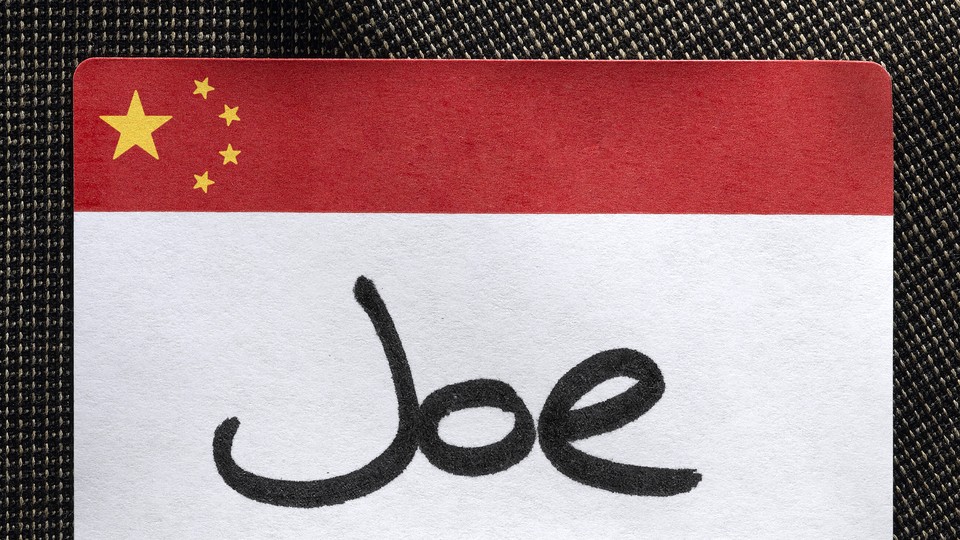

On April 19, 1979, Senator Joe Biden of Delaware was in Beijing, meeting with China’s paramount leader, Deng Xiaoping, when he put Washington’s nascent friendship with the Communists to the test.

That Biden was sitting there at all was remarkable. The United States and China had been implacable foes for decades. In Washington, Deng and his cadres were seen as a dangerous arm of the Red Menace, their conquest of China 30 years earlier bitterly lamented as its “loss” to godless Communism. In Beijing, the Americans were viewed as merciless imperialists, defenders of the Nationalists, the Communists’ mortal enemy ensconced on the island of Taiwan. In 1971, when National Security Adviser Henry Kissinger initially broke the ice with the Chinese Communists, he had to sneak into Beijing secretly. Biden arrived quite publicly as part of a five-member delegation from the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. His six-day tour included visits to a school, factories, and a commune. Still, suspicions remained on both sides: Washington had recognized the Communist regime as the government of China fewer than four months before Biden’s visit.

