Recently I moved from London to Berlin, a city with cinemas aplenty but, unfortunately for me, only a handful of films playing in English. While in the UK we are used to watching foreign films with subtitles, in Germany they are typically dubbed by voice actors, who even have their very own awards ceremony, described by Der Spiegel as “the Oscars of dubbing”.

As a non-German-speaking film lover living in Germany, I was feeling a bit like a zoo lion being fed couscous for dinner. So I conducted an experiment of sorts, to see whether today’s films would make sense without dialogue, and to gauge how much they rely on scripts to convey their message.

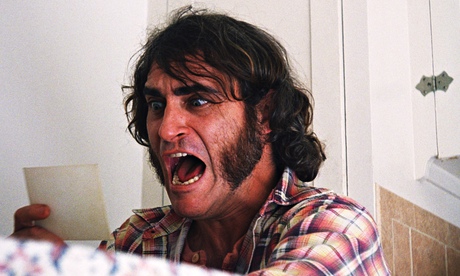

I chose four films I had never seen in English. I headed over to the the B-ware! cinema to watch the first, Inherent Vice, Paul Thomas Anderson’s sleuth flick, with Joaquin Phoenix playing a sort of dim-witted Hunter S Thompson, but speaking in a gravelly German.

Inherent Vice is notorious for its labyrinthine plot, but for a PTA film, it also turns out to be surprisingly slapstick. It’s numerous dirty jokes – including one running gag about a police chief and his chocolate bananas – needed no translation. For a while, as it seemed to use the familiar plot devices of a detective story, I just about kept pace with it. But soon enough, I had to resort to watching through the filter of other audience members, whose fidgety demeanour indicated that they were just as stumped as I was.

So far, not so good.

At a multiplex on the highest floor of a shopping arcade, I went to see robo-themed blockbuster Chappie. I was alone in a 100-plus-seater auditorium: an eerie experience which I don’t recommend. Hand on heart, I can say I understood the entirety of this film – but given that it deals with the complex subject of artificial intelligence, I rather think I shouldn’t have been able to. As with many films you might see at the multiplex, a Hans Zimmer soundtrack does most of the work of telling the audience what to think. That isn’t to say this wasn’t a highly entertaining, even revelatory experience. Minus the cheesy dialogue, a cheesy blockbuster turns into something far grander and more sweeping, almost like opera.

To appreciate just how tricky dubbing is, you have to see it done badly – as I did when I went to see Selma. In all fairness, it is a very speech-heavy film, which makes it harder to dub, and Martin Luther King’s vocal cadences are so well known that his German stand-in was never going to be absolutely convincing. Even so, the sync here was noticeably out of kilter, and it shattered any suspension of disbelief. Of course, a lot of the film features scenes of civil rights leaders talking tactics, but for all I knew, they may as well have been chatting about the weather or the contents of their breakfast.

But there were also moments of visual genius, including one memorable scene in which King sits in a darkened prison cell after his arrest, and a glimmer of light shines in, haloing just the tip of his left ear. Tension, pain and hope were all projected here without a word.

I go back to the B-Ware! cinema, and it is fair to say that the guy selling tickets is puzzled by my enthusiasm for seeing films in a language I’m clearly incapable of understanding. I’m here to see Roy Andersson’s final instalment of his “living” trilogy, the sumptuously titled A Pigeon Sat on a Branch Reflecting on Existence. It was dubbed from Swedish into German and, while I’m sure I would have picked up on the finer points had there been subtitles, I came away with a clear vision of the director’s world: a place populated by sleepwalkers and lovable fools who really don’t have the first idea about anything.

How did this eccentric director infiltrate my brain so vividly without the use of words? Andersson has said in an interview that he didn’t want a single frame in his movie that was indifferent, and this obsessiveness shows. Long, motionless takes allow the audience to unravel the many layers behind each shot. Occasionally, there is a scene without words or recognisable characters, and which doesn’t further the plot. A man with downcast features stares out of a window smoking; he might just have received some bad news, we don’t know. His lover walks up to him, she grabs his arm and looks towards him. Cut.

This kind of cinema communicates feelings with the universal language of music and images and, unlike a film such as Chappie, doesn’t rely on the audience having felt that particular thing before. Arguably, this is the essence of cinema.