When it comes to racing on the Angliru - an ascent so hard it has often proved more than capable of deciding the overall outcome of the Vuelta a España, and which could well do so again on this Friday's stage 13 - literally nothing is set in stone, and that's true both for a climber as accomplished as Vuelta leader Jonas Vingegaard, and certainly for the rest of his GC rivals.

Given how important a role on which the Altu de L'Angliru, to give it its full name, has taken in the Vuelta, it's striking how recently the Angliru was first used with a win for the late José María Jiménez, back in 1999. Before that, it had never appeared in any race, let alone the Vuelta.

Other climbs all have much longer-established roles in the race's history, like the nearby, fearsomely-difficult Alto de Covadonga - almost as well-known for being home to some of the last wolves in western Europe as it is for its role in the Vuelta - and the equally close Alto del Naranco in Oviedo or the Sierra Nevada in southern Spain. But in a comparatively short space of time, the Angliru has managed to carve out an even more special place in the hearts of many of Spain's cycling fans than many of its better known, earlier, ascents.

That's partly because the Asturian mountain's extreme difficulty makes it one of the most demanding of judges anywhere in the world of climbing form. And that very same toughness also means that the Angliru is invariably one of the most unpredictable and exciting days of any Vuelta.

"I think tomorrow [Friday] is going to be one of the most important GC days. It's a very tough climb and there is nowhere to hide," Vingegaard said in his usual leader's press conference following stage 12. "You have to give everything you can, it's absolutely iconic."

In the 2025 edition of the Vuelta, it's fair to say that the Angliru marks the perfect place for a climber like Vingegaard to stamp his authority on the race and take a definitive lead overall. But Vingegaard will also only really know if he can win the Vuelta if he comes through that climb with his advantage intact or, he hopes, seriously increased.

However, what is certain is that the Angliru's difficulty is such that nobody, not even Vingegaard, can be sure of how it will play out: hence the interest of Friday's stage 13.

A climb that marks you

“The Angliru is a climb that marks you, but in my case in a good way, it’s my favourite climb of the whole Vuelta,” four-times overall winner Robert Heras, who holds the record for the ascent at 41:55, told Cyclingnews a few years back.

“I went up there four times in the Vuelta and it’s not just a special ascent because of its difficulty. It’s also one where you can create big differences on your rivals, ones which can change the course of the race.”

It’s true that actual victory in the Angliru is far from certain to guarantee an overall triumph in Madrid. Only once in the last eight ascents, in 2008 with Alberto Contador, has the Vuelta’s stage winner on the Angliru also won the race outright.

However, the Angliru has seen the race lead change four times: in 2002 Heras replaced Oscar Sevilla atop the GC; in 2008 Contador ousted Egoi Martinez; in 2011, Juan Jose Cobo, albeit prior to disqualification, supplanted Sky’s Bradley Wiggins; and in 2020, Richard Carapaz briefly squeezed out Primož Roglič from the top spot overall.

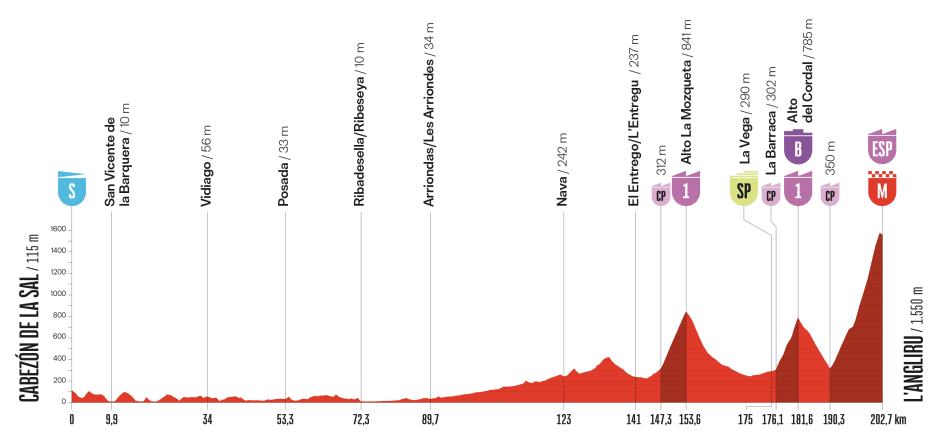

What is radically different from the previous ascents of the Angliru compared to many of the the previous eight is that this year's stage also contains one of the longest approach paths to the climb itself. Stage 13 is 203 kilometres long in total, 68.5 kilometres longer than in 2023 and 94 kilometres longer than in 2020.

Although much of the approach route is a rolling, picturesque ride along the coast of Cantabria, stage 13 also contains two hefty previous climbs to the Angliru, just like in 2023: the Alto de la Mozqueta and the Alto del Cordal.

