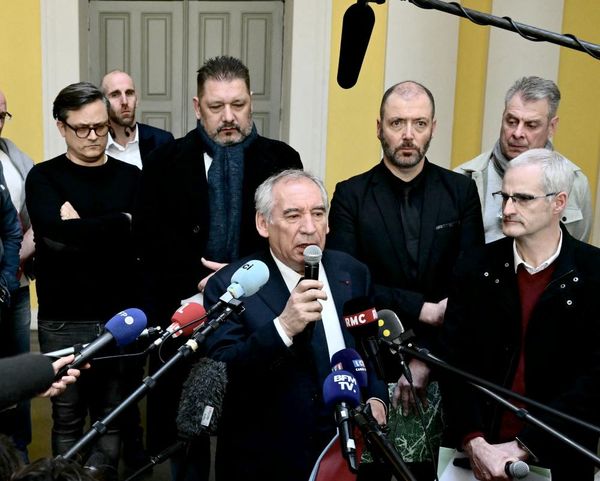

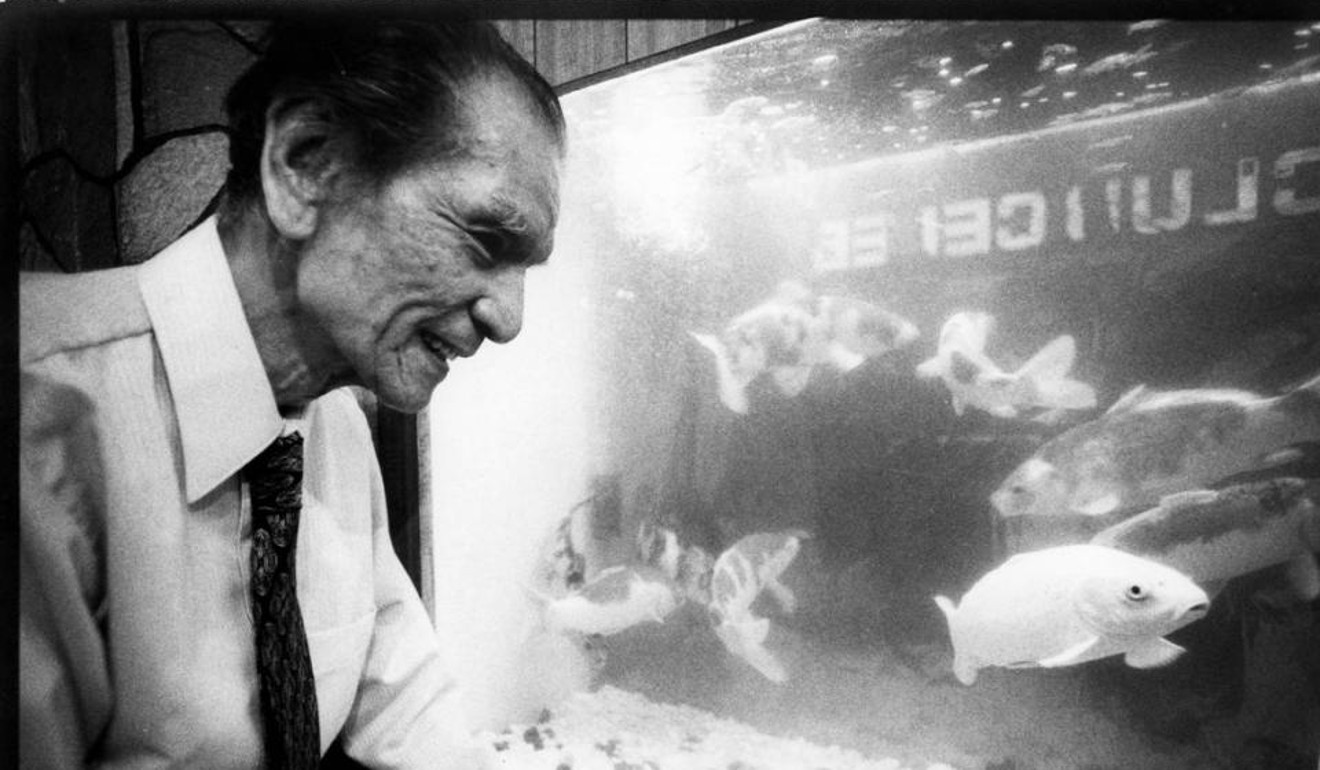

Last month, a major exhibition featuring more than 100 of the late Luis Chan Fook-sin’s works opened at the Power Station of Art museum in Shanghai, an expanded version of a major survey of his work shown in the city in 2012 and of another retrospective at the Zhi Art Museum in Chengdu, western China, last year.

