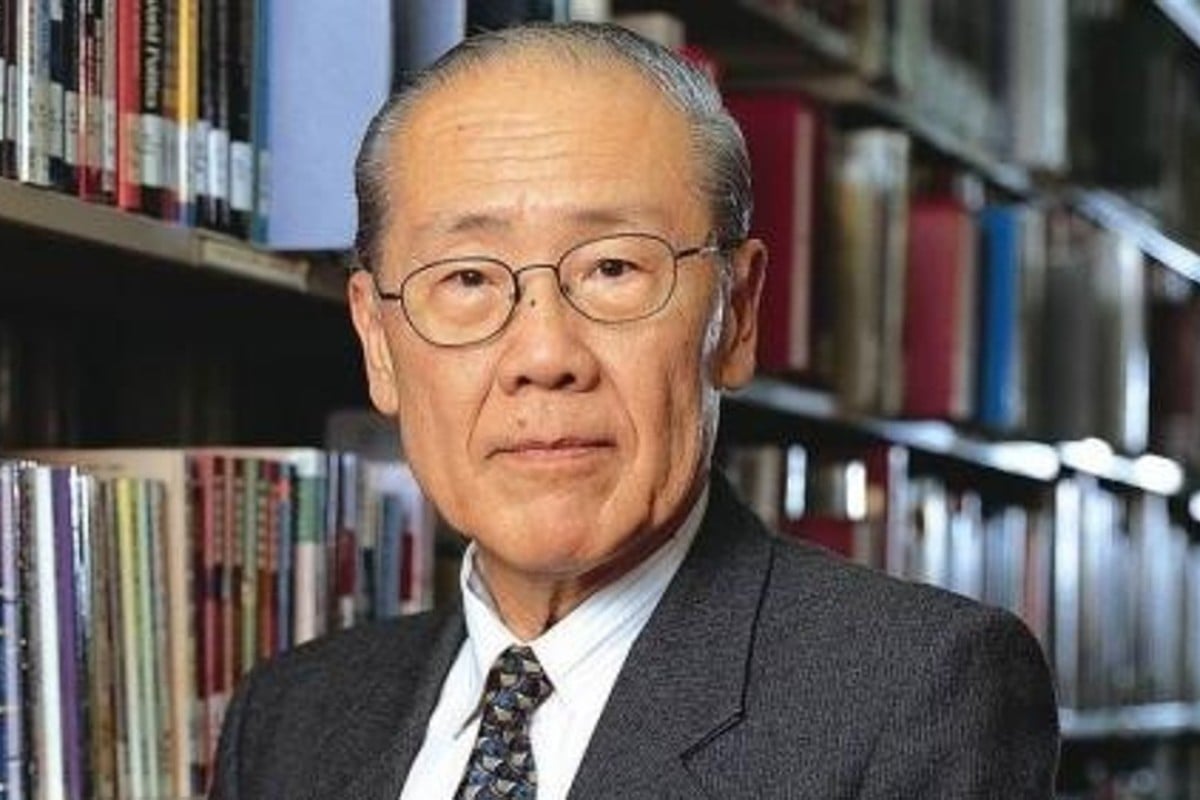

When the 2018 Queen’s Birthday Honours list recognised Wang Gungwu for his services to Australia-Asia relations, the eminent historian responded with typical grace – even if some attached an air of sadness to that which he left unsaid.

“It is an honour. Australia from the 1960s to the 1980s led the Western world in its keenness to understand the new Asia. I was privileged to be among those who tried to make that wish come true. It was a most exciting time,” Wang told the National University of Singapore (NUS) newsletter on receiving the honour in June.

Sun Yat-sen to Mao Zedong, I watched a new China being reborn: the Wang Gungwu memoir

This was Wang, the consummate scholar and educator, the ultimate Nanyang junzi (gentleman), speaking. A man who, even as one of the world’s foremost experts on the Chinese diaspora, could summon enough diplomacy not to mention the decline of Asian studies in Australia in the decades since – a decline that has caused great sadness in the academic world.

Diplomacy comes naturally to Wang, as is clear from the memoir of his youth Home is Not Here, which he is publishing at the grand age of 87. As the memoir makes clear, Wang – a professor at NUS, a former vice chancellor of the University of Hong Kong and emeritus professor at the Australian National University – benefited from his early years growing up in a multicultural, immigrant family. Wang’s early life was marked by the crossing of borders, something that was to have a profound impact on his later outlook and academic career.

