PRODUCER WEEK 2025: The 1960s were a decade of quite astonishing change. The conservatism and austerity of the postwar period was besieged by the blooming of pop culture - and a new era of self-expression began to flower in the heads of a generation.

By 1966, culture, fashion, art and comedy were undergoing a giddy renaissance, yet it was pop music that was the prime mover. Its influence over the youth now solidified, pop could push beyond its hormone-fuelled bedrock. It was increasingly wandering into new frontiers of possibility.

Nothing exemplified this as clearly as the sonic evolution of the Beatles.

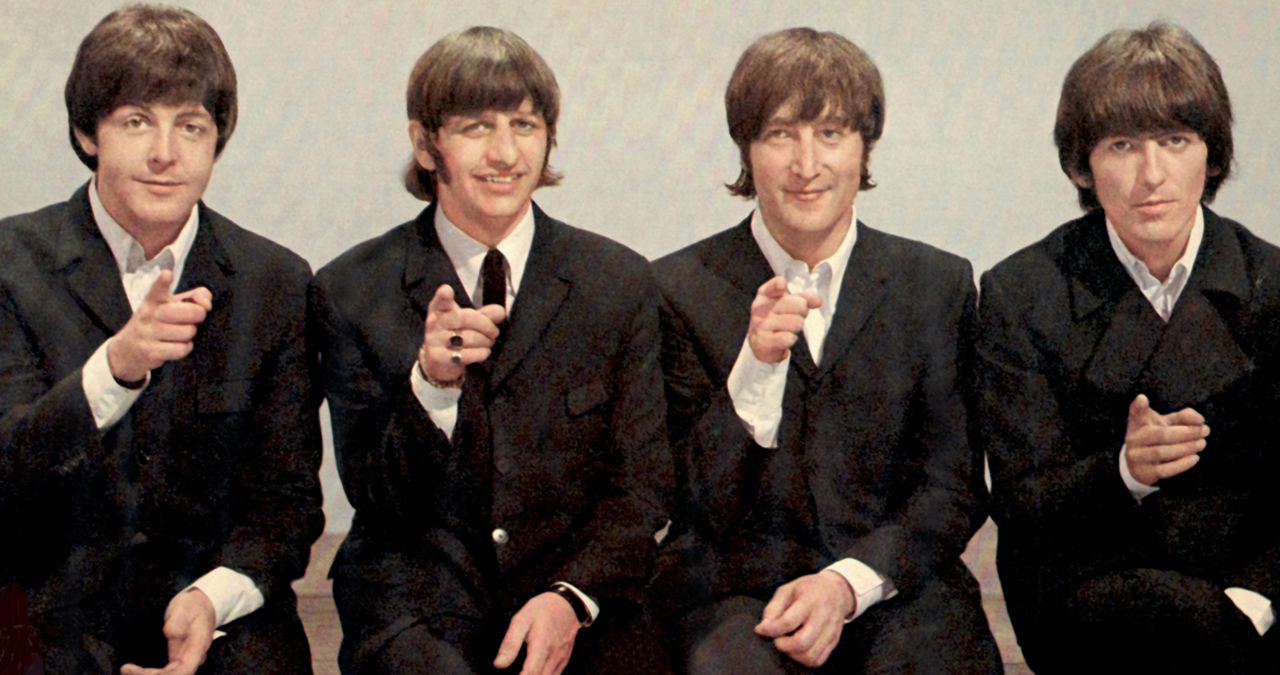

Since their explosion into the public consciousness a scant three years earlier, the Fab Four had demonstrated an aptitude for pop songwriting.

Now, curiosity - and competition - had spurred them to deviate away from the thematic norms of pop songwriting (i.e. love, relationships and relentless positivity).

On their sixth studio album, Rubber Soul in 1965, John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Ringo Starr had widened their musical scope significantly. Edging away from the dictates of pop commerce, Rubber Soul rippled with more mature themes - and a more varied instrumental palette.

But it was 1966’s Revolver that really instigated the Beatles’ pioneering second stage.

One track in particular is undoubtedly a firm contender for being the most groundbreaking in the history of recorded music.

Tomorrow Never Knows was the very first track to be cut for the album, and contained multitudes of technical innovations. It sounded unlike anything anyone had ever heard before. And yet, it resonated with the era perfectly.

