Who are the most powerful radicals in Britain today? If you believe their own rhetoric, it is the Conservative party. They have trumpeted all sorts of policies, including changes to housing rules and business rates, as “radical”. And they celebrate radicals in their history: on the recent death of Geoffrey Howe, George Osborne recalled him fondly as a “quietly spoken radical”, no doubt much better than a shouty radical.

Being radical, in these times, is excellent. Unless you are the wrong sort of radical – an adherent, say, of “radical Islam”. In that case you will need to be subjected to “deradicalisation”. Is there any way we can apply a programme of deradicalisation to the government? It might look, after all, as though the idea of a radical Conservative is a contradiction in terms. You can’t change everything while keeping it the same. What does “radical” even mean these days?

Radical literally means “pertaining to roots”, from the Latin radix. (Where we also get the name for that puce superfood, the radish.) The political use of “radical”, therefore, signals a desire to reach down to the very roots of something in order to change it, or reform it utterly. But who will admit that his proposed policy only fiddles around the upper foliage of a problem? No one. So a “radical” policy is just any change you want to advertise in advance as being effective. It essentially means nothing other than “very good” or “enormous”. Radical, man.

In modern western politics we normally associate the idea of a “radical” with the left. And so it began in the late 18th century, when campaigners lobbying parliament to extend the right to vote grouped under the banner of “radical reform”. From then on, radicals were generally leftists or progressives. But there came a split, and a reappropriation. As Raymond Williams points out in his indispensable Keywords, by the end of the 19th century there was already “a clear distinction between Radicals and Socialists, and in the course of time most Radical parties, in other countries, were found considerably to the right of the political spectrum”. In which case the current Conservative war on public institutions might well be described as “radical”.

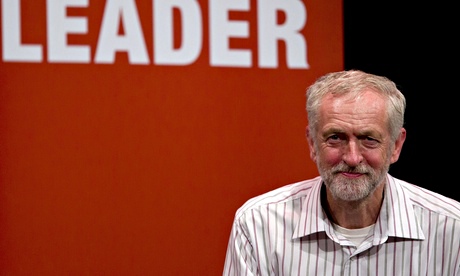

The word’s historical journey also helps us to make some sense of the curious fact that, while the Tory press routinely urges Cameron and Osborne to be even more “radical” in their policies on “welfare reform” and the like, the left-leaning media express their worries about Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership of the Labour party by employing the suspicious epithet “radical”, while his own supporters are careful to disavow any radicalism at all.

What about the radicals it’s mandatory to fear? To call Islamic State and similar groups “radical Islam” attempts to capture their vicious authoritarianism, but etymology might recommend against it, as well as the ubiquitous term “radicalisation” to describe British Muslims who become sympathetic to Isis. “The level of radicalisation taking place across the UK is reaching unprecedented levels,” warned Keith Vaz pleonastically in August. But if you describe people who enjoy cutting the heads off other people as belonging to “radical Islam”, you might thereby rhetorically endorse their own arguable claim that they represent the true roots of the religion.

The antidote to such radicals, of course, are “moderate Muslims”, as the condescending phrase has it. Well, “moderate”, as Williams notes wryly, “is often a euphemistic term for everyone, however insistent and committed, who is not a radical.” The approving use of “moderate” implies that all decent Muslims should hold their beliefs only half-heartedly, while the Conservative party revels in its radical extremism for the good of us all. (The moderate conservatives, of course, are all crammed into the Blairite rump of the Labour party.)

Can we draw any helpful lessons from this confusing tangle of uses? It would be good to know when “radical” means something nice and when it means something nasty. Should I take a radical attitude to obeying laws I find preposterous? Should you advertise yourself as a baker of radical cronuts? In the end, the political valency of “radical” simply depends on the power relations between groups. Labour is circumspect about calling itself radical because it doesn’t want to frighten the horses. But the Tories can call themselves radical because they are in office for the next five years and can do whatever they like, which apparently includes cutting working tax credits after promising not to during the election campaign. Now that’s a radical approach to governing with the public’s consent.