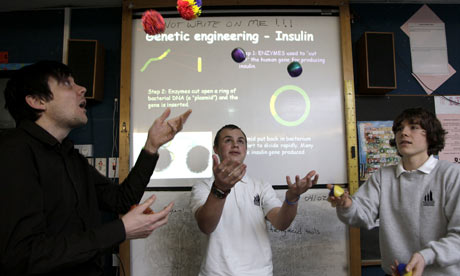

I've been back to school: year 10 biology at Monkseaton High, near Newcastle, to be precise. Over the last four years, the state secondary school has pioneered an innovative method of teaching it calls "spaced learning" – intensive 20-minute PowerPoint presentations, which are repeated twice after 10-minute breaks for physical activity. Pupils play basketball, or juggle, or spin plates, to rest their minds between the learning.

Results, according to the head teacher, Paul Kelley, have been astonishing.

In one trial, 48 year 9 pupils took a GCSE biology exam (a year before they should) after a 90-minute spaced learning class. The average score was 58%. A year later, as year 10s, the same students sat a different science module after four months of conventional teaching. The average score was 68% but more than one in four actually scored better in the first paper.

The theory behind spaced learning is actually derived from neuroscience and the work of a US scientist called Douglas Fields. Kelley was inspired to try to put Fields' findings into practice when he read in the Scientific American of his research into what stimulated long-term memories in the brains of rats.

Kelley is an unusual and charismatic headteacher and his aspirations for spaced learning are radical. He believes it could be used widely – not just in science but in history, and even art – to swiftly acquire basic knowledge and free up huge swaths of the school day for more creative endeavours.

Some academics are enthusiastic. Some are sceptical. "The idea that this is a panacea is a harmful exaggeration," says Alan Smithers, professor of education at the University of Buckingham. Short intense learning and physical breaks makes good sense, but what if spaced learning reduces teaching to mindless rote-learning for the passing of exams? Do these intense sessions suit every pupil? Will every teacher be good at teaching in such a way? If spaced learning means you can swot up for a GCSE in three days, what does that say about the credibility of the exam system?

After my one hour lesson, I felt the method was effective: when I sat a GCSE paper five days later I remembered images and concepts from the lesson quite vividly. But I'm still not sure I believe that my recall was related to neurological discoveries from observations about the brains of rats. Scientists would say this betrays my limited grasp of science, and they would be right. As well as what is being triggered inside my hippocampus, I would relate my apparently successful learning to the impact of a good teacher, the novelty factor of "different" lessons, the positive atmosphere in the school and the character of the class I was with.

Neuroscience may have some answers. I'd be interested to know what teachers, scientists and pupils think.