Surrendering to the void

Accompanying their desire to be more creatively ambitious, the heavy demands of touring internationally had also started to take their toll on the four young men, then still in their mid-twenties.

While by 1965, the Beatles were regularly filling out football and baseball stadiums in the US, the increased stress of the security implications, a gruelling schedule and sheer volume of their often-hysterical audiences led to increased dissatisfaction.

Behind the closed doors of their studio, Abbey Road (then known as EMI Recording Studios), the Beatles found a safe haven. It was calm, secure ground on which they could focus on their core passion with freedom and support.

Inspired by the politically-charged and self-reflective writing of Bob Dylan, the neo-philosophy of the fomenting acid culture and the unbridled sonic adventurousness of the Beach Boys, the Beatles were driven to challenge themselves as songwriters.

Partly excited by the potential of the studio, the group were also wary of being left behind as pop’s inexorable pace quickened. They wanted to be taken more seriously as artists, as opposed to the conveyors of pop confectionary that some more 'cerebral' commentators regarded them as.

Revolver demolished the notion that the Beatles were a passing fad. It re-framed them as music’s most intrepid pioneers, while at the same time, the biggest entertainment fixture on the planet.

An impressive balance that nobody has yet been able to match.

Revolver’s final track was recorded first, and was borne out of a particularly strange starting point.

Originally dubbed ‘Mark 1’ and later ‘The Void’ - Tomorrow Never Knows was inspired by Lennon’s mind-expanding perusal of psychedelic drug advocate Timothy Leary’s ‘The Psychedelic Experience: A Manual Based on the Tibetan Book of the Dead’.

An attempt to transcend the physical world and unlock the potential of the mind, Lennon was in thrall to Leary’s trendy, acid-centered teachings.

“[Timothy] Leary was the one who was going round saying, 'Take it, take it, take it,' and we followed his instructions in The Book of the Dead, his how-to-take-a-trip book,” Lennon told Hunter Davies in his 1968 authorised biography.

“I did it just like he said in the book, and then I wrote 'Tomorrow Never Knows,' which is almost the first acid song, 'Lay down all thought, surrender to the void’.”

While the obvious acid-infused subtext was a pretty provocative theme, it was the attempt to musically mould Lennon’s psychedelically inspired concept into a listenable form that would prove a head-scratcher.

But realising his vision would usher in several innovations that are now studio production norms.

Convening at Abbey Road to begin making Tomorrow Never Knows at 8pm on April 6th 1966, the foundations of the track were - as Paul recalled in the Beatles Anthology - Lennon strumming ‘rather earnestly’ on the chord of C while he reeled off his mantra-like lyric.

This modal nucleus underlined the Eastern-influenced form he wanted the track to reflect.

Coupled with the Beatles’ desire to expand, there was also a serendipitous changing of personnel at Abbey Road itself.

Replacing outgoing head engineer Norman Smith came Geoff Emerick. The 20 year-old junior engineer had been in their producer George Martin’s team since 1964, so knew the boys well.

Suddenly promoted to chief engineer at a time when the Beatles’ demands were becoming increasingly more unconventional, Emerick - then younger than the Beatles - was thrilled by the challenges coming his way, and was just as buoyed by the potential of the recording studio.

"We didn't have loops in those days. Your dad had a great time!"

Critical to Tomorrow Never Knows’ sound was its underlying rhythmic throb, supplied by Ringo Starr’s relentless, drum loop-like pattern. The sound of which was carefully wrangled by Emerick and Starr.

Many now-norms of drum recording were first put to use during the making of this track.

A key one was the damping (and close-mic’ing and compression) of the 22-inch bass drum of Starr’s Ludwig Black Oyster Pearl kit.

“There was this woollen sweater with four necks that they had received from a fan,” Emerick told Andy Babuik in The Beatles Gear.

“It was around the studio, so I stuffed it into the bass drum to deaden the sound. I moved the bass drum microphone very close to the drum itself, which really wasn’t considered the thing to do at the time. We then ran the kit sound through a Fairchild 660 valve compressor.”

The resulting brilliance, definition and oomph of the sound resulted in the close-mic’ing of a dampened bass drum to become a standard practice from this moment on.

Using AKG D19C mics for the drum overheads and an AKG D20 for that ingenious bass drum capture, Emerick and Starr’s kit-recording fastidiousness (which also found Starr balancing a cigarette packet atop his snare to reign in its resonances) resulted in the perfect central pulse for the track.