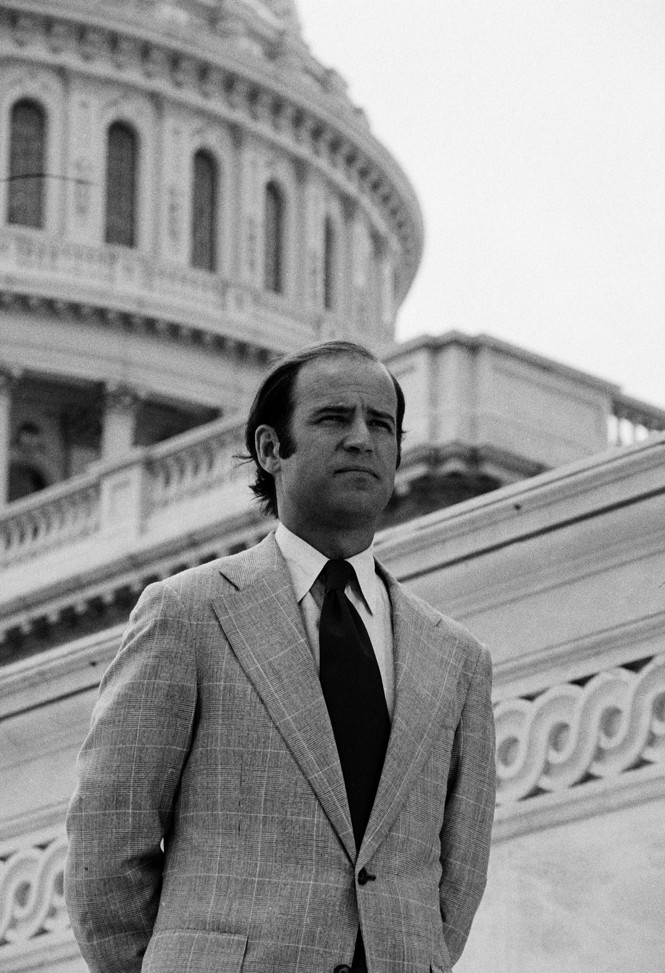

The people in the room could hardly have been less alike as well. Biden, then only 36, was a little-known senator at the beginning of his second term and on his first visit to China. Deng, at 74, was already a historic figure and prominent statesman who had been quite literally fighting for the Communist cause before Biden had been born.

At the time, the meeting held only moderate significance. But today, with Biden in the White House, his conference with Deng looms large. The journey influenced his thinking on China for years to come—and may echo even today. More than that, this glimpse into the past of U.S.-China relations opens a window on their future. Perhaps a closer look at why Beijing and Washington chose to forge a friendship half a century ago can help us understand what’s gone so wrong between them today.

Biden’s query to Deng back then probed the boundaries of the tentative partnership. As a junior senator, Biden had to wait for his turn to speak during the two-and-a-half-hour conference while the more senior members of the delegation took the lead. When he got his chance, Biden opened with a typical folksy quip. “I would like to thank you for giving us time away from your grandchildren,” he told Deng, eliciting laughter from the room. Then he got down to business. “You and other high officials in China have indicated repeatedly what we can or might consider doing to harness the polar bear,” Biden said, referring to the Soviet Union, according to a transcript of the meeting cataloged in a State Department cable. He then asked three questions at one go, the first two about the recently concluded peace process between Egypt and Israel, and China’s interest in purchasing American military equipment. (“If the U.S. is willing to provide us with sophisticated arms and dares to do it, we will dare to accept,” Deng said.) Then he popped the big one. “Would China consider U.S. monitoring stations on Chinese soil?”

Washington and Moscow were at that moment in the final stages of negotiating the second agreement of the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks, or SALT II, which would be signed that coming June. Listening posts were crucial to help the U.S. ensure that the Soviets were upholding their end of the bargain. Washington’s original plan—to use surveillance stations in Iran for the purpose—had been upended by the overthrow of the shah in the Islamic revolution in the months prior. China had its own long border with the Soviet Union (along which the two had shot at each other a decade earlier) and could provide a solution.

Even more intriguing than Biden’s query was Deng’s response. “If you provide monitoring technology, and the sovereignty belongs to China, China will accept,” Deng said. “We can provide you with intelligence and information.” Deng was as good as his word. The groundwork for the stations had been laid during his trip to the U.S. earlier that year, when he secretly visited CIA headquarters. The stations eventually opened in China’s west, conveniently near Soviet missile-testing sites. The U.S. and China were partners in the espionage business.

All of this Cold War maneuvering is ancient history now. But the exchange still resonates. Biden was asking something truly incredible: Would the Chinese Communist Party, which Washington had spent decades and a fortune trying to thwart, join hands with the American republic to spy on its fellow Communists in Moscow? That such an idea was even considered reveals how deeply Beijing loathed the Soviets. But even more, Biden’s question and Deng’s response spotlight the spirit motivating the emerging U.S.-China relationship in 1979. Both countries were pushing past their differences and bitter memories to achieve a bigger purpose. Biden and Deng, sitting in that meeting, knew they had an opportunity to change the world, and they wished to seize it.

