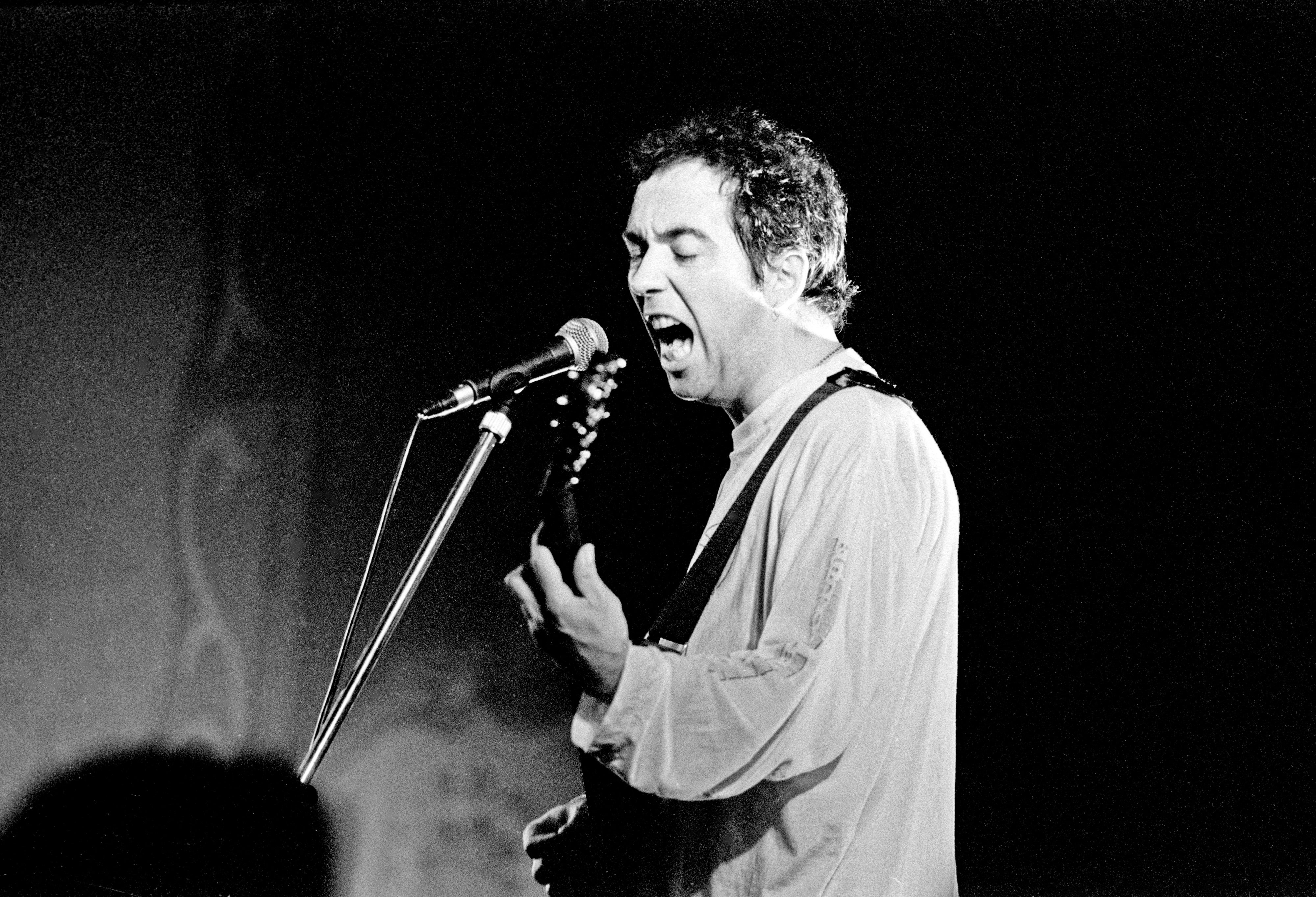

As the 1980s began, Pete Shelley found himself at a low ebb. Since their very first gigs in 1976, his band Buzzcocks had easily distinguished themselves among the punk-rock moshpit. Disdaining the scene’s rote “bad boy” pantomiming, Shelley’s soft Bolton tones sounded a rare note of reason amid a frothing 1977 BBC Television debate on whether punk was “a threat to British society”, while the following year he told Melody Maker that Buzzcocks were “just four nice lads, the kind of people you could take home to your parents”. And he’d fused punk’s velocity to timeless songwriting across hits like “What Do I Get?”, “Love You More” and, of course, “Ever Fallen in Love (With Someone You Shouldn’t’ve)”, displaying a feel for melody and a lyrical sophistication far beyond his peers.

Three albums in, however, Buzzcocks were now running on empty. A burned-out Shelley had called time on touring and entered “an introspective phase”, leaning heavily on psychedelics for guidance and inspiration. While making 1980 single “Are Everything”, Shelley told Trouser Press he took acid “for every part of it – recording, mixing. It was my acid song”. Still, he struggled to “get the ideas I had across” to his Buzzcocks bandmates. “I wasn’t doing myself any good, I was just wringing out my soul to get songs done.”

Things got so bad Shelley even dipped a toe in Scientology (though he later admitted he “couldn’t make head nor tail” of L Ron Hubbard’s textbook Dianetics). But in early 1981, as he began demoing a mooted fourth Buzzcocks’ LP at Genetic, the studio of producer Martin Rushent, an unexpected breakthrough arrived. Having left the rest of Buzzcocks at home, Shelley approached Rushent’s Roland MC-8 Microcomposer – a primitive sequencer that cost the producer the 1977 equivalent of £25,000 – and worked on a song he’d begun in 1974. Eight hours later, Rushent heard the results and declared: “This is not a demo any more – this is a record!”

That record was “Homosapien”, and not only would it signal the end of Buzzcocks, it marked Shelley’s pioneering turn towards synth-pop – one that would see this most radio-friendly punk banned from the airwaves by a curmudgeonly BBC.

