Since Friday, when the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, I’ve been grappling with a sense of gnawing disbelief at how instantaneously the contours of reality can change. The fact that the seismic change in protections for women in America could easily be seen coming didn’t make its arrival any less destabilizing. On Thursday, we had a constitutional right to abortion. On Friday, we didn’t. In a blink, foundational ideas about equality and justice dissolved and recalibrated themselves as something much more brutal and atavistic. The shift was so immediate that my brain still can’t come to terms with the facts: that so many women will die, will be financially ruined, will never get to know who they could have been if they hadn’t been forced by the state to become mothers. That doctors may become so fearful of intervening in medical emergencies such as miscarriages and ectopic pregnancies that patients could face septic shock or hemorrhage. That, robbed of the opportunity to have legal abortions, pregnant people are already trading information about illegal, unregulated, and likely more dangerous options.

History doesn’t exactly repeat itself, and America post-Roe won’t be quite as it was before it, as Jia Tolentino pointed out in The New Yorker: The proliferation of technological surveillance and data harvesting puts people seeking to end unwanted pregnancies, in certain ways, in more precarious positions than they were in 50 years ago. But watching The Janes, a recent HBO documentary about a women’s movement that organized an estimated 11,000 “safe, affordable, illegal abortions” in Chicago from 1969 to 1973, I noticed sonorous echoes between pre-Roe America and our present day. The patchy state of reproductive rights in the U.S. after New York legalized abortion in 1970 led to profound disparities in care. In states where abortion remained illegal, middle-class (usually white) women with the means to travel could have their pregnancies terminated safely and legally elsewhere. Low-income women, predominantly women of color, couldn’t. The illegality of abortion in Chicago didn’t stop women from trying to terminate their pregnancies. It just meant that they were forced to seek out unsafe ways of doing so: self-administered internal injuries using sharp objects or carbolic acid; Mob-sponsored back-alley operations; “doctors” who demanded sexual favors from women or left them alone in motel rooms to bleed to death. “What was seared into my brain,” a then–medical student at Cook County Hospital says in the documentary, “was what desperate people will do when they think they have no other choice.”

[Read: The calamity of unwanted motherhood]

Into this moment, four years before Roe v. Wade was decided in 1973, came the Jane Collective, a grassroots organization of young women who provided access to terminations for women who had no other options. They saw what they were doing as an ethical imperative. There was “a philosophical obligation on our part to disrespect a law that disrespected women,” Jody Howard, one of the group’s leaders, says in an archival interview. (Howard died in 2010.) Some of them had had illegal abortions themselves. Many were also tired of being excluded or silenced by other activist organizations at the time, whose leaders seemed unconcerned about women’s rights and were hostile to members who tried to speak up about women dying on the reproductive front lines.

In its earliest days, Jane built on the work of its co-founder Heather Booth, who was a student at the University of Chicago when a friend asked her for help getting an abortion for his sister, who was pregnant and near-suicidal. Booth contacted a doctor she knew from the civil-rights movement, who agreed to perform the procedure, and subsequent others as word spread. As demand became too much for Booth to manage, she recruited other women; they named the group Jane for clandestine purposes, and because it was a “nice simple name,” one member explains. They left flyers around town reading Pregnant? Don’t want to be? Call Jane. Volunteers would drive patients to their initial consultations, and then to an apartment or a house where the procedures were performed. Patients paid whatever they could afford.

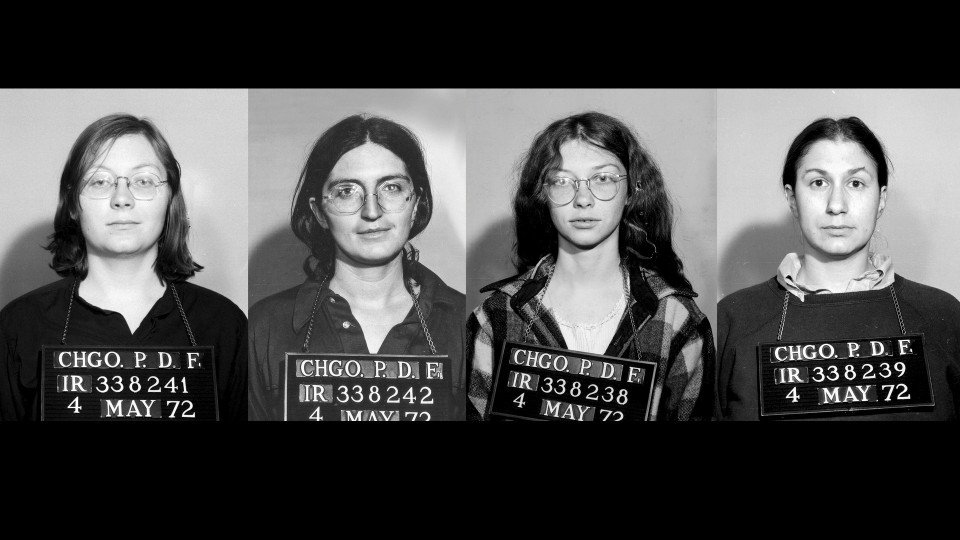

Jane was far from perfect. As time went on, its organizers became more and more demographically different from the women they treated. Few questions were asked about the medical credentials of the man who performed most of the abortions early on, a former construction worker who’d seemingly trained with a Mafia doctor and appeared largely in it for the money. (He was also “highly skillful and treated the women well,” one Jane member says, while another woman interviewed described her abortion, perhaps strangely, as “the best medical experience I ever had.”) Organizers were at times naive about the fact that they were operating in plain sight of the Chicago Police Department, who tended to turn a blind eye, likely because of the women’s middle-class credentials and the fact that they occasionally helped the cops’ daughters and mistresses.

[Read: When a right becomes a privilege]

But the lesson from The Janes is that, in the absence of justice and political power—and without any meaningful acknowledgment of the right that human life has inherent value worth preserving even after it leaves the womb—there’s enormous potential for collective action. This post-Roe moment, Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez wrote on Instagram last week, is “really about a choice all of us will have to make in life, either consciously or unconsciously: will I be a person who is safe and creates good for others? Will I be a person who stands up? … Much of our work is about scaling existing solutions, many created by small committed groups of people, that others haven’t seen or don’t even know are around the corner.” On Reddit, an “Auntie” network has been providing assistance, shelter, and resources to pregnant people in need of abortions. Activists are helping inform women about how to access abortion pills and how to avoid leaving digital footprints that might be used to later indict them.

The operations of the Jane Collective were about more than serving people in need. They were about envisioning and protecting a more hopeful future for women altogether, one that didn’t include being forced to bear unwanted children. “Coming through the service transformed other women. And that was our intent,” one Jane organizer says in the documentary. “We were building a new world.” That the foundations of that vision have been so systematically and methodically demolished shifts the burden to a new generation to try to save the lives and choices of women once more. After Roe v. Wade passed, The Janes reveals, Cook County Hospital closed its septic-abortions ward, for patients who’d been grievously injured by unsafe procedures. The clinic was no longer needed: a demonstrable victory for a legal precedent that no longer stands.