The vast entrance hall at London’s Tate Modern gallery has seen art on an epic scale since it opened in 2000, from Chinese artist Ai Weiwei’s Sunflower Seeds, which filled the space with millions of hand-made porcelain seeds, to Icelander Olafur Eliasson’s The Weather Project, which installed a giant, glowing yellow sun and atmospheric mist.

Yet before all this, the hall was a working space that held huge generators for the Bankside oil-powered station, which generated electricity from 1952 to 1981 and ultimately became the Tate Modern. In fact, in a nod to its history, the hall is named the turbine hall.

This successful conversion from industrial to social space is something that many power companies are going to have to look at in the future, as their traditional power stations become redundant – with much of their capacity replaced by renewables.

“In less than five years, renewables have begun to account for 40% of the Italian demand for energy,” explains Enrico Viale, head of global generation at energy multinational Enel. “Most of our oil or gas fired power plants are now shut down for large parts of the year.”

In fact, Europe has been experiencing a drop in demand for electricity since the end of the last decade. This drop is partly due to the world recession but the growth in renewable energy has also had a major impact on the traditional model, where energy was produced in a handful of large plants and then transmitted to users.

Energy efficiency and the management of power through smart meters and smart grids has also played a role in the drop in demand, as consumers take more control over the energy they use.

In Italy, these changes have led to a discussion about the future of the country’s ageing and increasingly uncompetitive power plants, whose production capacity is now largely superfluous to national needs.

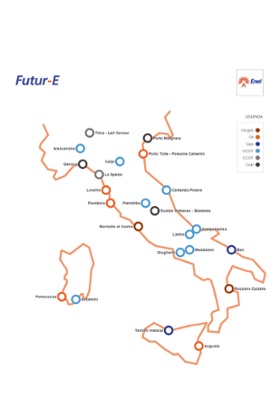

Enel has 23 such plants, with a total capacity of 13 gigawatts. Some have only been called upon to act as reserve capacity for several years now, while others have seen or are going to see their permits to operate expire. A handful have simply come to the end of their technological life. All of them are no longer competitive in the local energy market.

“All of this led us to say: ‘Let’s review our fleet’ and that’s why we launched a national project called Futur-E,” explains Viale.

Yet these power plants are also an important part of Italy’s industrial heritage, he continues, which still have huge potential for new and different uses. Through Futur-E, Enel has begun to assess these sites, looking for ways to reinvigorate them, although, as Viale adds: “Each site is different, with its own unique characteristics, so no single strategy will fit all scenarios.

“We are looking to find solutions that can give new life to these sites, perhaps as museums, shopping malls or logistic hubs. We want to seek those ideas with the full cooperation of the local communities and mainly let somebody else develop this new opportunity – creating shared value has always been an important part of the way in which Enel operates.”

Enel is also aware that around 600 people rely on the power plants for their livelihoods and is offering everyone affected by the closures new roles in other areas of the Enel’s business.

Enel is set to involve many different stakeholders in sites’ transition, from employees to local communities and businesses. The company is also working with specialist firms to analyse each site and identify possible options for the plants.

Some, explains Viale, could continue to generate electricity by being converted to another technology. Renewable energy is of course one option; and Enel is looking to install biomass units in some plants.

A second group is made up of plants that are no longer suitable sites for power generation, usually because housing and residential areas have grown up around them since they were first built. These could be suited to completely new uses, he says, just like the Tate Modern, which is now one of the most visited modern art galleries in the world.

A third group is plants that have little chance of being used for the generation of electricity again, but have a significant industrial footprint. For these sites, Enel is looking to facilitate a whole range of alternative proposals to be pursued by a third party, actively involving communities and local institutions to find ways in which the sites can continue to make a valid contribution to the area.

It’s a process that is leading to many new and exciting models, says Viale. For example, Enel is looking at the possibility, proposed by an external organisation, of converting the old Piombino oil-fired plant in Tuscany into a shopping mall that will preserve some of the plant’s old industrial features, while also including new landscaping.

“This is just one suggested solution,” says Viale. “Others include innovative technological factories, data centres and logistic hubs. We are receiving lots of letters of interest from different parties and we’re now working to find the best solution for each plant.”

“In any case we want to act selecting or fostering a destination for the plant but then leaving the opportunity to a new company, partner, community” adds Viale. “We are not escaping from our footprints, but looking at the future with an open minded approach”

For other power plants, the company is promoting an international contest, inviting architects, NGOs and other similarly qualified organisations to put forward their own designs for the sites.

The first site in the contest is at Alessandria in Piemonte, north west Italy. The turbo gas power plant opened in 1978, and was decommissioned in 2013 due to a drop in production.

Alessandro Balducci, vice rector of the Polytechnic University of Milan, will be one of the judges. He says an important priority for the contest is that the ideas should reflect local needs and also provide opportunities for local people.

“There are different types of benefits that can arise for the local communities,” he explains. “The intervention can provide job opportunities, but also an increased usability of the site from the public, the promotion of tourism and cultural activities as well as the valorisation of the context and the nearby areas.”

Marcello Ferralasco, assessor for territorial and strategic development for the Alessandria municipality, says: “Today the site doesn’t have any economic function but continues to occupy a portion of our territory. We expect the ideas collected by the international contest to give new vitality to the local environment and allow new employment opportunities too.”

Viale suggests the work in Italy is going to be an important testing ground for ideas that could be applied across the globe. “We are not alone in Italy in having such an overcapacity,” he says, “For such a huge change in the Italian energy system a national or systemic approach would be useful. We have set up an integrated project within our organisation and we expect interesting results… [by] the end of this year.”

For details about the contest for ideas for the Alessandria power plant, see the Futur-E site.

Content on this page is paid for and produced to a brief agreed with Enel, sponsor of the energy access hub on the Guardian Global Development Professionals Network.