The entire episode raises tantalizing questions about the U.S. and China today as their relations deteriorate. If so much was possible in 1979, when the two had much more reason to fear than to trust each other, perhaps the relationship can be rescued in 2022? Perhaps a world scarred by renewed superpower confrontation is not inevitable? And maybe Joe Biden—the man who once asked another paramount Chinese leader for a truly remarkable partnership—is just the man to save it?

[Read: The gamble of Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan]

As a measure of how committed the Chinese Communists were to improved ties with the U.S., Deng was willing to cooperate with Washington and engage with the visiting senators despite their having just twisted the most sensitive thorn in Deng’s side: Taiwan. American leaders may have been taking a big gamble by trusting the Communists; the same was true the other way around.

Taiwan was, and still is, the main point of contention between the two governments. (That was made all too clear earlier this month when House Speaker Nancy Pelosi visited Taiwan, prompting Beijing to respond with extensive military exercises surrounding the island.) The Communist regime then, as now, claimed Taiwan as an integral part of China. Taiwan was then, as now, home to the rival Republic of China, re-established by the Nationalists after they were chased there by the Communists in 1949 at the end of their civil war. The U.S. had maintained recognition of the Republic of China as the legitimate government of China, rather than the Communists’ People’s Republic in Beijing. Recognizing both governments was impossible: The Communists were adamant that there was only one China and relations with the U.S. had to be based on that notion. So when Washington finally instated formal diplomatic relations with Beijing, on the first day of 1979, it had to sever official ties to Taiwan.

America was not, however, willing to throw Taiwan under the bus. The island was still an important link in the U.S. security system in the Pacific. So Congress formulated new legislation, called the Taiwan Relations Act, to solidify its relationship with Taiwan in the absence of formal recognition. Signed into law by President Jimmy Carter only days before Biden’s meeting with Deng, the act ensured Washington’s continued support for Taiwan, even allowing arms sales.

Deng wasn’t happy, and he let Biden and his colleagues know it. “At the time of normalization there was but one China. Please allow me to say frankly, this basis is being undermined,” he said. The U.S. was “interfering” in the foundation of the new relationship, Deng warned. “I would like to advise the people here to pay attention to these ideas,” Deng said, adding, “we will watch the actual actions” of the U.S. toward Taiwan. The Americans got the message. A summary of the meeting in the State Department cable noted that Deng “took a very tough line” on the act.

The senators in the room were the right targets for Deng’s ire. The Senate Foreign Relations Committee had been heavily involved in drafting the Taiwan Relations Act. Nevertheless, Deng moved on from the matter and, later in the conversation, approved Biden’s surveillance stations.

In a sense, that meant the senators had done their job. The conundrum Washington faced then, as now, was striking a balance between backing Taiwan and not offending China, or at least not enough to tank the partnership.

How to achieve that aim had set off a furious debate in Congress before the delegation’s visit. Some members sought to make an unequivocal statement of American support for Taiwan, risking a break with Beijing just as the new relationship was getting started. Biden was not among them. Throughout the proceedings in February and March 1979, Biden endeavored to rein in his more hawkish colleagues. Martin Gold, an adjunct professor at George Washington University, wrote in his book A Legislative History of the Taiwan Relations Act that “of all members on Foreign Relations, Biden was the most openly hesitant about writing into law an unofficial connection with Taiwan. He believed constructing a web of ties and obligations would complicate relations” with Beijing. That’s not to say Biden wanted to abandon Taiwan: He voted in favor of the final bill. But he wasn’t willing to jeopardize the relationship with Beijing, either.

After much wrangling, the senators on the Foreign Relations Committee reached an initial compromise on specific wording regarding Taiwan’s security, and Senator Jacob Javits of New York, another member of the delegation that would soon meet Deng, commented that he’d support the phrasing even if it proved “the breaking point” with Beijing. Biden didn’t agree. “I would like it to be known that I do not accept that premise,” he said. “If I thought this would end it, I would not support this provision.”

Biden expanded on his views during a debate on the Senate floor in early March. “There is a large body of opinion—both in the nation and in this chamber—that is skeptical about the good intentions of the Communist government of China,” he said. “But I maintain that recognition of the Beijing government—the government of nearly 1 billion people, a government that has been in power for nearly 30 years—in no way implies approval of that government’s every policy or of that government’s social or economic system.” Establishing formal relations with the Communist regime was the overdue acceptance of the political facts on the ground in East Asia, he asserted.

