The name of Walter Bonatti first came to my attention when hiking the Tour du Mont Blanc, a 103 mile (165km) loop of the Mont Blanc massif that’s also the route of the famous UTMB. On a picturesque hillside, to the southeast of the mighty Grandes Jorasses, we found our lodgings for the night - Rifugio Bonatti, an endlessly charming alpine hut. It was easily my favorite hut we stayed at, perhaps because of its stunning location but possibly for the wealth of interesting images from mountaineering history on its wall.

If I’m honest, I don’t remember if I found out that much about Bonatti at that point. But in the years that followed I started devouring mountain literature at a fevered pace and stumbled across The Mountains of My Life, a collection of Bonatti’s writings, translated into English by Robert Marshall. The book revealed a remarkable career in the mountains, one that’s virtually peerless. He is, simply, one of the greatest mountaineers the Earth has ever seen.

From his heroic role in the first ascent of K2 to his staggering solo efforts in the Alps and the first ascent of Gasherbrum IV, Bonatti continually raised the bar, showing the world what was possible in the high mountains. His legacy, in mountaineering terms, is unsurpassed. It’s no wonder that he was the first ever recipient of the Piolet d’Or Lifetime Achievement Award, pretty much the highest accolade in mountaineering circles. Not only this, the award was henceforth named in his honor.

Here, I’ll attempt to do Bonatti justice in short-form, revealing the ascents that etched his name into mountaineering folklore and elevated his status into the upper echelons of the alpinist elite.

A prodigious talent

Bonatti was born in 1930, in Bergamo, a small city near Milan in the shadow of the Italian Prealps. A talented gymnast in his youth, at 18 he started using his physical prowess to climb on Grigna, a rocky mountain above Lake Como. He’d moved to Monza for work and fell in with colleagues who rock climbed in their spare time.

He forged a strong climbing partnership with co-worker Andrea Oggioni and it wouldn’t be long before the pair were measuring themselves against the toughest recorded climbs in the Alps on routes like the Cassin Route on the Walker Spur of the Grandes Jorasses.

Alongside Luciano Ghgo, he climbed the vertical East Face of the Grand Capucin, a staggering obelisk on the Mont Blanc massif. His star was shining bright, so when Italian mountaineering stalwart Ardito Desio began forming a team to take on the first ascent of the world’s second highest mountain, Bonatti would be an obvious choice.

The first ascent of K2

Bonatti’s high-altitude career began with a climb that would become a controversial epic and drastically alter the course of his life, as well as his standing among Italian mountaineers. Aged 24, Bonatti was one of the strongest climbers on the Italian 1954 exepdition to K2 and he was eager to be on the first ascent team.

Before the final summit push, his role was to deliver oxygen cylinders to Lino Lacedelli and Achile Compagnoni at Camp IX, the highest camp at around 26,574ft (8,100m), which he did. However, according to Bonatti, Lacedelli and Compagnoni purposefully moved the camp higher up. Bonatti’s Hunza companion Amir Mehdi was struggling by this stage, thus giving Bonatti no chance of joining them for the summit.

Bonatti and Mehdi were forced into an unplanned bivouac, without even a sleeping bag, high up in the Death Zone. Both survived, though Mahdi lost his toes. After they’d begun their descent, Lacedelli and Compagnoni returned to collect the oxygen and then completed their summit push. Compagnoni, who ran out of oxygen later in the day, even accused Bonatti of using some of it up. Bonatti’s version of events was largely ignored by the climbing community and he was ostracized by some.

Many believe Bonatti would have had the skill and determination to achieve the summit without oxygen and that Lacadelli and Compagnoni's actions were designed to stop the talented young alpinist from outdoing their own achievement. The whole affair affected him greatly.

He wrote in The Mountains of My Life: ‘Until the conquest of K2, I had always felt a great affinity and trust for other men, but after what happened in 1954 I came to mistrust people’. His version of events was eventually accepted in 2007 by the Italian Alpine Club, more than 50 years after the climb.

Staggering ascents

The Bonatti Pillar on the Aiguille du Dru, a breathtaking dagger of granite on the Mont Blanc massif, is the stuff of legend. For many years, the route was a benchmark for other elite alpinists to follow – that is, until the route collapsed in 2005.

In 1955, a year after the K2 ascent, Bonatti had figuratively etched his name into the mountain with his staggeringly bold, solo, six-day ascent. A masterpiece of alpinism, it was the climb that propelled Bonatti’s name into the general public’s consciousness, in Italy and France in particular, as mountaineering's rising global star.

In the years that followed, he continued to raise the bar in both the Alps and on expeditions to the Andes and Karakorum. He made alpine first ascents on the Grand Pilier d’Angle – the East Face with Toni Gobbi in 1957 and the icy North Face in 1962 with Cosimo Zappelli – as well as on the Red Pillar on Mont Blanc’s immense Brouillard Face in 1959 with Oggioni.

Between these were visits to South America. First, was Patagonia in 1958 to attempt the unclimbed Cerro Torre, an iconic spear of granite to the west of the Fitz Roy massif, one of the world's most beautiful mountains. However, he and compatriot Carlo Mauri found the climb to be too difficult.