That the work of Chan, a Hong Kong visual artist, is popular in China is unusual, since the former British colony usually occupies the margins of the country’s mainstream cultural narrative. Many people in China still think of Hong Kong as a cultural desert – an inaccurate 20th century label that’s stuck – and the city’s still recent union with the country makes its own art history a disparate appendage to the broader China story.

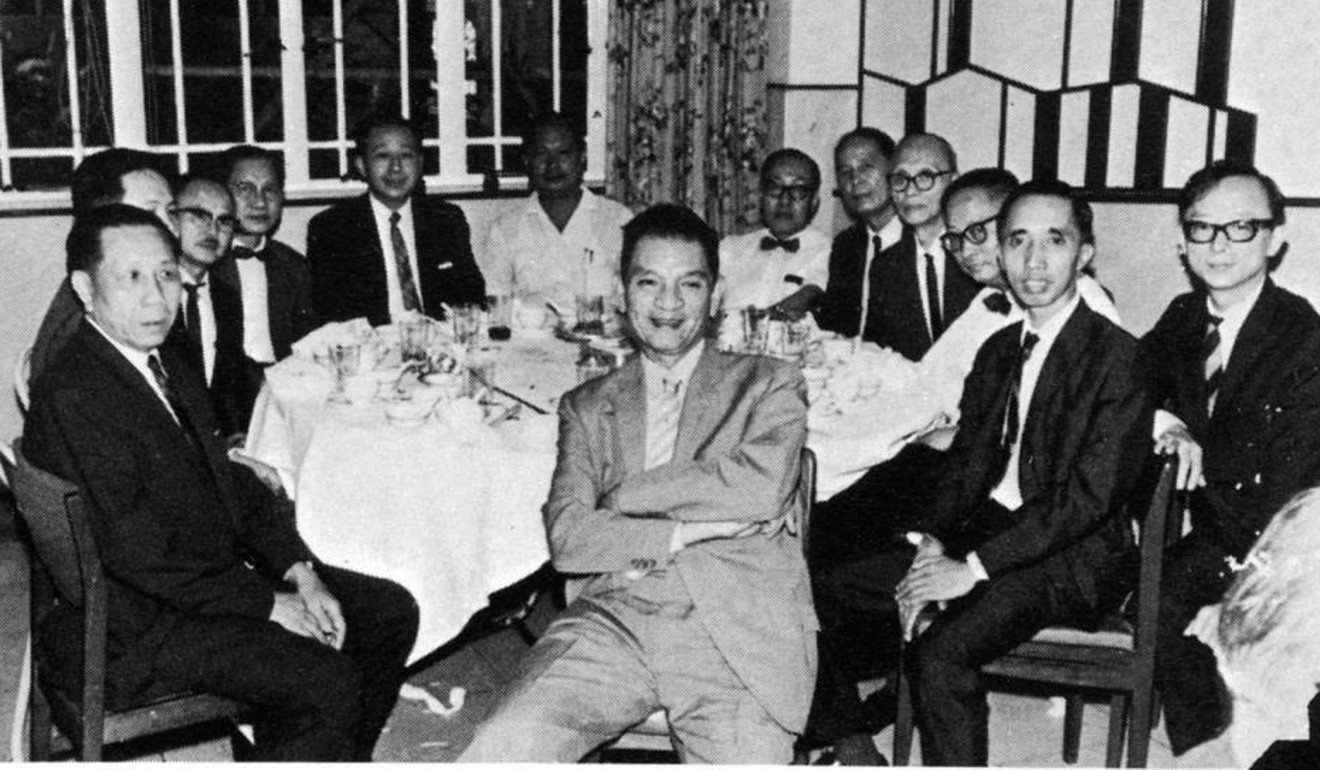

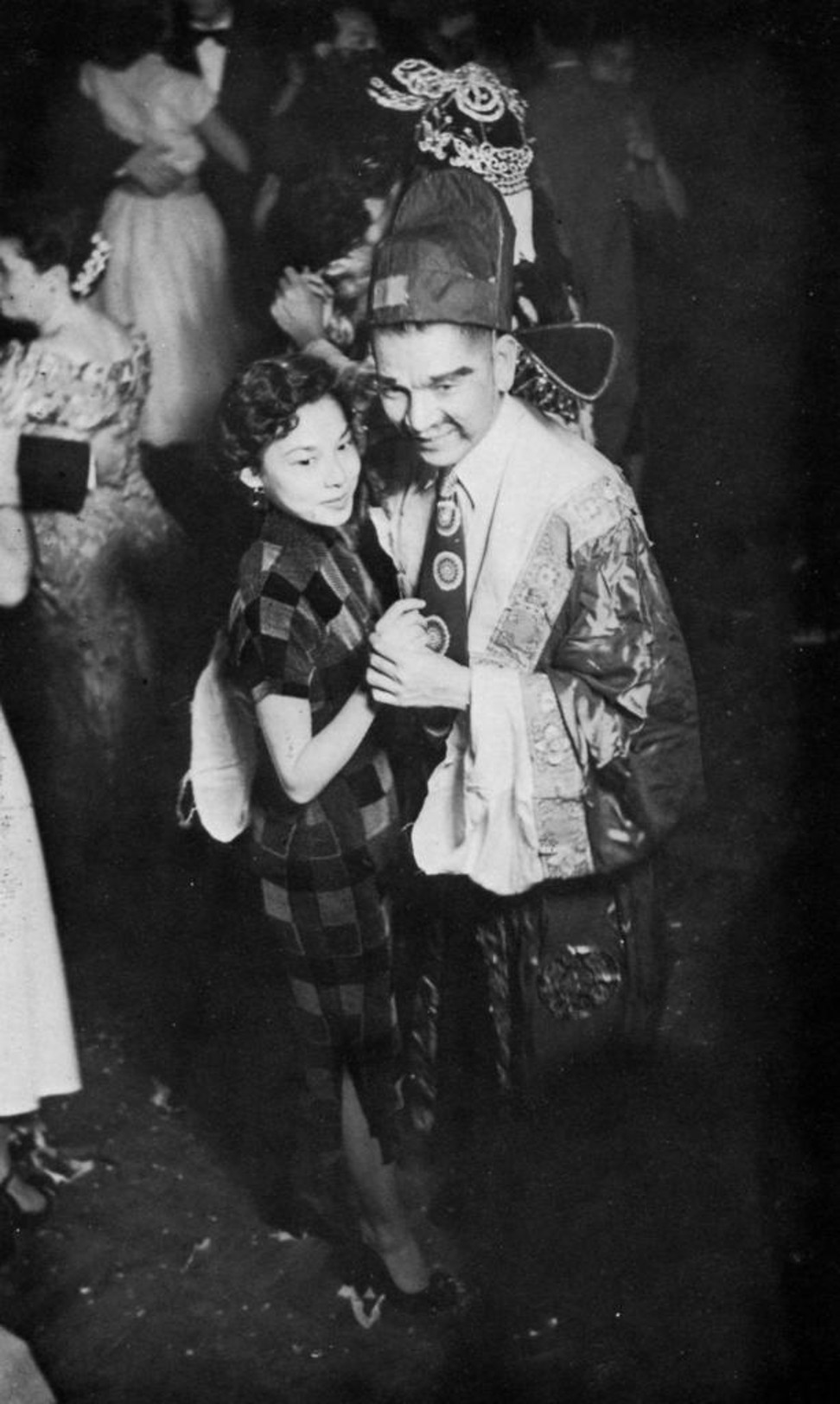

After all, late 20th century Hong Kong artists lived in a totally different world from their peers to the north; the party-loving Chan, who worked as an artist while China was still in the grips of the devastating Cultural Revolution, exemplified that.

