India’s 705 Scheduled Tribe (ST) communities – making up 8.6% of the country’s population – live in 26 States and six Union Territories.

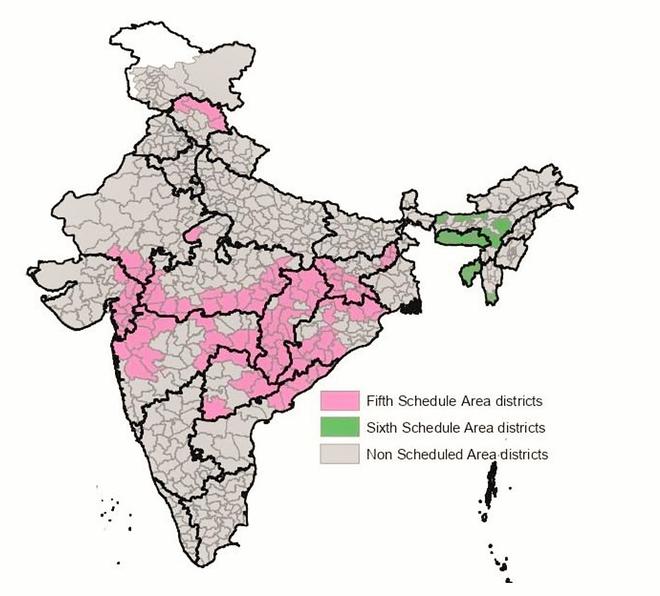

Article 244, pertaining to the administration of Scheduled and Tribal Areas, is the single most important constitutional provision for STs. Articles 244(1) provides for the application of Fifth Schedule provisions to Scheduled Areas notified in any State other than Assam, Meghalaya, Tripura, and Mizoram. The Sixth Schedule applies to these states as per Article 244(2).

A place for ST communities

Scheduled Areas cover 11.3% of India’s land area, and have been notified in 10 States: Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Odisha, Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, Gujarat, Maharashtra, and Himachal Pradesh. In 2015, Kerala proposed to notify 2,133 habitations, five gram panchayats, and two wards in five districts. It awaits the Indian government’s approval.

However, despite persistent demands by Adivasi organisations, villages have been left out in the 10 States with Scheduled Areas and in other States with ST population. As a result, 59% of India’s STs remain outside the purview of Article 244. They are denied rights under the laws applicable to Scheduled Areas, including the Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act 2013 and the Biological Diversity Act 2002.

In 1995, the Bhuria Committee, constituted to recommend provisions for the extension of panchayat raj to Scheduled Areas, recommended including these villages, but this is yet to be done. The absence of viable ST-majority administrative units has been the standard bureaucratic response – an argument that has also been used to demand the denotification of parts of Scheduled Areas where STs are now a minority due to the influx of non-tribal individuals.

Scheduled Area governance

The President of India notifies India’s Scheduled Areas. States with Scheduled Areas need to constitute a Tribal Advisory Council with up to 20 ST members. They will advise the Governor on matters referred to them regarding ST welfare. The Governor will then submit a report every year to the President regarding the administration of Scheduled Areas.

The national government can give directions to the State regarding the administration of Scheduled Areas. The Governor can repeal or amend any law enacted by Parliament and the State Legislative Assembly in its application to the Scheduled Area of that State. The Governor can also make regulations for a Scheduled Area, especially to prohibit or restrict the transfer of tribal land by or among members of the STs, and regulate the allotment of land to STs and money-lending to STs.

These powerful provisions, authority, and special responsibility vested with Governors, with the President’s oversight, have largely remained a dead letter, except briefly in Maharashtra in 2014-2020.

It was only when Parliament enacted the Provisions of the Panchayats (Extension to Scheduled Areas) Act, or PESA, in 1996 that the intent of the Constitution and the Constituent Assembly actually came alive. State Panchayat laws had empowered the elected panchayat bodies, rendering the gram sabhas moot. But PESA empowered the gram sabhas to exercise substantial authority through direct democracy, and stated that structures “at the higher level do not assume the powers and authority” of the gram sabha.

Who decides a Scheduled Area?

The Fifth Schedule confers powers exclusively on the President to declare any area to be a Scheduled Area.

In 2006, the Supreme Court (civil appeal nos. 484-491) held that “the identification of Scheduled Areas is an executive function” and that it doesn’t “possess the expertise … to scrutinise the empirical basis of the same”.

In 2010, the Jharkhand High Court (W.P. no. 689) dismissed a challenge to the notification of a Scheduled Area because the ST population there was less than 50% in some blocks. The court observed that the declaration of a Scheduled Area is “within the exclusive discretion of the President”.

