There are those who say that one or other of the McLaren drivers should have the 2025 Formula 1 world championship in the bag by now.

Within that group it has been claimed that Oscar Piastri's peculiar off-weekend in Azerbaijan – shunting in qualifying, getting the start wrong, then crashing on the opening lap – is evidence of the Australian 'bottling it'.

But, there is many a slip twixt cup and lip in F1. While you can count the number of times Emerson Fittipaldi crashed on the fingers of one hand, some of the greatest drivers of the past century have had embarrassing and occasionally injurious moments - even the great Jim Clark.

Here are some examples...

Juan Manuel Fangio - 1952 Monza Grand Prix

The greatest driver of his era came within a whisker of only being world champion once. In 1952, when European race organisers responded to the shortage of competitive F1 cars by excluding them from championship races, Juan Manuel Fangio committed to a mixed programme of events for BRM and Maserati.

When the Italian marque announced it would have its new A6GCM F2 cars ready for the non-championship Monza Grand Prix on Sunday 8 June, it left the maestro in a pickle. He had already committed to race BRM’s temperamental Type 15 in the Ulster Trophy Formula Libre race at Dundrod road course near Lisburn in Northern Ireland. But he had also given his word to Maserati’s owner Adolfo Orsi that he would race his new car.

Fangio’s engine blew up after he made a spirited recovery from a spin at the infamous Lindsay Hairpin (witnessed by this writer’s eventual father-in-law). Prince Bira had promised to fly Fangio to Milan in his own plane but seemed to have forgotten this arrangement, and had already departed after crashing out on the opening lap.

Bad weather then left Fangio with no option but to fly to Paris and drive the rest of the way, borrowing a car from Louis Rosier for the purpose. Driving throughout the night, slapping himself in the face to stay awake, Fangio arrived at Monza with half an hour to spare and, as guest star, was allowed to start from the back of the grid in a new Maserati which had been reserved for him.

In his biography Fangio claimed to have had a shower, swallowed some aspirins, and then driven like the proverbial clappers, passing six cars on the opening lap. On the second time around he misjudged his trajectory through the second Lesmo, hit the apex kerb and went wide at the exit, where he struck a straw bale which had been baked solid in the summer sun.

The ensuing somersault was so violent that, while Fangio was thrown clear, his shoes were later found in the mangled wreck. Fangio was hospitalised for weeks with a broken neck. Early visitors to his bedside, 1951 champion Giuseppe Farina and Andre Simon, hardened racers both, retreated from the room in shock at this appearance.

Having made a remarkable recovery, Fangio promised himself never again to race while fatigued.

Alberto Ascari - 1955 Monaco Grand Prix

A deeply superstitious man, Alberto Ascari never raced on the 26th of the month – that was the day he lost his father in a racing accident – and would make an immediate u-turn if he saw a black cat in his vicinity. For all these eccentricities, though, Ascari was an unflappable perfectionist once ensconced in the cockpit, an exemplar of precision and consistency in an era when many of the fastest drivers took every corner at the ragged edge.

Disputes with Enzo Ferrari over money led Ascari to dissolve his relationship with the Scuderia, at least at grand prix level, but committing to Lancia’s new F1 project meant the double world champion was an absentee from top-level racing for much of 1954. While technically adventurous - its engine acted as a partially stressed element of the chassis - the short-wheelbase D50 was twitchy and taming it meant the car arrived very late that year.

Ascari was one of several drivers to wilt in the Argentine summer heat in the January 1955 season opener in Buenos Aires, crashing out on the 21st lap. But it was his mishap in the next round, four months later, which was more spectacular.

In Monaco the Mercedes cars of Fangio and Stirling Moss were running 1-2, as was customary, but when Fangio’s car halted with a broken driveshaft at half distance and then Moss’s engine blew with 20 of the 100 laps to go, Ascari was in the lead. It’s said that a group of the drivers had taken a stroll around the circuit that morning and, as they reached the chicane, one had gestured at the inner apex and said, “Whoever touches here, goes in the water.” Ascari had scurried away in search of a wooden object to touch.

Moss had been within half a minute or so of lapping Ascari when his engine let go, so the Italian had no idea he was now in the lead as he made his way down through the hairpin, into the tunnel and out again. There would have been no signals warning of oil from Moss’s Mercedes. Some believe Ascari could have been distracted by cheers from the crowd, who had been informed of the development by the trackside commentator.

The actual cause remains an object of speculation. But, at the chicane, the paragon of precision and consistency lost control and speared over the balustrade, into the harbour, breaking his nose in the process. “At least I can swim,” he’s said to have told Fangio later.