Biden criticized Washington’s previous approach to China and Taiwan. “I believe that, after 30 years of deliberate fiction, it is time to set our relationships with China and Taiwan straight.” He referred to the claim that the U.S. “lost” China to Communism. “I, personally, do not believe that China was ever ours to lose,” he said. “In my opinion, the real loss of China for the United States was the loss of contact with the mainland.”

[David Frum: Why Biden is right to end ambiguity on Taiwan]

Today, such remarks are considered heresy. China is now perceived as America’s chief strategic adversary and economic competitor. The policy of engagement with China that Biden advocated in 1979 is maligned as a colossal blunder dreamed up by naive ivory-tower elites. Policy makers like Biden, critics contend, should have known all along that Communist China would never become a democratic society or a trustworthy global partner. Instead, the U.S. willingly participated in the rise of another authoritarian superpower threatening American primacy and democracy.

But that critique takes engagement out of its historical context. Washington’s strategic priority then was the Cold War struggle with the Soviets, and the choices made by Biden and other American politicians in 1979 can be understood and judged only in that light. The China that seems so dangerous today was then a potential game changer in the worldwide contest with Moscow. What appears in hindsight to have been a gross miscalculation made a lot more sense at the time.

Biden’s exchange with Deng flags how he, too, envisioned ties with China within this greater, global context. “What Biden was interested in, what he focused on, what he raised with Deng Xiaoping wasn’t anything to do with China, per se,” Daniel Russel, the vice president for international security and diplomacy at the Asia Society Policy Institute, who advised Biden on China affairs when both served in the Obama administration, told me. “It was all about the Soviet Union and the Cold War … Biden saw China through the lens of the Cold War and the battle against the Soviet Union, which, by the way, was the entire underpinning of normalization” with China.

Biden was not alone in such thinking. The records of his trip reveal that both American and Chinese leaders were motivated to pursue a friendship by shared strategic interests. Deng was no less concerned about Soviet power than his democratic guests were. He warned that “the Soviet Union’s global strategy is to carry out worldwide expansion.” They also spoke about Vietnam, which, as a Soviet ally, was a worry to both sides. Deng had launched a war with Vietnam just that February over Hanoi’s overthrow of the Khmer Rouge regime in Cambodia, which Beijing supported. “Vietnam is the Cuba of the East,” Deng said.

The mutual interests went beyond security. Both sides could see the potential economic gains from growing ties. Biden and his colleagues couldn’t help comparing what they saw in China with Japan, then the rising Asian powerhouse, which the delegation also visited on that journey. “No one travelling from the Beijing area, where bicycles or horses are the predominant mode of transportation, to the Tokyo metropolis, with its traffic jams and bullet trains, could fail to be struck by the profound differences between the economic conditions in the two countries,” the senators noted in their formal report about the trip. There was uncertainty, however, about China’s economic direction. Deng had launched his free-market reforms only months before Biden’s visit, and though the senators judged (correctly, as it turned out) that “the leaders are determined to persist in this course for several years to see if it can speed up China’s progress,” the future of the program, they recognized in the report, was a matter of guesswork. Now, four decades later, we know how successful Deng’s program would become. In 1979, when China was among the world’s poorest countries, that future wasn’t much more than a dream.

The delegation had no illusions, however, about Deng’s ultimate goal: strengthening the Chinese economy. Today, Chinese propagandists accuse Washington of trying to “keep China down” by containing its economic development. But if the U.S. wished that China would remain poor and isolated, Washington would never have cooperated with Deng’s reforms in the first place. At the time, the senators saw promise in the Chinese economic program, not menace.

[Read: How China is doing Biden’s work for him]

The ideas Biden held about China on that trip to Beijing stuck for much of his career. In 2011, then–Vice President Joe Biden, referring to that initial journey to China, wrote in The New York Times, “I remain convinced that a successful China can make our country more prosperous, not less. As trade and investment bind us together, we have a stake in each other’s success.”

