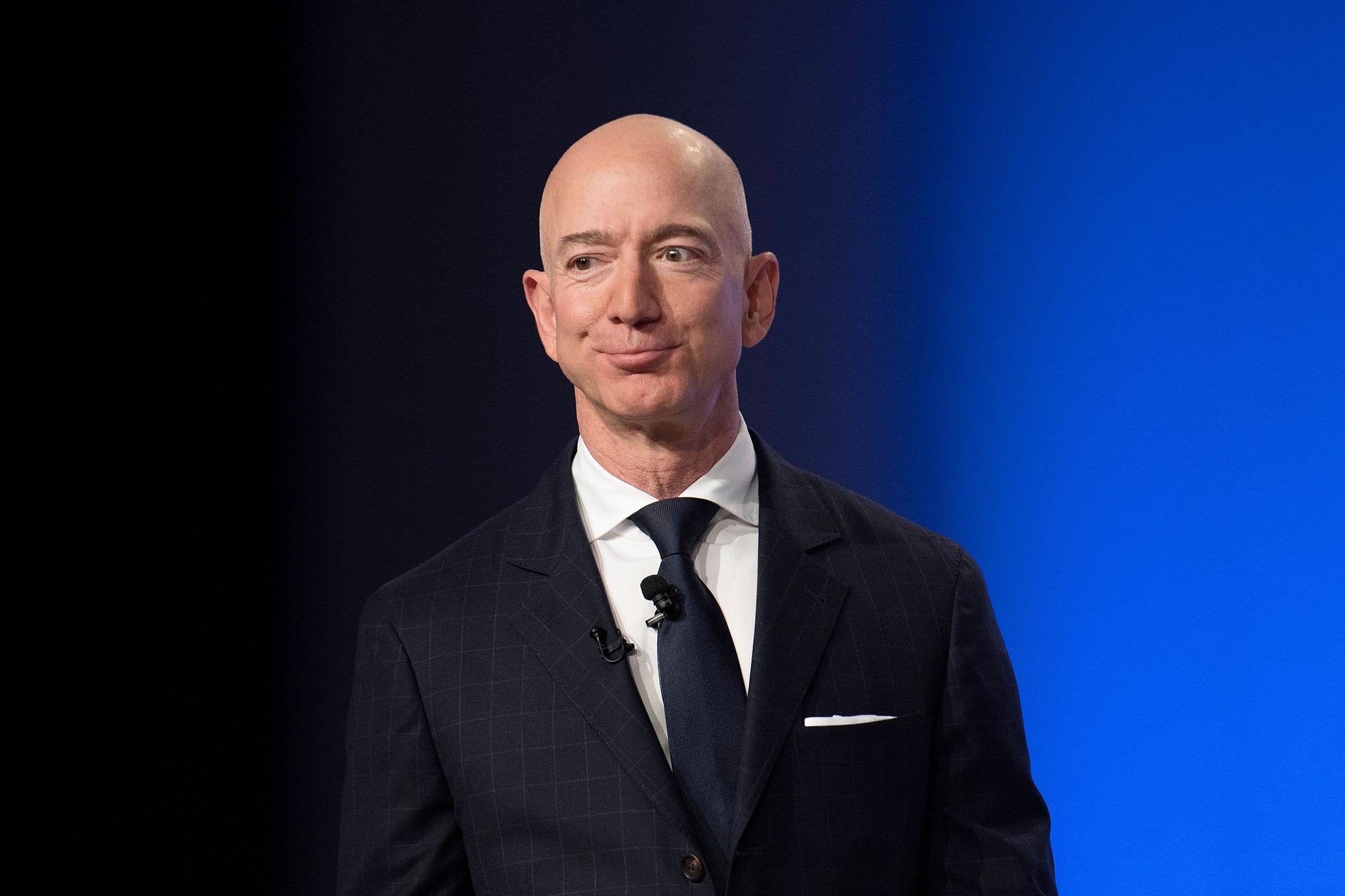

By the time it was announced last July that Jeff Bezos, currently the world’s third richest billionaire, had donated $200 million to the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum, the two parties had already hammered out how the money would be spent: $70 million would support renovation of the museum, while the remaining $130 million would be used to build a new education center on the National Mall in Washington, D.C.

Along with that financial directive, the written donor agreement between Bezos and the Smithsonian also stipulates what the new center will be named (the Bezos Learning Center), and for how long (at least 50 years), and exactly where Bezos’ name must be emblazoned (facing the National Mall, facing Independence Avenue, inside the museum), according to MarketWatch, which obtained the agreement through a public-records request.