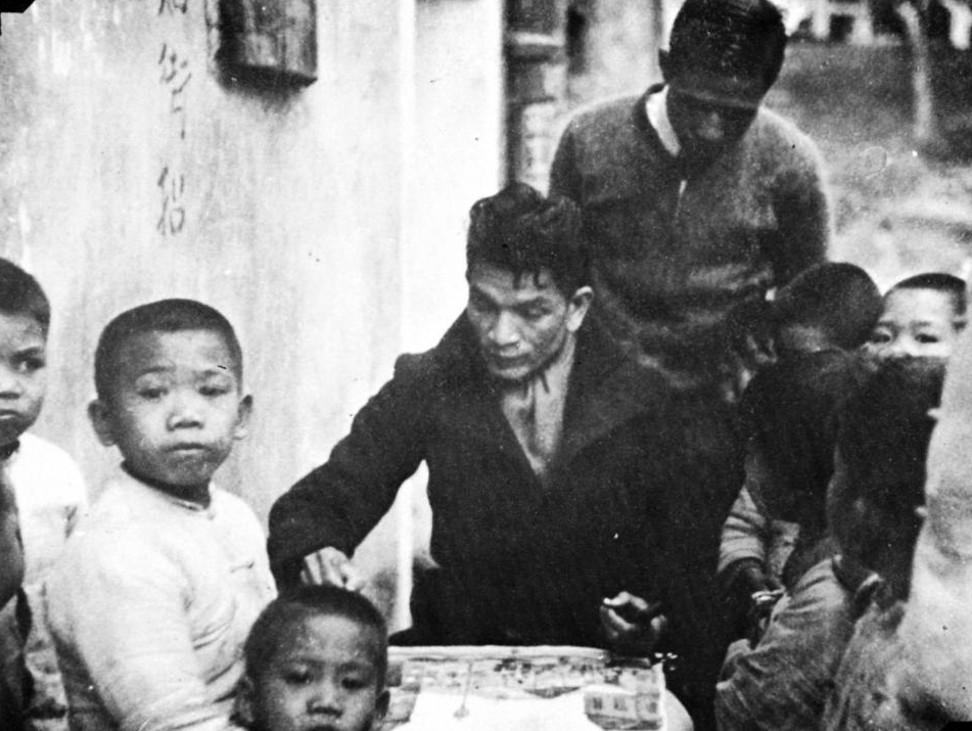

The self-taught artist had no training in traditional Chinese ink painting or calligraphy. Born in Panama, his family moved to Hong Kong in 1910 when he was five.

