Ancient volcanic heat may have shaped the moon from the inside out, keeping one side thinner, warmer and more geologically active than the other, a new study suggests.

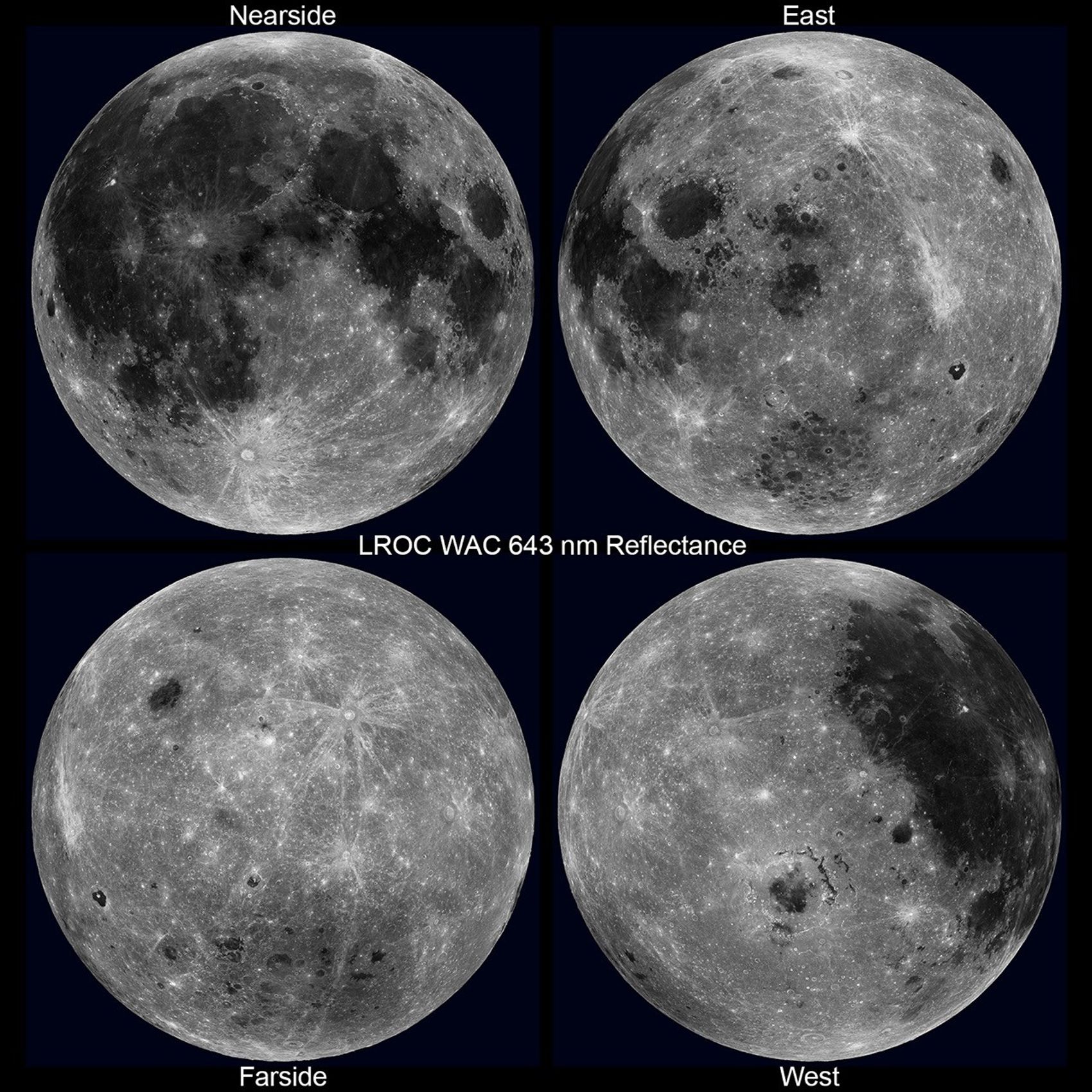

The moon's nearside is scarred by massive impact basins, while its farside features far fewer and smaller basins, and a significantly thicker crust — an imbalance that has puzzled scientists for decades. Over the years, researchers have proposed various theories to explain this asymmetry, ranging from tidal heating caused by the moon's orbit around Earth to a giant early collision that reshaped its internal structure. But there has been no clear evidence pointing to a mechanism capable of driving such uneven evolution, perhaps until now.

A team of scientists analyzing data from NASA's GRAIL mission has identified the first clear signs of temperature differences deep within the moon. The study suggests heat-producing elements lingering in the moon's crust have kept one side of the moon thinner — and warmer — than the other, even after billions of years.

The disparity was so striking, "it stood out in the data and persisted through multiple checks and alternative analyses," Ryan Park, a senior research scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, who led the study, told Space.com. "Our team was genuinely puzzled."

Evidence for this asymmetry comes from data collected by NASA's GRAIL mission, which in 2012 used a pair of spacecraft to map the moon's gravity with remarkable precision. By tracking tiny shifts in the distance between the two orbiters as they flew around the moon, Park and his colleagues were able to detect subtle variations in its gravitational pull — differences linked to uneven structures deep beneath the lunar surface.

"Our study delivers the most detailed and accurate gravitational map of the moon to date," Park said. This map also lays the groundwork for developing a navigation system that will improve the safety and reliability of future lunar missions, he added.

Studying this data, the researchers found a 2–3% difference in how the moon's mantle deforms between its near and far sides. Computer simulations of the moon's structure suggest this difference can be attributed to a temperature gap of 212-392 degrees Fahrenheit (100-200 degrees Celsius) between the nearside and farside hemispheres, with the nearside being warmer, according to the new study.

This contrast has likely been sustained by a higher concentration of radioactive elements on the moon's nearside, which are remnants of volcanic activity from 3 billion to 4 billion years ago, the new study suggests. Indeed, data from NASA's Lunar Prospector mission revealed the lunar nearside contains up to 10 times more thorium than lunar farside.

The abundance of thorium and similar radioactive elements would have generated additional heat, driving temperature differences of several hundred degrees throughout the nearside mantle during the moon's early history. This heat could have created large pockets of molten rock, helping shape volcanic features, such as lunar maria, we see today.

"We suggest that the processes which formed the lunar maria several billion years ago are still present and active today," Park said.

Missions like GRAIL that measure how a planet's gravity field changes as a spacecraft orbits allow scientists to gain valuable clues about the internal characteristics of planetary bodies from afar. Because this technique does not require a spacecraft to land on the surface, it can more easily reveal interior structures of worlds like Mars, Saturn's moon Enceladus, or Jupiter’s moon Ganymede, the researchers say.

"These measurements are especially valuable for worlds where surface exploration is difficult or impossible," Park said.

The team's findings were published on Tuesday (May 14) in the journal Nature.