Both of these climbs, ranked category 1, are very typical of the mountains of inland Asturias: relentlessly steep, zigzagging up through woodland and (in the case of the Cordal) a narrow, nominally two-lane, badly surfaced road. The descent off the Cordal, often used by the Vuelta to reach the Angliru, is notoriously technical, too and has seen some bad crashes in the past: the most notious was when race leader Abraham Olano cracked a rib there in 1999, finally losing the overall as a result of his injury.

Fortunately, though, the weather is currently set to continue to be dry throughout the day, so the odds are the front segment of the peloton will still be all together, albeit strung out by the descent, when it reaches the foot of the Angliru.

The Goats' track

And then what? The first 5.5 kilometres are not so hard, but from that point onwards, on ramps known as the Viapará, the road rears more steeply and the average gradient shifts to 10.1%. On such steep slopes, the stage switches from being a normal race into the toughest of uphill individual time trials.

Hard as 10% may sound, on the Angliru those are the easy parts, with mid-climb challenges like the Cuesta les Cabanes ramp, at 21.5% pushing the riders into the reddest of red zones.

There is a brief respite of sorts at kilometre 8.5, where the ramp’s percentage points drop to a mere 14.5%. But then as the race swings right for another kilometre-long straightaway, we’re back up to a more standard, horrendously hard, 20%.

Could it get any worse? Of course it could, this is the Angliru. With just 2.5 kilometres left to go, the steepest corner of the entire climb, so well-known it actually has a name - Curva de los Cobayos or the improbably named ‘guineapigs' corner’ - leads directly onto the 1.3km-long segment called Cueña les Cabres, translated as "the goats’ track", as it is rather more aptly called.

By far the hardest part of the Angliru, with an average of 18% and the toughest segment at 23.5%, the Cueña les Cabres is where the massed lines of fans traditionally gather, where team and media car clutches burn out, where riders suddenly reach the end of their strength and where, perhaps, the Vuelta may be won or lost.

The last part of the climb maintains the pain, with the final hard segment of El Aviru, which has slopes of 21% and 1.5km to go, very likely to broaden any gains made by a breakaway on the Cabres ‘ramp’. Finally, after a short descent and quick kick back up in the final kilometre to the Picu del Puerto finish, the ascent is over: 1,266 metres of vertical climbing to 1,573 metres above sea level.

How key is teamwork?

It’s often remarked on such ultra-steep climbs that teamwork is virtually impossible and the race becomes much more of a hand-to-hand struggle between individual riders. Heras only partly agrees, though.

“The thing is that the Angliru is actually two climbs, as the first five kilometres or so are not that hard," Heras said.

“In that part, teamwork is really important for wearing down the rivals. But then in the second half, the worst thing is that the steepness never really eases at any point, and there’s nowhere that you can get even a moment to catch your breath.

“That said, even if you can’t follow somebody’s wheel, having a teammate with you if possible is important at that point, because it it acts as psychological support.”

For Vingegaard, currently with an advantage of 50 seconds over closest rival João Almeida (UAE Team Emirates-XRG), the Angliru is his first real opportunity to turn that advantage into minutes.

However, the minor questionmark regarding his condition following Tom Pidcock's (Q36.5 Pro Cycling) ability to gap him briefly on the Alto del Pike on stage 11 on Wednesday, rendering an even more unpredictable climb yet more intriguing for the fans - and Vingegaard himself.

The Dane does have good memories of the Angliru, though, to keep him motivated. In 2020 on his frst ascent he was instrumental in keeping then teammate Primož Roglič up there with the favourites. Then in 2023, when Roglič and he finished together in first and second, respectively, at the summit of the Angliru, the main challenge of the day came after the ascent, not on it - given the controversy that erupted over how he and Roglič had both left Visma teammate and leader Sepp Kuss trailing on the Angliru itself.

Asked on Thursday whether he had anticipated coming into the Angliru with his current advantage on Almeida, Vingegaard said things were already going better than expected. However, that didn't mean he wasn't interested in making the most a chance like the Angliru to potentially inflict more damage, either.

"To be honest, our initial plan in the Vuelta was to ride pretty defensively, so to have two stage wins and the advantage I have already after two weeks is a super nice feeling.

"So far, though, the finishing climbs on the race have been fairly straightforward. But tomorrow [Friday] is another story."

Subscribe to Cyclingnews for unlimited access to our 2025 Vuelta a España coverage. Our team of journalists are on the ground from the Italian Gran Partida through to Madrid, bringing you breaking news, analysis, and more, from every stage of the Grand Tour as it happens. Find out more.

Climbs

- Alto La Mozqueta (cat. 1), km. 153.6

- Alto del Cordal (cat. 1), km. 181.6 - time bonus

- L'Angliru (Esp) km. 202.7

Sprints

- La Vega, km. 175