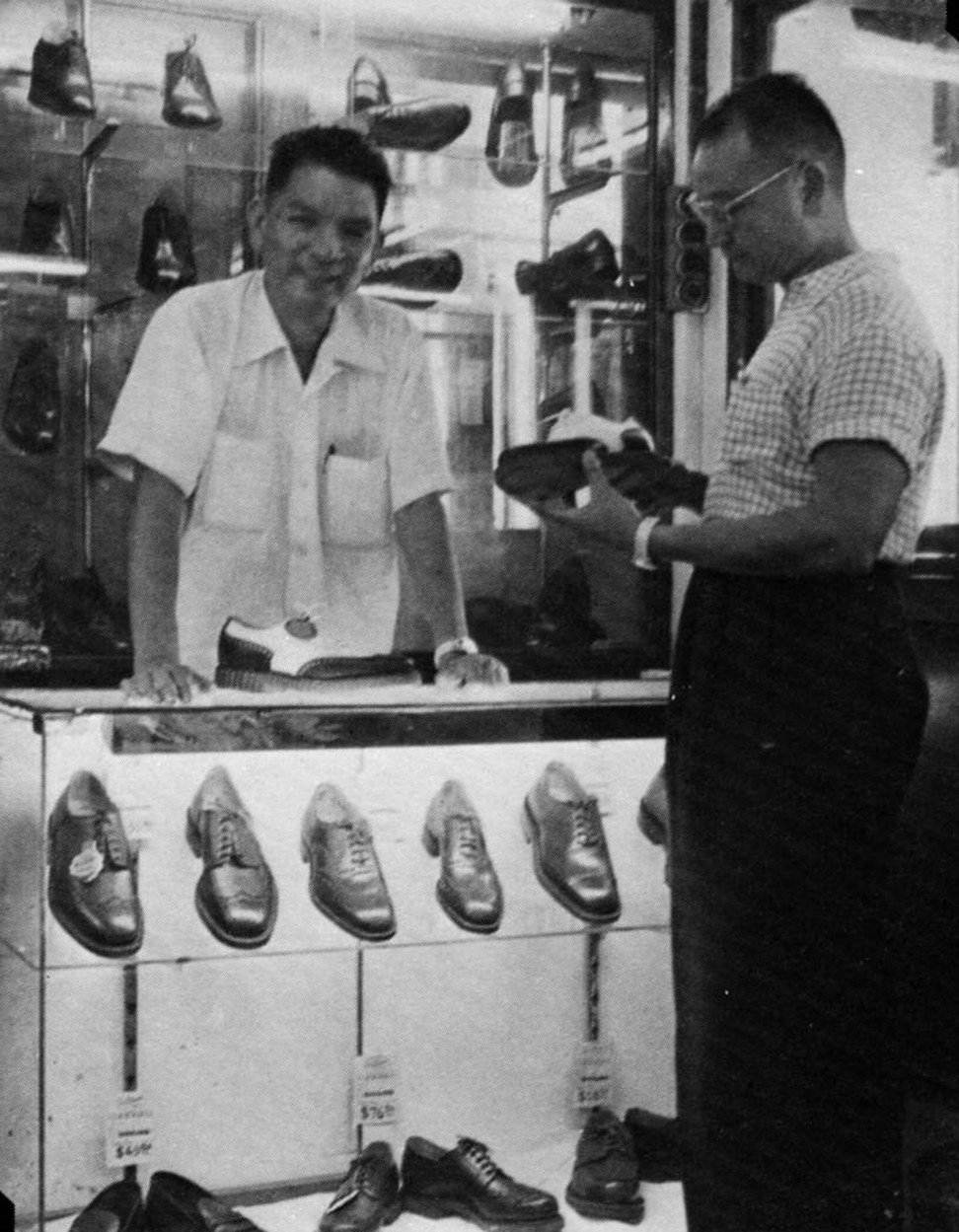

The teenage Chan’s first artistic passion was designing typefaces – he told gallerist Johnson Chang Tsong-zung in 1984 that he was inspired by the 1920s font of the South China Morning Post. While he had a variety of day jobs – from legal clerk to a business selling Savile Row shoes – he took correspondence art courses and became so adept at painting Western-style landscapes he became known as the “Watercolour King”.