Jim Clark - 1965 Race of Champions

It is extraordinary to imagine a driver of Clark’s gifts making an error – if he did, his peerless car control was sure to swiftly catch and correct it before the human eye could discern it – and yet there is one documented example of him blundering during his pomp. 1965 was the year he won the world championship and the Indy 500, but he also had a clumsy-looking shunt in the non-championship Race of Champions at Brands Hatch.

Clark won the first heat after a spirited dice with Dan Gurney’s Brabham in the usual damp conditions one would expect of mid-March in the garden of England. In the second he was duking it out with Gurney once more when he slid wide at what is now known as Graham Hill Bend, putting a wheel on the grass before smiting an earth bank. Clark’s team-mate Mike Spence, third in the first heat, came through to win.

Later Clark would claim via his regular column in the Daily Telegraph that he had been driving well within himself to get a read on how well Gurney’s Goodyears compared with his Dunlops in the slippery conditions, but still couldn’t understand why the accident happened.

Jack Brabham - 1970 Monaco Grand Prix

For all that ‘Black Jack’ Brabham brought an edgy and aggressive style born from his formative experiences racing ‘Midget’ cars on dirt, he rarely met the scenery. Even a dramatic off early in his grand prix career, Portugal 1959, came as a consequence of lapping a wayward backmarker.

Jack always blamed mobile chicane Mario de Araujo Cabral for the shunt which involved him somersaulting into a trackside telegraph pole and being thrown from his car into the path of Cooper team-mate Masten Gregory. His only other serious accidents during his frontline racing career came as a consequence of tyre failures.

Brabham had hoped to retire at the end of 1969 and have Jochen Rindt as his lead driver, but Rindt - guided by manager Bernie Eccclestone - succumbed to the temptation of more money and what was likely a faster car at Lotus. As it panned out, the new Lotus 72’s anti-dive, anti-squat suspension geometry was an ill-sorted mess in the 1970 season opener while Jack’s new BT33, engineer Ron Tauranac’s first monocoque, was handily quick.

In Monaco a disgruntled Rindt reverted to the ageing 49C and was in an unmotivated funk all weekend, even kicking an overly officious policeman who demanded to see his pass on the way to the grid. That all changed in the closing laps of the race as he found himself in second place with Brabham up front.

With three laps to go, Brabham was badly baulked on the run up the hill by Jo Siffert, who was weaving to cure a fuel-feed problem and paying inadequate attention to his mirrors. Now Jack could see Jochen in his mirrors - and what an unnerving sight the newly remotivated Rindt must have been, even to a three-time world champion. The Lotus was now on the giddy edge of adhesion as its driver closed in.

On the last lap, with the final corner approaching, Brabham had to lap Piers Courage’s limping De Tomaso and his trajectory took him off the racing line. His left-front wheel locked up first, then the other, and he slid into the barrier.

Some kind soul has uploaded footage of the final lap onto YouTube, where you can witness those final moments – including Rindt’s disbelieving shake of the head as he passes the scene to inherit the win.

Jody Scheckter - 1973 British Grand Prix

Six years later he would be crowned world champion but, in 1973, Jody Scheckter was an altogether rawer talent. His performances in a McLaren in Formula 2 led to a handful of appearances in a third McLaren in grands prix, and it was during the fourth of these, only his second championship outing in the new M23, that he attained a degree of infamy which would dog him for several seasons.

Scheckter qualified sixth - team-mates Denny Hulme and Peter Revson were second and third. The South African rookie made a great start to annex fourth and was impetuously challenging Hulme around the outside at Woodcote when he spun, rebounding off the outside barrier back across the track.

As a consequence the multi-car accident increased in magnitude as those behind took evasive action. By the time the dust settled, nine cars had been eliminated and the race was red-flagged.

McLaren team manager Phil Kerr then had to smuggle Scheckter out of the circuit to avoid a furious John Surtees, who had lost all three of his works cars in the accident.

Ayrton Senna - 1988 Monaco Grand Prix

We’ll overlook Ayrton Senna’s mishap in Dallas in 1984 because, famously, it was the wall which moved. At Monaco in 1988 Senna delivered the qualifying lap to end of all qualifying laps, seemingly entering a fugue state.

“I was already on pole and I was going faster and faster,” he would say later. “One lap after the other – quicker, and quicker, and quicker.

“I was at one stage just on pole, then by half a second, and then one second. And I kept going. Suddenly, I was nearly two seconds faster than anybody else, including my team-mate with the same car. And I suddenly realized that I was no longer driving the car consciously.”

It is a moment which lives in F1’s collective mythology even though there is, sadly, no TV footage of it. Just as extraordinary were the events of the following day, where Senna swept away from the field and commanded the race with imperious hauteur – right up until the moment team boss Ron Dennis radioed him to slow down.

With fewer than 12 laps to go, Senna enjoyed a lead of nearly a minute to team-mate Alain Prost but had begun to push again, to Dennis’s chagrin. At Portier Senna slewed into the outside barrier and took both left-hand wheels off; frustrated, he stalked back to his apartment and stewed.