It’s thought that the knowledge and equipment of the time would mean that anyone would have failed to scale the peak. It would be another 16 years before the first ascent, achieved in 1974 by Italians Daniele Chiappa, Mario Conti, Casimiro Ferrari and Pino Negri.

Gasherbrum IV

In the heart of the mighty Karakorum, rising high above the Baltoro glacier, is Gasherbrum IV, the world’s 17th highest mountain. In 1958, it was still unclimbed and represented a glittering prize for the alpine elite. Bonatti was naturally first choice for an Italian expedition to the peak that year, led by the great Ricardo Cassin.

In mid-July, Bonatti and his great climbing partner Mauri fought their way up towards the summit ridge, battling technical climbing over a series of gendarmes, the like of which had perhaps never been seen at such altitude. However, they were forced into a retreat by the arrival of the monsoon. After a rest at Base Camp, the expedition gained pace once more, this time with knowledge of what awaited above.

On the August 6, Bonatti and Mauri tackled the pinnacled crest of the summit ridge, arriving triumphant at a staggeringly exposed summit. However, there was no way of knowing if this first summit was the higher of Gashbrum IV’s two, so they wearily continued along the ridge to the second. As it turned out, the first was the higher, but the plucky Italian pair weren’t to know. With time running low, they braced against savage winds during the descent, glad to arrive at the relative safety of Camp 5, before descending to Base Camp.

The scale of Bonatti and Mauri’s achievement is perhaps best underlined by the fact that no one would stand on the summit again for 28 years, until 1986 when American mountaineers Greg Child, Tom Hargis and Australian Tim Macartney-Snape managed to ascend the Northwest Ridge. To this day, the mountain is considered as the most difficult sub-26247ft (8,000m) peak in the Greater Ranges.

Tragedies and a change of direction

Bonatti encountered the bitter taste of tragedy during Christmas 1956 when difficult conditions disrupted an attempt on the Pear Route on Mont Blanc’s Brenva side. He and partner Silvano Gheser switched to the more technically straightforward Brenva Spur, where Frenchman Jean Vincendon and Belgian François Henry were climbing.

A storm arrived and the four teamed up in what was now a battle for survival, making it to the Brenva col where a decision awaited: descend to Chamonix via hazardous terrain, or continue on to Mont Blanc’s summit, a technically easier task but much more physically demanding. Bonatti and Gheser pushed on for Mont Blanc and eventual safety – though Gheser lost fingers to frostbite. Meanwhile, Vincendon and Henry eventually turned back to make for Chamonix. The pair became pinned down in a crevasse and, despite rescue efforts, died of exposure to the cold.

However, the events on the Central Pillar of Freney in 1961 were to leave an even bigger mark on Bonatti. A gargantuan monolith on Mont Blanc’s Italian side, the Central Pillar was one of the last great unclimbed challenges left in the Alps. Bonatti, alongside his favorite climbing partner Andrea Oggioni and a paying client, Roberto Gallieni, were approaching the objective and decided to join forces with a four-strong French team and all climb together.

Just 328ft (100m) from the top of the climb, the seven climbers became trapped by an unexpected summer snowstorm that lasted for days. Bonatti took the reins, realizing the deadly situation they’d found themselves in and directed the team to an improvised descent, though the odds were totally stacked against them.

Two of the French team died of exhaustion, as did Bonatti’s friend Oggioni. Within reach of the safety of the Gamba Hut, another member of the French team, Pierre Kohlmann, died of a heart attack. Bonatti arrived at the hut and was described by the rescue team’s medic as being ‘beyond any chance of survival’. Yet, survive he did, along with his client Gallieni and the sole French survivor Pierre Mazeaud. It’s thought that none would have survived the ordeal had it not been for Bonatti’s leadership.

Also in 1961, he released Le Mie Montagne, now thought to be the most widely-read mountaineering book of all time. It cemented his place as a household name and he’d continue to climb to an exceptionally high standard over the coming years, notably pulling off the first winter ascent of the Walker Spur on the Grandes Jorasses, with Michel Vaucher.

However, after the death of Oggioni, and well aware of the dangers of the kind of climbs he was undertaking, Bonatti started to eye up a different kind of existence. His relationships were suffering and it’s thought he was getting less satisfaction out of his daring ascents. So, in 1965, at the age of 35, Bonatti set about achieving one last great climb…

The North Face of the Matterhorn

Bonatti retired from high-stakes alpinism with a characteristic flourish, pulling off the first ever solo winter ascent of the North Face of the Matterhorn. It took him five days to scale the immense face to the breathlessly exposed summit. The North Face Direct route is one that sees few repetitions and it remains a challenge for even the greatest mountaineers. With the help of modern equipment and techniques, Swiss legend Ueli Steck managed the feat in 25 hours back in 2006.

Personal life and accolades

Following the controversy of K2’s first ascent and his subsequent successes, Bonatti has both enjoyed and endured a rollercoaster ride when it comes to public recognition. History would put his name on the right side of the K2 debacle and, in his prime, he was a bona fide celebrity in Italy, enjoying almost movie star status.