The sound - and style of Starr’s repeating drum pattern - would prove influential for decades to come. It foreshadowed the structural centrality of drum loops in dance music years later, while its tight repetitiveness prefigured the era of sample-based production.

Although of course, Ringo wasn’t actually playing a loop - he had to lock into that groove for duration of the track’s runtime.

Years later, in a 2015 interview with Paul Zollo, Starr recalled that his son - upon first hearing the track - believed it to be a drum loop; “Zak, years and years ago said ‘Oh, and that loop you had.’ And I said ‘Loop?’ Loops?!,” remembered Ringo.

“I said ‘Phone this number,’ and he phoned the number, and George Martin said ‘Yes?’ Zak went ‘Well, is that a loop?’ and George Martin had to tell my boy, ’Look Zak, we didn’t have loops in those days. Your dad had a great time!’”

Ringo’s contribution to the track went beyond that iconic drum part.

As with A Hard Day’s Night and Eight Days a Week, the title - Tomorrow Never Knows - stemmed from another of his wry malapropisms.

The original uttering of the phrase happened during an interview in 1964 in response to a journalist asking him about his hair being surreptitiously cut at the British Embassy during their first US visit.

Lennon thought it struck the right balance of profound and playful to mask the track’s heavier subtext.

Locking in with Starr’s beat, McCartney’s bass part was (unusually for him) static and grounded.

Fastening his Rickenbacker 4001S bass to the note of C in ostinato form, McCartney supplied a steady palpitation that tightly latched to Starr’s drum part, providing a neat bedrock for the more extraordinary additions that were to follow

"They probably thought we were daft"

With the rhythm section in-place, the real magic of Tomorrow Never Knows had a springboard from which to launch.

Bolstering the track’s C-note drone was a Hammond organ. Its sustained chord sound was output through a Leslie speaker cabinet, cradling the musical information in pad-like form.

But it was the decision to incorporate tape loops into the mix - a suggestion of Paul McCartney - that elevated the track into a new domain.

McCartney had, on the quiet, been an avid tape-loop experimentalist.

He remembered years later that his interest in the field had tended to be overshadowed by Lennon’s prominence on the band’s more outré tracks; "What's often said of me is that I'm the guy who wrote 'Yesterday’,” Paul told Wired in 2011. “But I'm also a guy who was really interested in tape loops, electronics and avant-garde music. That just doesn't get out there on a wide level.”

For Tomorrow Never Knows, there were five main loops, all of which had been stretched or manipulated in some way.

Firstly there was a seagull-like sound that appears near the track’s beginning and conclusion. This chirpy effect was actually a recording of McCartney’s own laughter, sped up to emulate a joyous bird in flight.

Then there were some reversed and looped strings in B flat major (which, when played over the C, gave an impression of polytonality).

There was the sound of a mellotron on its ‘Flute’ setting and another on its ‘Strings’ setting, as well as a recording a the sitar-type sound - actually a tamboura - that opens the track, which played an ascending phrase.

Output via five BTR 3 tape machines, these carefully selected loops were each hand-operated by an individual technician.

Taking their cues from the musique concrète approaches of visionaries like Karlheinz Stockhausen, the Beatles had the idea to live-mix and essentially ‘perform’ these samples during the final mix of the track

The ever-enthused Emerick gleefully took to the task of setting this up.

As he remembered in his extraordinary memoir, Here, There and Everywhere, “What followed next was a scene that could have come out of a science fiction movie - or a Monty Python sketch.

"Every tape machine in every studio was commandeered and every available EMI employee was given the task of holding a pencil or drinking glass to give the loops the proper tensioning. In many instances, this meant they had to be standing out in the hallway, looking quite sheepish.

"Most of those people didn’t have a clue what we were doing; they probably thought we were daft.”

Emerick and Martin rode the faders in the studio, with the Beatles barking instructions as to which tape loops should be raised and lowered.

"With each fader carrying a different loop, the mixing desk acted like a synthesizer,” Emerick recalled in Here, There and Everywhere. “We played it like a musical instrument, too, carefully overdubbing textures to the prerecorded backing track.”

This out-there approach to manipulating disparate sound sources was way ahead of its time, and - being that it was tracked and manipulated live - was impossible to reproduce afterwards. But the resulting tape-mix was burnt into the final version of Tomorrow Never Knows forever.