The TV coverage was once again wanting so no footage exists of the crash, but Senna later admitted that he had lost concentration and rhythm after the instruction to slow down, clipping the inside barrier.

Alain Prost - 1991 San Marino Grand Prix

In hindsight this was the beginning of the end of the professor’s relationship with the Scuderia. Despite Prost’s podium finish in the 1991 season opener at the unloved Phoenix street circuit, Ferrari’s 642 quickly proved to be a dud – to the extent that it would be replaced by an extensively reworked car mid-season.

Even this does not explain Prost’s peculiar exit from the San Marino Grand Prix, where on the formation lap he slithered off the wet track on the right-hand kink leading up to the Rivazza corner. McLaren’s Gerhard Berger also went over the grass but managed to rejoin, while Prost beached and stalled while facing the wrong way, failing to make the start.

Despite his status as a three-time world champion, he would be fired before season’s end, returning only after a season’s hiatus to claim his fourth crown in a Williams in 1993.

Mika Hakkinen - 1999 Italian Grand Prix

If the second of Mika Hakkinen’s world championships seems as inevitable as the first when viewed through the rose-tinted prism of hindsight, it was anything but – despite his nemesis Michael Schumacher being absent for much of the second half of the season after breaking his leg at Silverstone.

Michael’s team-mate Eddie Irvine pulled himself into title contention with a strong showing in Austria, followed by a gifted win (from stand-in team-mate Mika Salo) at Hockenheim. Hakkinen, in contrast, seemed discombobulated as his lead evaporated – not helped by his own team-mate, David Coulthard, nerfing him out of the way to win at Spa.

They arrived at Monza with Mika on 60 points and Eddie on 59 - these were the days, you see, before points were distributed like wedding confetti. Hakkinen set pole ahead of Heinz-Harald Frentzen’s Mugen-powered Jordan, and now it was Irvine’s turn to stamp his feet in frustration as he qualified eighth, over a second off Hakkinen’s pole time.

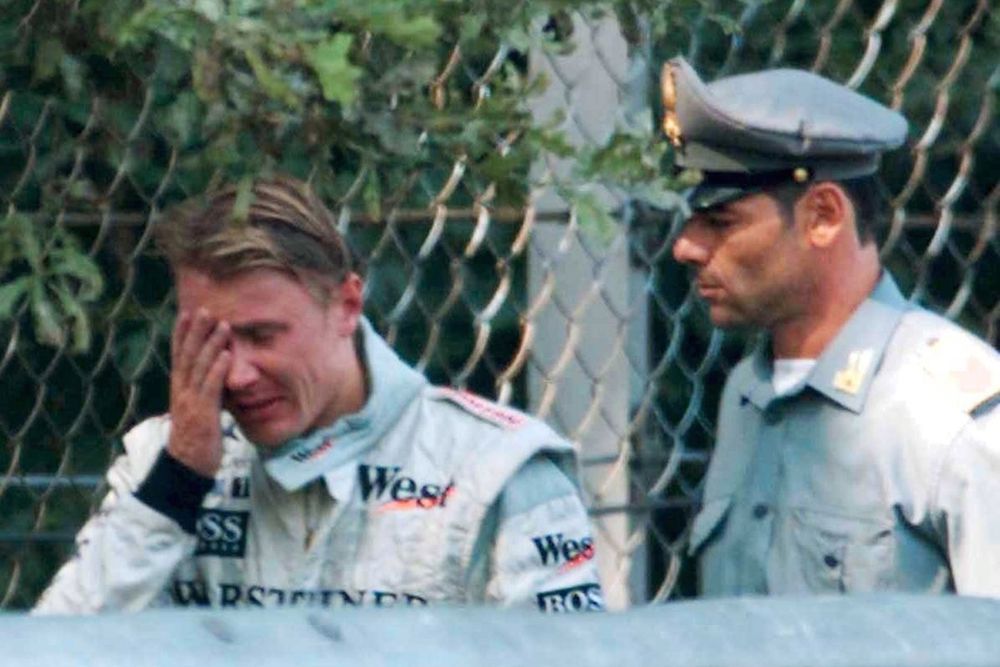

In the race Hakkinen blasted away into a lead which grew and grew, to the point where the gap to Irvine could have been better measured with an egg timer rather than a stopwatch. Then on lap 30 Hakkinen locked his rear wheels mid-way through the first chicane - then a slightly faster configuration than it is now – and spun off into the gravel.

In a momentary lapse of concentration he had downshifted one gear too many, into first rather than second. Mika departed the cockpit as if the car were aflame, threw his gloves down in frustration, sat down behind a tree and wept. But even this was not destined to be a private moment, for it was caught by the prowling TV helicopter…

Read and post comments