Little in Buzzcocks’ discography suggested this new direction. The group had formed in February 1976 at Bolton Institute of Technology (BIT), after electronics student Pete McNeish saw fellow student Howard Trafford’s advertisement for musicians to perform the Velvet Underground’s experimental-rock epic “Sister Ray”. Seduced by punk rock via an NME review of Sex Pistols’ first gig at the 100 Club in London later that month, the pair travelled to the capital to seek out Malcolm McLaren, saw the Pistols twice and changed their names to Pete Shelley (after the Romantic poet) and Howard Devoto. They booked the Pistols to play their legendary first Manchester gig in June 1976; by January 1977, their own self-released debut EP, Spiral Scratch, sold out its initial thousand-copy run in four days. Devoto exited several months later (to form Magazine), and Buzzcocks – now led by Shelley – went on to release a volley of brilliant singles that married punk dynamics to classic pop structures, and lyrics that rewrote old romantic clichés as new, and stingingly personal.

Yet before Shelley connected with Devoto, his musical interests had been altogether more esoteric. In early 1974, Shelley had built an oscillator – a primitive synthesiser – and started an electronic music society at BIT, where he played records by avant-garde German groups such as Can and Neu!, and “tormented people” by playing his own experimental tracks. He pushed further with his homemade oscillator, “putting myself in the circuit” by touching its wiring with his flesh and “becoming another resistance”. This gave Shelley a “touch-sensitive way of coming up with really weird things, adding echo and other effects, too”.

Shelley would belatedly release an album of these electronic experiments, Sky Yen, in 1980, his interest in electronic and experimental music continuing on into Buzzcocks. “Pete would always play records by Neu!, Can, Kraftwerk and Cabaret Voltaire,” remembers friend Joey Headen, who first met Shelley in 1977. “We passed each other in the toilets of [Manchester punk venue] Electric Circus and he said, in his Bolton accent, ‘Ooh, you look just like Joey Ramone.’ And yeah, I did – leather jacket, dark glasses, long brown hair. That’s where my name came from.”