He was born in Surabaya, Indonesia, on October 9, 1930, but from the age of 2 was raised in Ipoh, Malaysia. He went through the English-medium education system but acquired a strong grounding in Chinese classics and history under the watch of his father Wang Fo Wen, a federal inspector of Chinese schools in Kuala Lumpur before he retired to become principal of a Chinese high school in Johor Bahru.

In 1947, Wang’s family sent him to China for undergraduate studies at the National Central University in Nanjing, though with the Chinese civil war reaching its conclusion he was forced to return a year later. He went on to complete his Bachelor of Arts degree in 1953 at the University of Malaya, then located in Singapore, with a thesis on the role played by exiled Chinese reformists and revolutionaries in the British Straits Settlements.

West’s hottest intellectual Jordan Peterson: psychology’s Trump?

He stayed on and obtained a master’s degree in history in 1955 with a study on early Chinese trade in the South China Sea, long before the body of water gained infamy in international relations. Two years later, at the School of Oriental and African Studies at the University of London, he secured his PhD in Chinese history, basing his doctorate on a new interpretation of the power structure of the Five Dynasties of 10th Century China. It contested the traditional wisdom that the Song dynasty had been a clean break from the Tang dynasty and argued that most political innovations had in fact emerged during the brief period between them.

This sojourner background and broad liberal educational experience shaped the researcher Wang was to become.

He was Southeast Asian, yet quietly and resolutely Chinese. A linguist who had command of English, Chinese, Malay, Hakka and Cantonese. His home discipline was history, but he was an early advocate of the inter-disciplinary approach. He was one of the great historians of Chinese overseas, but one who paid great attention to the history of China itself.

Indeed, he used this two-pronged approach of “inside and outside China” to lead the scholarly world into probing the dynamics of maritime commerce, migratory flows, power relations, cultural make-up and identity politics in the region. Along the way he shared provocative views on the use of history as a tool for nation-building, the implications of a resurgent China, the rise of nationalism among Chinese youth, and the need for patience in waiting for democracy in Hong Kong. He also warned of empire-building in Southeast Asia by larger states.

His career in academia began in 1957 at the University of Malaya, where he rose to head the history department. A long stint at ANU followed before he went to Hong Kong in 1986 to take up the post of vice chancellor/president, a position he held until 1995 and which coincided with an exceptionally turbulent period as the British colony prepared for the handover.

Aamir Khan: the second coming of Tagore?

In 1996, Wang returned to Singapore to lead and transform the Institute of East Asian Political Economy into the East Asian Institute. It was not an easy decision as there was an underlying tension between him and the Singapore political leadership under Lee Kuan Yew that could be traced back to their British university days. But his Singapore-Malaysia roots, the preferences of his wife Margaret and the persuasive power of his friend Goh Keng Swee all played a part in convincing him to take the opportunity.

Taking university administrative roles might have been time-consuming, but Wang cherished the principle of academic institutions being administered by scholars rather than government bureaucrats. His profile as a public intellectual – rather than one in an ivory tower – was in keeping with the intellectual tradition of the intelligentsia in China.

As an undergraduate, he dipped into the student activism of the 1950s, becoming the first president of the left-wing University Socialist Club and a writer of poetry and fiction for student publications. Later, as an academic, he would edit journals and promote talks for the South Seas Society, the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society and the Singapore Society of Asian Studies.

Taking up the clarion call for post-second world war nation-building and for cultivating a Malayan identity, he led a review of the curriculum at Nanyang University in 1965, a controversial matter that provoked a fierce round of student protests.

That abortive review and negative public reactions that coincided with the political separation of Singapore from Malaysia put a dampener on Wang’s activism, if only briefly.

Thereafter, he gave his support to the founding in 1968 of a new Malaysian multi-ethnic political party, the Gerakan Ra’ayat (People’s Movement) and, when in Australia, marched in the anti-Vietnam War protests and from the late 1970s helped government agencies forge a new relationship with China as the communist nation began its reform and opening up. In Hong Kong, he became a notable voice in the debate surrounding the colony’s return to China.

In the second half of the 1990s, after his “homecoming” to Singapore, he helped shape several new public institutions such as the Sun Yat Sen Nanyang Memorial Hall, the Chinese Heritage Centre, and the Hua-Song Museum.

Singapore can count itself lucky to have Wang return home for the final stretch of his academic life. His legacy of groundbreaking scholarship will remain an affirming presence on campus for many years to come. Through his writings, teachings and informal mentoring he has moulded a new generation of scholars not only in the Asia-Pacific, but across the world. ■

Huang Jianli is Associate Professor in the History Department of the National University of Singapore. ‘Home is Not Here’ is already in bookshops in Singapore and Malaysia, and will be available in Hong Kong from early September. It can be pre-ordered in North America from University of Chicago Press