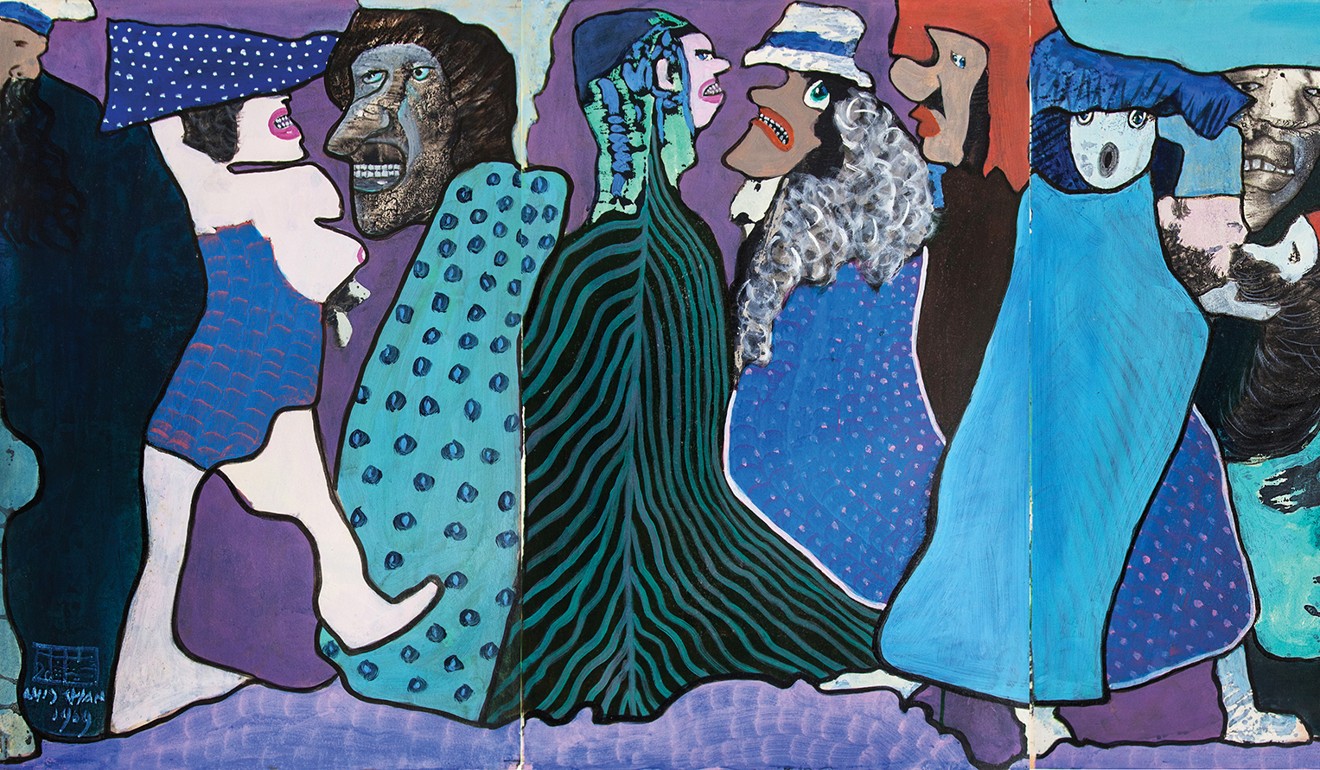

Later, he tried more experimental styles and techniques such as cubism, Surrealism, collages and spray painting, but only temporarily. By the late 1970s, he had found a way of depicting Hong Kong, the mongrel of a city that was his home, through fantastical monsters, absurd caricatures, or strange, abstract compositions that spoke only to himself.

Shen Kuiyi, an art historian at the University of California San Diego who curated the Shanghai exhibition, said he first came across Chan’s paintings in 1995 at the Hong Kong Arts Centre.

“There were just two of his works in the exhibition but I thought, wow, this is nothing like anything I’d seen before. Like another Hong Kong artist, Deng Fen, Chan was not a product of mainstream art movements and had found his own distinct voice,” he says.

He says there is a lot of interest in sorting through and conducting in-depth research into 20th century art in China, and he thinks that Hong Kong’s art history is a core part of that, even though its artists were describing a place so different from China then.

“Chan was a typical representative of Hong Kong. His life and art spanned the entire 20th century and coincided with Hong Kong’s transformation socially and developmentally. As the city became modern, international and cosmopolitan, he bid goodbye to realism and experimented,” says Shen.

“Then, in the 1970s, as Hong Kong was maturing into a big city, he found his own style. Unlike mainland [Chinese] artists of the era, such as Lin Fengmian and Xu Beihong, he never studied abroad and didn’t become part of a school of art. The reason he was representative of Hong Kong was because he stood for the city’s incredible diversity,” he said.

How does any of this relate to audiences in Shanghai today? Shen says the city is receptive to Chan’s works because the modern history of that city is also one of colliding cultures.

“And Chan made art about Hong Kong as it moved towards becoming a major cosmopolitan centre. Now Shanghai is going through the same process, and so the local audience see something of themselves when they look at Chan’s art.

“There is also a familiarity born of the two cities’ long and special ties. After all, there are so many Shanghainese families that moved to Hong Kong decades ago,” he says.

PSA Collection Series: Luis Chan, Power Station of Art, 200 Huayuangang Road, Huangpu District, Shanghai, Tue-Sun, 11am-7pm. Until June 23.