Already a Buzzcocks devotee – “the harmonies, the buzzsaw guitars, Pete’s singing – there was nothing not to like” – Headen became a regular at Shelley’s home. “There was always a gang of us in and out of his house all the time, listening to music, reading books. We were there when Pete came up with ‘Everybody’s Happy Nowadays’. He’d written it upstairs, then he came down, sat on the edge of the couch and played it to all of us. Pete and Steve [Diggle, Buzzcocks’ lead guitarist] were churning out songs on a weekly basis. They’d kick off a gig with a new instrumental, and a few weeks later it’d be out as a single.”

Headen became a close friend of Shelley’s and part of Buzzcocks’ inner circle. But even he didn’t believe the news in 1981 that they were splitting up. “It was something you couldn’t even contemplate. ‘They’re not gonna split up – they’re the Buzzcocks! They’ve always been the Buzzcocks.’ But once Pete got started on that Homosapien stuff with Martin, it was clear he was going to continue with that, no matter what.”

Even though he’d produced all three Buzzcocks’ albums – plus three by The Stranglers – Martin Rushent was no punk purist. “Martin was a huge Motown fan, and he loved commercial pop music,” remembers Jim Russell, who first met Rushent in the early Seventies when he drummed on an album by prog rock band Curved Air, which Rushent produced. Later, Rushent set up his Genetic studio in a barn at his Berkshire home, with an eye to specialising in electronic music. He spent heavily on then-primitive and incredibly expensive and rare synthesiser and recording gear for Genetic.

“He had Fairlight synthesisers and Synclaviers,” says Headen. “The Synclavier was the price of a three-bedroom house at the time. There were only two in the country – Peter Gabriel and Kate Bush shared the other one. Martin would get calls from Paul McCartney and Mike Oldfield, asking to borrow it. But we could play around and doodle on them every night.”

This was where Shelley recorded the Homosapien album, playing his beloved 12-string guitar, but also working with futuristic equipment like the Linn Drum and the Jupiter 6 synthesiser. By day, Elvis Costello was recording what became his Punch the Clock album. By night, Shelley ran electronic riot. It was early days for synthesiser pop and, Gary Numan aside, there was little precedent for the change in direction Shelley was about to take. But while Headen remembers the new music was “a shock, it wasn’t that much of a shock. Because that was Pete’s voice there, even if there were no revving guitars”.

The title track was the lead single, its edgy, compelling mix of Cro-Magnon drum machines, 12-string guitar and throbbing synth the bed for the boldest lyrics of Shelley’s career. “I’m the shy boy, you’re the coy boy,” he sang. “I’m the cruiser, you’re the loser… Homosuperior, in my interior.” Shelley’s Buzzcocks songs had swapped punk-rock’s standard politics, cynicism and nihilism for the battleground of the heart, telling Melody Maker in 1978: “People say ‘Punk songs aren’t meant to be about love’. But why should I abide by that?” Shelley – who was bisexual – wrote love songs without gender. Bob Mould, of pioneering US band Hüsker Dü, and also a queer punk songwriter, was deeply influenced by Shelley’s “fast, short, catchy songs about sexual confusion”, and told me that hearing Buzzcocks was “an epiphany for me, for showing me the power of non-gender-specific love songs”.

Getting banned by the BBC wasn’t the worst thing

“Homosapien”, however, read like an assertion of Shelley’s queerness. “He wasn’t ever shy about his bisexuality,” remembers Headen. Shelley himself remembered that no one on the punk scene “seemed to bat an eyelid” that he was bisexual. Auntie Beeb, however, took exception to the song’s gay-coded lyrics, and banned it from the airwaves. “The 12in was being played in clubs,” remembers Headen, “but they told us it wasn’t going to get played on radio, and that screwed the single.”