After the Matterhorn, he’d go on to travel the world extensively on far flung adventures, writing for Italian magazine Epocha. As a child, he’d dreamed not only of mountaineering adventures, but of expeditions to jungles and deserts around the globe. His status and talent for storytelling allowed him to live out this dream. Whether it was visiting remote tribes in New Guinea or exploring the source of the Amazon in South America, he became a fully-fledged adventure journalist. He still climbed, mostly in the Alps, but this was on his own terms and in private. He had nothing left to prove to anyone.

A self-proclaimed ‘loner’ for much of his life, Bonatti found love in 1980, when he met former actress Rossana Podestà. The two were together until his death from pancreatic cancer in 2011.

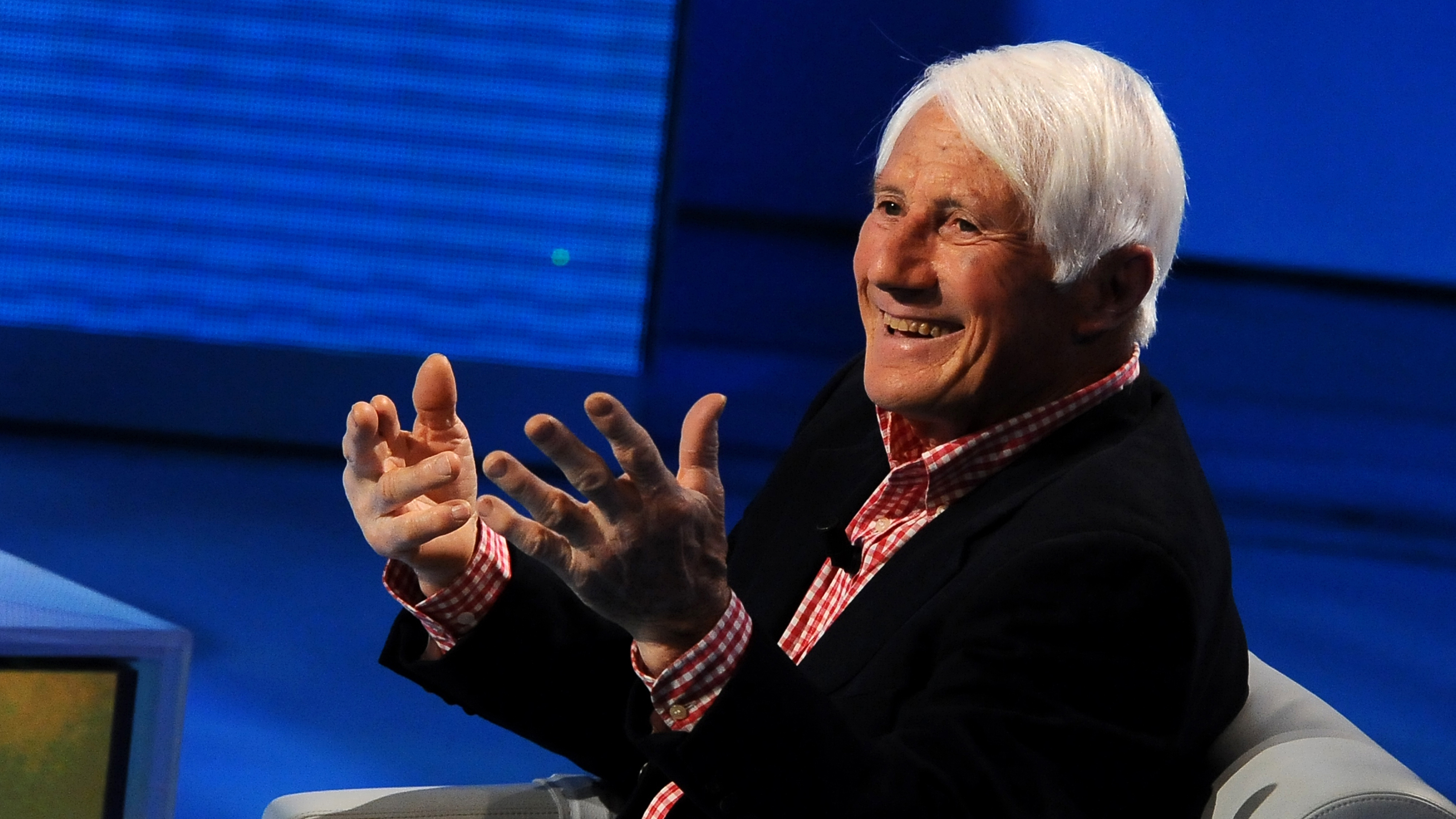

In 2009, Bonatti was presented with the ultimate honor – the first ever Piolet d’Or Lifetime Achievement Award. Not only this, but the then-new award was also named after him, a huge show of respect from the world’s mountaineering community. The Walter Bonatti Award has since been presented to some of the greatest adventurers of our time, such as Reinhold Messner, British mountaineering legend Chris Bonington and Catherine Destivelle.