“Totally typical, especially with larger gifts,” says Rebekah Beaulieu, editor of The State of Museums: Voices from the Field, noting that these are exactly the kind of details you would expect to find in an agreement involving a naming opportunity for an institution.

What may be less typical these days is that the donor agreement lacks a morals clause designed to protect the institution. In practical terms, the omission of a so-called “bad boy clause” may mean that in the event of any future scandal, the Smithsonian would not be able to remove Bezos’ name in the same way that, say, the Metropolitan Museum nixed the Sackler name from galleries due to controversy surrounding the family’s role in the opioid epidemic.

“When we're talking about a morals clause, we're talking about one form of a termination clause. These are very, very standard in museums,” says Beaulieu. “We have seen termination clauses really since the beginning of modern policy for museums, dating back to the late 19th and early 20th centuries. There are cases of moral clauses, in particular, being referenced as early as the 1950s.”

“What is new is that I would say over the past 10 to 15 years, such clauses are gaining more visibility, as we increasingly have expectations about where the money is coming from when gifts are made to museums,” Beaulieu continues. “So this is part of a larger movement, where we're kind of analyzing problematic history and problematic capitalism.” In the case of the Met and the Sacklers, for example, “that was something that came out of an ethical misalignment between the organization and where the money came from, Purdue Pharma.”

But the mere absence of a morals clause is not necessarily unusual. “I'm not actually surprised by that,” says Joanne Florino, the Adam Meyerson fellow at Philanthropy Roundtable. “The Smithsonian has, I think, taken an interesting perspective on a lot of these things,” she said, noting that the National Museum of Asian Art still has a gallery bearing the Sackler name. “I'm not drawing any parallels between Jeff Bezos and the Sacklers. I know people get angry with Mr. Bezos, primarily because he's wealthy. But there's really nothing to indicate that there would be a need for moral qualms.”

It would also be wrong to assume that the founder of Amazon and Blue Origin refused to have a morals clause, says Florino. “We don't know if that clause was even brought up. It's equally likely that the Smithsonian never even brought up that issue.”

Florino’s instincts are spot on. “We do not have a morals clause in any gift agreements or contracts,” confirms Linda St. Thomas, spokesperson for the Smithsonian. “If a situation arises, we have a review process to evaluate the situation. But there is no such clause in our agreements with any donor.”

In granting Bezos a half-century of naming rights, it appears that the Smithsonian did bend a policy for the billionaire. In 2011, the Smithsonian enacted the 20-year policy to “get away from perpetuity” in gift agreements, a spokeswoman told MarketWatch.

“He didn't ask for perpetuity,” says Florino. “He asked for a specific timeframe, apparently. I don't see anything unusual about that.”

Besides, the Smithsonian is unlikely to have a cookie-cutter template for donor agreements. “It's absolutely individualized, especially at that level,” says Beaulieu.

There is also an alignment between the organization and donor to consider. Beyond the sheer enormity of the donation—the $200 million gift is the largest to the Smithsonian since the institution’s founding in 1846—there is a sense that Bezos’ launching the new education center is a heart-on-his-sleeve passion project and a reflection of his lifelong fascination with space, culminating in his own trip to the final frontier.

“The Smithsonian plays a vital role in igniting the imaginations of our future builders and dreamers,” Bezos said in a July statement. “Every child is born with great potential, and it’s inspiration that unlocks that potential. My love affair with science, invention and space did that for me, and I hope this gift does that for others.”

Having given more than $2 billion over his lifetime to various good causes, Bezos landed on Forbes’ list of 25 Most Philanthropic Billionaires 2022. In particular, he has cultivated a special relationship with the Smithsonian over the past decade. He and his ex-wife, MacKenzie Scott, were founding donors to the National Museum of African American History and Culture, and in return, the Smithsonian has honored Bezos with a number of honors, including the American Ingenuity Award for Technology in 2016 and a Portrait of a Nation Prize in 2019. He was also a featured speaker at the National Air and Space Museum for the 2016 John H. Glenn Lecture in Space History.

Still, philanthropy experts note that there’s a growing chorus in the public who question the relationships between big donors and institutions. “I think that anyone who's a billionaire, who's made his or her money through the free market system, is likely to get attacked simply for the way they made their money,” says Florino.