“Typical BBC,” grins Russell, who was drumming on Shelley’s Homosapien tour when the ban hit. “But to be honest, if you wanted a hit, getting banned by the BBC wasn’t the worst thing. They banned Frankie Goes to Hollywood, too, and look at them.”

While “Homosapien” never enjoyed chart success like Frankie’s similarly outlawed “Relax” two years later, Russell performed the new material across Europe and the US, alongside Shelley, Buzzcocks’ bassist Steve Garvey – and “8-track tapes that contained the synths and the harmonies. It sounded great”. Until the band played the opening night of the new location of New York’s legendary Peppermint Lounge to an audience of mobsters and their wives. “They were still painting the venue as we walked onstage,” remembers Russell. “Then the tape machine failed and the backing vocals went slo-mo and out-of-key. It was horrendous. The mobsters were not pleased.”

Russell accompanied Shelley back to Genetic to help create his next solo LP, 1983’s similarly synthesised XL-1. Sessions were hard, as Rushent’s state-of-the-art synthesisers struggled to communicate with each other, but Russell remembers Shelley being at home among the tech. “He was a highly intelligent guy, and he saw this synthesiser stuff was the new cutting edge.”

XL-1 came accompanied by what was then ground-breaking computer software. Headen, who’d studied computers at university, at Shelley’s urging, stepped up to write a programme for Sir Clive Sinclair’s affordable new home computer, the ZX Spectrum, that screened the lyrics to each song, synchronised, with animations in the background. A feat of primitive software engineering, it was the product of hours and hours of programming by Headen. “It was rocket science then, but it’d be very simple now,” he remembers. “Pete was very involved; he and his boyfriend Francis suggested the graphics.” Shelley took great pride in XL-1’s ground-breaking bonus software. “He always said, ‘We invented karaoke!’,” nods Headen. “And, you know, there are lyrics on the screen, graphics, it’s all in sync with the music. It is karaoke!”

Rushent’s work on Homosapien saw him tapped to produce The Human League’s landmark 1981 album Dare, cementing his mastery of synth-pop. But Shelley released only one more solo album, 1986’s Heaven and Sea, before reforming Buzzcocks just in time for a new generation to discover his songbook. “Their dressing room after gigs was all famous people telling Pete, ‘I’m a huge fan’,” remembers Headen. “Whenever they played LA, Johnny Depp would have them play at [notorious Depp-owned LA club] the Viper Room. When they played in 1993, Kurt Cobain was there, and asked Pete to support them on their European tour for In Utero. That was one of the few tour laminates Pete kept. Kurt would ask Pete how he dealt with fame – Nirvana were the biggest band on the planet at that time. But after Kurt died, Pete just couldn’t talk about him.”

Buzzcocks continued to tour and record, until Shelley died of a suspected heart attack at his home in Estonia in December 2018. “I was in complete denial. I thought he must’ve faked it,” says Headen. “I didn’t believe it until Pete’s road manager came back from Estonia and said he’d seen Pete in the coffin.”

Shelley was only 63. But he’d lived long enough to see Homosapien reappraised and celebrated as an influence by artists like Detroit techno visionary Kevin Saunderson and LCD Soundsystem’s James Murphy, and to have Buzzcocks universally revered for his classic feel for melody and powerful songwriting. “Pete was perfectly happy with his legacy,” says Headen. “He’d say, ‘If I die tomorrow, I’m fine. I’ve done brilliant and everybody I want to recognise it recognises it.’ He loved what he did – he felt in complete control – and he affected a lot of people.”

Reissues of ‘Homosapien’ and ‘XL-1’ are available now from Domino

Bruce Springsteen joined by Paul McCartney at Liverpool concert: “Stuff of legends’

15 terrible movies directed by great actors, from Ryan Gosling to Johnny Depp

On ‘More’, Pulp pick up precisely where their imperial phase left off - review

Adam Duritz: ‘Kurt Cobain’s death scared me – it taught me what could happen to me’

Lord Woodbine: The forgotten sixth Beatle

The Lottery Winners: ‘Robbie Williams said to me, “Your biggest talent is bravery”’