If last year’s Jaguar debacle taught us anything – other than the fact that Miami Pink really divides opinion – it’s that a wholesale brand reinvention should never be taken lightly. And that it’s only an option when the brand in question is failing to support the wider business ambition.

What we see from the likes of Jaguar, Aberdeen (formerly abrdn) and Royal Mail (formerly, famously briefly, Consignia) are examples of brands carelessly dumping their heritage – and feeling the heat as a result.

For the most part, brands under pressure to modernise are better advised to think about revitalisation rather than reinvention (ie. refreshes vs rebrands) – going back to their brand origins to make themselves relevant again, and holding onto their equity, rather than dumping it. Doing this preserves hard-won brand equity that takes years to build up and that can be extremely valuable.

Where wholesale brand transformation can go awry

Big brand changes can be dangerous. Think back to the early 2000s, when Tropicana famously did away with its existing packaging. The pack changed so much that consumers couldn’t recognise it on the shelf; sales plummeted as a result, and a more familiar pack was quickly reinstated.

Then we have Royal Mail rebranding to Consignia, again in the early 2000s. People didn’t understand the reason for the change; it was widely ridiculed and a quick U-turn from management followed.

Two takeaways: first, denying or distancing yourself from your heritage makes people suspicious. It implies, in some way, that there’s something wrong with your past.

Second, brand codes and associations take years to earn – Tropicana’s were playing a valuable role in helping consumers locate it on the shelf, Royal Mail’s were equally powerful. And in doing away with its brand, it underestimated the power of its rich heritage.

Then you have a more recent example: abrdn, which came under fire for appearing to try too hard to modernise (it recently reneged on its controversial name change). At the time, there was a feeling that the rebrand was something of a fig leaf to cover underlying business issues, with one commentator telling The Guardian the rebrand was "ill thought-out” and the new name "could be pronounced 'a burden'".

Striking the balance between reinvention and revolution

It’s absolutely possible to reinvent yourself as a brand without losing your heritage. Mini and Lucozade are two such examples: in 2015, Mini reinvented itself as a fun, adventurous car brand – global but with British roots. But it kept hold of its most valuable brand codes: its name, the Mini dashboard, its proportions and the brand’s cheeky spirit.

Lucozade, for many years associated with being ill (or at least overcoming illness), hitched a ride on the energy drinks train and found a new audience with a younger generation. Its reinvention saw it sidestep into an emerging category while keeping hold of its essence and heritage.

There are many ways in which brands can rejuvenate themselves – on a smaller scale:

Carlsberg, a famously green brand, turned itself red – temporarily – to celebrate its sponsorship of Liverpool. Its green code being so firmly established in the culture that it could confidently play with the colour.

Cadbury’s Dairy milk regularly plays with its long-established brand codes to keep its brand fresh and lively.

When is it okay to part with your past?

I’d suggest two situations when a complete, throw the baby out with the bathwater reinvention is needed.