Complementing these loops, a zig-zagging guitar line from Harrison was injected into the mix, but to match the track’s vortex-like arrangement, it was reversed.

The idea of backwards guitar solos had first arisen during the recording of another Revolver standout, I’m Only Sleeping, when - accidentally - the tape had been loaded incorrectly into a tape machine and produced a suitably yawning-esque sound.

Backwards guitar was suddenly a creative texture that the Beatles could draw on.

Within Tomorrow Never Knows, George’s guitar part (which was played on an Epiphone Casino routed through a Leslie cabinet) gave the impression of a winding shimmering entity, coiling into itself.

It was the aural equivalent of bending time and space.

"It's the Dalai Lennon!"

While its sonics were certainly unlike anything heard before, at the heart of Tomorrow Never Knows was Lennon’s prophet-like vocal, instructing listeners to surrender to the void and open their minds to a new universe beyond our perception.

Lennon conceived of a vocal that sounded as profound as its lyric, wanting the characteristics of a monk chanting atop a mountain. He proposed quite an outlandish idea for capturing the right kind of vocal quality he was imagining.

“He suggested we suspend him from a rope in the middle of the studio ceiling, put a mike in the middle of the floor, give him a push and he’d sing as he went around and around,” Geoff recalled in The Beatles Recording Sessions.

Instead of this potentially dangerous idea, Emerick pondered a more down-to-earth solution.

As he recalled in his autobiography; “The studio’s Hammond organ was hooked up to a system called a Leslie - a large wooden box that contained an amp and two sets of revolving speakers, one that carried low bass frequencies and the other that carried high treble frequencies; it was the effect of those spinning speakers that was largely responsible for the characteristic Hammond organ sound.”

Geoff had the - then-radical - idea to route the vocal signal through the Leslie.

“In my mind, I could almost hear what John’s voice might sound like if it were coming from a Leslie. It would take a little time to set up, but I thought it might just give him what he was after.”

Patching in the signal, Emerick then committed the audio of the mic’d-up Leslie cabinet to tape, and created an effected version of Lennon’s vocal that sounded suitably supernatural.

“Lennon’s voice sounded like it never had before, eerily disconnected, distant yet compelling,” recalled Emerick. “The effect seemed to perfectly complement the esoteric lyrics he was chanting. Everyone in the control room - including George Harrison - looked stunned."

Geoff continues, “Through the glass we could see John begin smiling. At the end of the first verse, he gave an exuberant thumbs-up and McCartney and Harrison began slapping each other on the back.

"’It’s the Dalai Lennon!’ Paul shouted.”

Tomorrow Never Knows’ successful Leslie experiment prefigured the solidification of ADT (Automatic Double Tracking) later in the Revolver sessions, though the track itself didn’t feature it.

The end of the beginning

So, let’s run those innovations back shall we?

Tomorrow Never Knows was the first significant pop track to feature a tightly compressed, dampened bass drum, it was the first to incorporate a hand-manipulated tape loop collage, triggered at random and in a performative-manner in the studio.

It was among the first Beatle tracks to sport backwards guitar, the first to feature an unheard-of vocal-doubling and effecting process (laying the groundwork for the advent of Automatic Double Tracking later in the album sessions - another future fixture) and the first British pop track to orient itself around a non-Western musical form.

That's quite the forward-thinking production process. It'd be one that’d be worth talking about, even if the results were less than spellbinding.

Thankfully, the song was - and remains - one of the Beatles' most cherished accomplishments.

Tomorrow Never Knows was a veritable atom bomb of possibility.

It exploded a twin revolution in the minds of listeners. It showed that pop music could be a bigger, bolder and more bountiful thing than previously imagined.

In the hands of the Beatles, pop could be existential.

Now with a thematically and musically boundless playing field, the potential for pop’s vibrant future was revealed.

Critically (particularly for us at MusicRadar) the track was arguably the first major example of an artist approaching the the studio as an instrument.

Aiming to reflect a whirlwind, transcendent experience through sound, the Beatles, Geoff Emerick and George Martin, unlocked techniques and approaches that are now foundational to how we approach music production.

Ironically, considering it triggered many of the album’s most colourful ideas, Tomorrow Never Knows was sequenced as Revolver’s concluding number.

The highest summit of the record also proved a compelling teaser for one of the most extraordinary creative outpourings in pop history.

It was right around the corner…