The identity of a Scheduled Area

Neither the Constitution nor any law provides any criteria to identify Scheduled Areas. But based on the 1961 Dhebar Commission Report, the guiding norms for their declaration are: (a) preponderance of tribal population, (b) compactness and reasonable size of the area, (c) a viable administrative entity such as a district, block or taluk, and (d) economic backwardness of the area relative to neighbouring areas.

No law prescribes the minimum percentage of STs in such an area nor a cut-off date for its identification. This said, the 2002 Scheduled Areas and Scheduled Tribes Commission had recommended that “all revenue villages with 40% and more tribal population according to the 1951 census may be considered as Scheduled Area (sic) on merit”. The Ministry of Tribal Affairs communicated this to the States in 2018 for their consideration, but elicited no response.

Compactness of an area means that all the proposed villages need to be contiguous with each other or with an existing Scheduled Area. If not, they will be left out. But contiguity is not a mandatory demarcating criterion. One example is Kerala’s pending proposal, which ignores the conditions.

The Bhuria Committee recognised a face-to-face community, a hamlet or a group of hamlets managing its own affairs to be the basic unit of self-governance in Scheduled Areas. But it also noted that the most resource-rich tribal-inhabited areas have been divided up by administrative boundaries, pushing them to the margins.

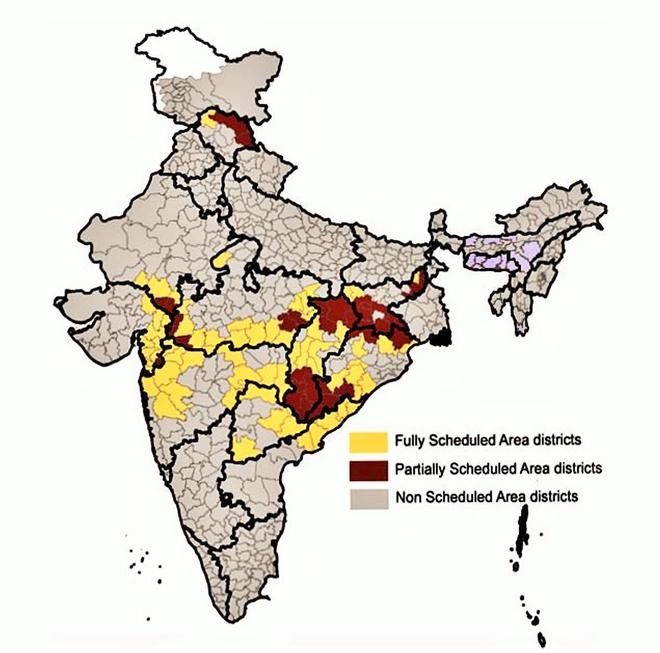

As such, determining the unit of the area to be considered – whether a revenue village, panchayat, taluka or district, with an ST-majority population – gave way to arbitrary politico-administrative decisions.

Settling the debate

PESA’s enactment finally settled this ambiguity in law. The Act defined a ‘village’ as ordinarily consisting of “a habitation or a group of habitations, or a hamlet or a group of hamlets comprising a community and managing its affairs in accordance with traditions and customs”. All those “whose names are included in the electoral rolls” in such a village constituted the gram sabha.

The Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act – a.k.a. FRA – 2006 adopted this definition. Here, too, the gram sabhas are the statutory authority to govern the forests under their jurisdiction. As a result, the PESA definition of a village expanded it beyond Scheduled Areas to forest fringes and forest villages as well.

However, gram sabhas are yet to demarcate their traditional or customary boundaries on revenue lands in the absence of a suitable law. FRA 2006 requires them to demarcate ‘community forest resource’, which is the “customary common forest land within the traditional or customary boundaries of the village or seasonal use of landscape in the case of pastoral communities, including reserved forests, protected forests and protected areas such as Sanctuaries and National Parks to which the community had traditional access”.

The traditional or customary boundary within revenue and forest lands (where applicable) would constitute the territorial jurisdiction of the village in the Scheduled Area.

To-do list

In sum, all habitations or groups of habitations outside Scheduled Areas in all States and Union Territories where STs are the largest social group will need to be notified as Scheduled Areas irrespective of their contiguity. Second: the geographical limit of these villages will need to extend to the ‘community forest resource’ area on forest land under FRA 2006 where applicable, and to the customary boundary within revenue lands made possible through suitable amendments to the relevant State laws.

Finally, the geographical limits of the revenue village, panchayat, taluka, and district will need to be redrawn so that these are fully Scheduled Areas.

C.R. Bijoy examines natural resource conflicts and governance issues.