1. In cases of extreme emergency

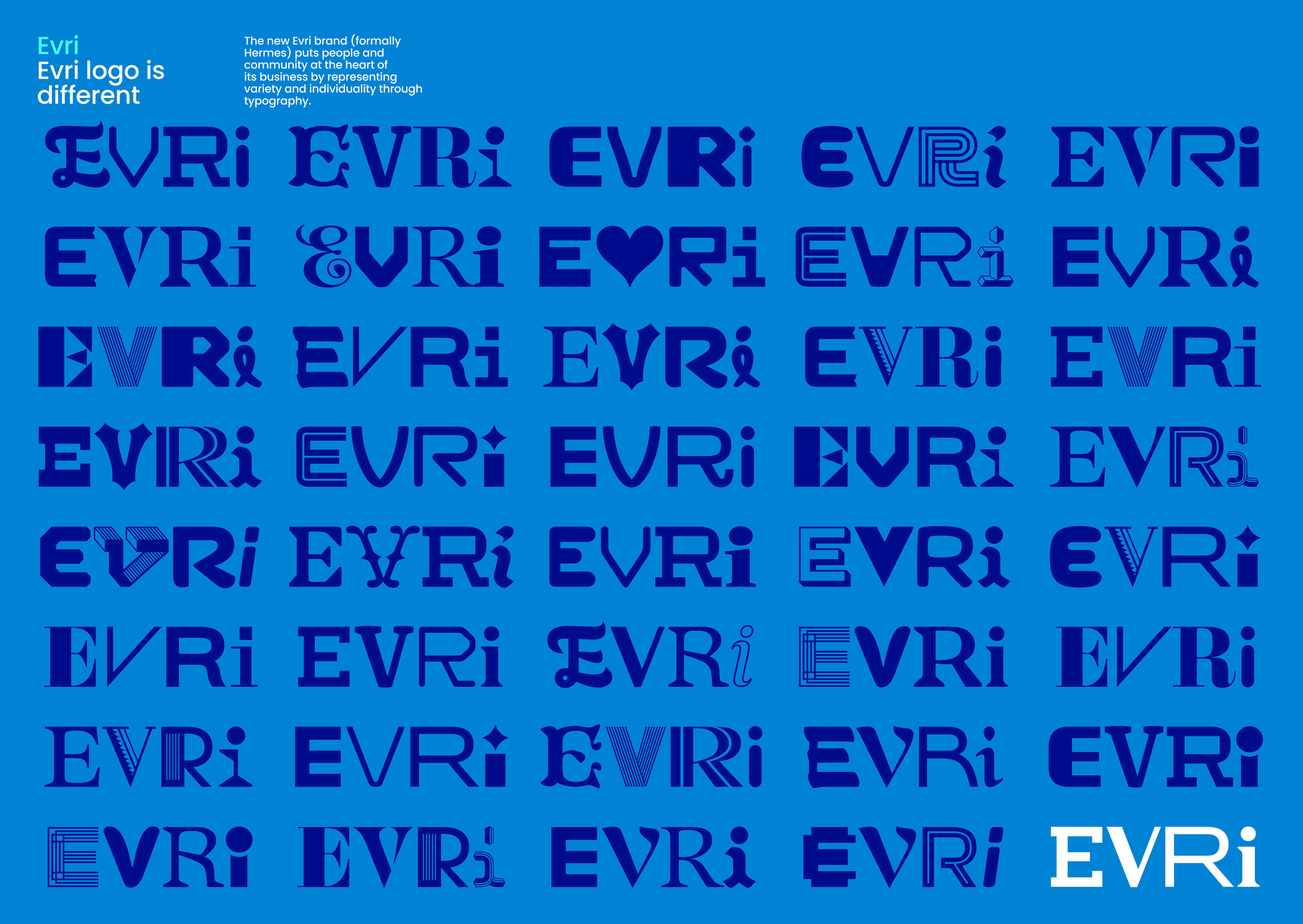

If your brand’s heritage has become overwhelmingly negative and is dragging the business down, it might be time for a rebrand. A recent example of this would be Hermes rebranding to Evri in 2022 – this followed hot on the heels of a damning 2021 Times investigation, which concluded that Hermes was the UK’s ‘worst’ courier.

2. When there’s been a shift in business ambition and strategy

The other scenario when it’s worth parting with your heritage is when you’ve changed as a brand and become something different. National Express Group rebranding to Mobico Group is a great example. The new brand prompted a re-appraisal – internally and externally – and spurred the company onwards.

Other examples include Spotify modifying its positioning to include podcasts as well as music, and Lululemon rebranding itself as a holistic wellness (rather than fitness wear) brand.

Taking all this into account, Jaguar’s 2024 rebrand remains baffling. In terms of brand equity, it was guilty of forgetting to check the rearview mirrors; it disowned 100 years of heritage and seemed to either want to distance itself from a negative past or conclude that nothing in the past held value for their future direction. For a brand with such a rich and storied heritage, this felt like a risky move.

The takeaway for brand leaders? If you’re thinking of making a clean break with your past, think carefully before you do so.