Another decade on, President Joe Biden sounds very different. Gone is the wide-eyed optimism about a hopeful future for the U.S. and China. In its place is Biden the Cold Warrior. The U.S. “must meet this new moment of advancing authoritarianism, including the growing ambitions of China to rival the United States,” he said in a 2021 speech. On Taiwan, too, his tone has changed. He no longer appears as worried about alienating Beijing by backing Taiwan. When asked at a Tokyo press conference in May whether the U.S. would defend the island militarily from a Chinese attack, Biden simply said: “Yes. That’s the commitment we made.”

Yet Biden’s long-held belief in engagement seems to linger. Though he has retained many aspects of Donald Trump’s policies, including tariffs and sanctions, their approaches are fundamentally distinct. Trump consistently derided engagement as an almost traitorous folly perpetrated by “globalists” against American interests. Biden maintains some hope for continued collaboration with Beijing. “We’ll confront China’s economic abuses, counter its aggressive, coercive action to push back on China’s attack on human rights, intellectual property, and global governance,” Biden once explained. “But we are ready to work with Beijing when it’s in America’s interest to do so.”

To some critics, that view makes Biden a sheep in wolf’s clothing. Once a China appeaser, always a China appeaser, they believe. But drawing a direct line in his thinking from 1979 to 2022 is overly simplistic. Biden “is not ideological and his views on China are not fixed,” Ryan Hass, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, wrote to me. “He is comfortable holding seemingly inconsistent viewpoints on China, at once emphasizing the importance of democracy prevailing over autocracy and … urging the United States and China to find ways to coexist amidst competition.”

Perhaps that makes Biden the right man at the right moment. As the U.S. and China descend into superpower confrontation, Biden still holds out hope that the worst can be avoided—or better still, that the two can find ways to align on crucial global issues, such as climate change. And with his longtime ties to and experience with Chinese leaders, he may have a fighting chance. At the very least, Biden keeps the two sides talking. In July, Biden and China’s new paramount leader, Xi Jinping, had a two-hour conversation and, in November, a three-and-a-half-hour conference (though these two meetings were not conducted face to face).

“The good news,” the Asia Society’s Russel told me, “is that in this cacophony of chest-pounding U.S. politicians in Washington who are all calling for China’s blood, there’s certainly one, who happens to be the president of the United States, who … understands that there is both the necessity and the possibility of China constructively contributing to some common goals and some global goods. The riddle is how to unlock that cooperation.”

Much has changed since Biden met Deng in 1979. The gargantuan power imbalance that existed between the U.S. and China then has narrowed significantly, and Beijing’s ambitions have correspondingly widened. During the Cold War, they shared a common enemy in the Soviet Union; today, Xi has forged a partnership with Russia against America. Rather than seeking to join the U.S.-led global order, as Deng did, Xi is working to subvert it. Though Deng and Biden saw mutual economic benefits from tighter ties, Xi and Biden envision fierce competition in global technology, trade, manufacturing, and infrastructure. “Biden thinks he can have it both ways, and achieve what his predecessors failed to accomplish: Get tangible policy wins with China while constraining its geopolitical advance,” Michael Sobolik, a fellow at the American Foreign Policy Council, wrote to me. However, the Chinese Communist Party “doesn’t want to live in the liberal internationalist world that Biden is trying to build. That’s why Biden’s China policy won’t ultimately work.”

Examining the exchange between Biden and Deng from 1979 gives a sense of what may be missing in U.S.-China relations today: a mutual interest in achieving shared goals. The two had their disagreements back then too—many of them the same as today, such as the fate of Taiwan. But Washington and Beijing were able to set those aside, the best they could, in pursuit of bigger gain. The two needed each other.

Today, they still do—to tackle pressing global problems or attain continued economic benefits. But these shared interests are becoming consumed by their strategic and ideological differences. At the moment, neither Beijing nor Washington seems willing or able to look past them. Until then, the spirit of ’79 may be history.