In Lower Saxony, in 2022, a wolf attacked and killed Dolly, Ursula von der Leyen’s favourite pony. Strategically, this was a terribly poor move on the wolf’s part. The president of the European Commission is a passionate equestrian. Citing “numerous reports of wolf attacks on animals” and an unsubstantiated “increased risk to local people”, Von der Leyen requested an in-depth analysis into the wolf’s status in Europe. On the basis of that analysis, the European Commission voted last year to downgrade the wolf’s level of protection, and on Monday, that directive formally entered into force. With it began a whole new chapter in our relationship with the wolf.

Wolves have been undergoing a remarkable resurgence. By the mid-20th century, they had been pushed almost to extinction in Europe, but a combination of EU conservation measures and the abandonment of agricultural land means that today there are more than 23,000 across the continent, a species of least concern. In a biodiversity crisis, it is heartening to see nature’s capacity to heal if we let it.

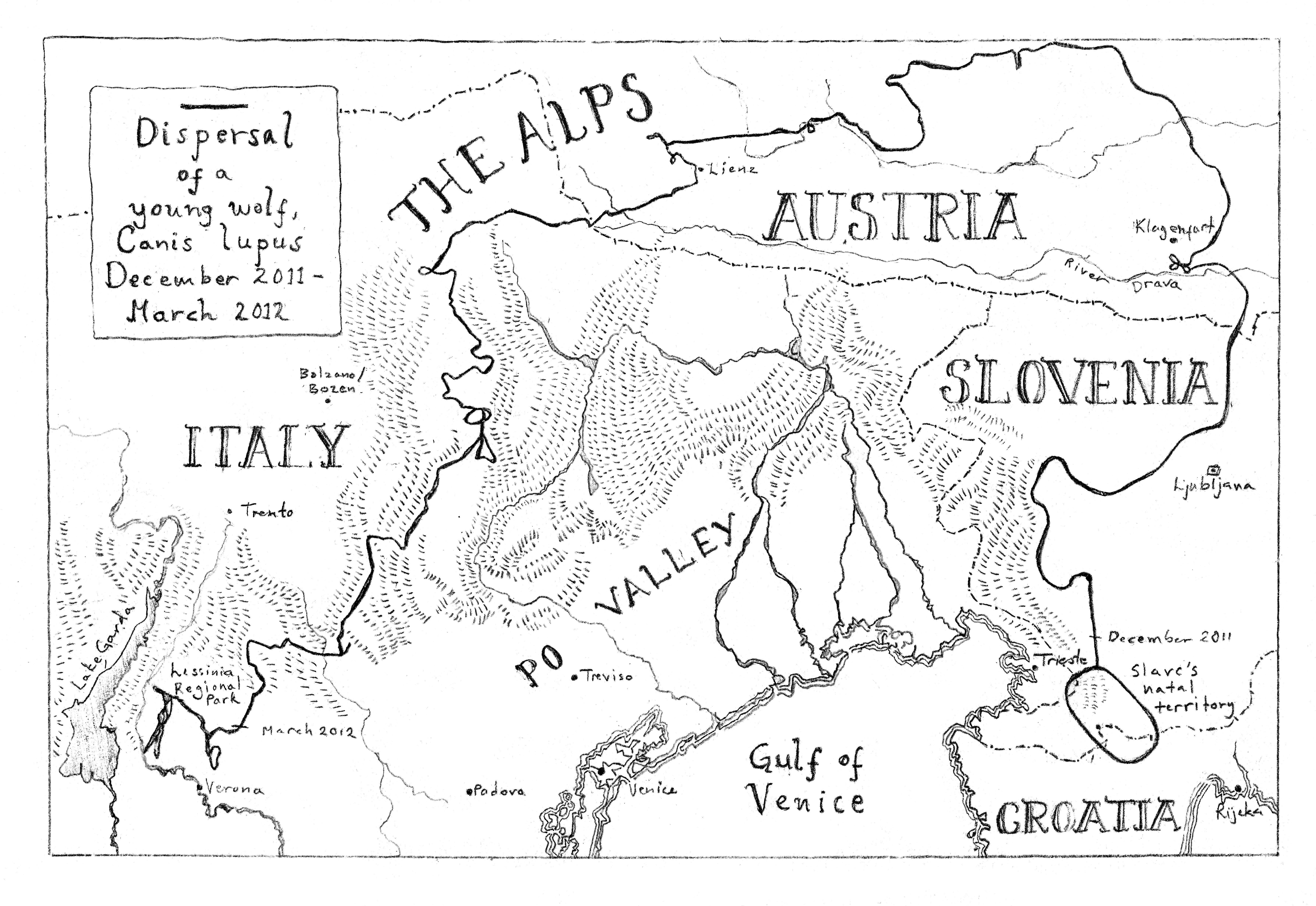

For my book Lone Wolf, I followed one of the pioneers. Slavc was a wolf born in the south of Slovenia in 2010, but at 18 months old, he left his pack behind and set off on a 1,000-mile journey across the Alps. He crossed Slovenia and Austria, and four months later came to Italy, to the foothills north of Verona, where he bumped into a female wolf on a walkabout of her own. Astonishingly, perhaps the only two wild wolves for several thousand square miles had somehow found each other. When they bred, they became the first wolf pack back in these mountains for more than a century. Today, there are at least 17 packs in the region.

Before setting out, Slavc had been fitted with a GPS collar. It gave researchers a unique chance to observe the path of a large carnivore through the heart of Europe; and it gave me an idea. More than a decade later, I embarked, on foot, on the same path Slavc had travelled. I wanted to see how those living alongside the wolf once more were coping with its presence. I found shepherds and farmers working with dogs and electric fences, showing that coexistence with carnivores is possible. But I also found that wherever the wolf has returned, the fear and hatred have come back, too.

Alpine farmers live hard lives in hard places. Climate change, the rocketing costs of energy and feed, young people leaving for the cities; now they are being asked to tolerate the wolf. I could understand their anger. The wolf has become a convenient scapegoat for a range of complex problems, and one that can be addressed with a shotgun. Wolves kill at least 65,500 livestock annually in the EU (by comparison, dogs off the leash in the UK kill an estimated 15,000 sheep a year). Yet those herders taking measures to protect their flocks are often treated as traitors by their neighbours.

Far-right, anti-EU parties, such as Austria’s FPO, have been enflaming tensions in the countryside, refusing to countenance any solution except shooting them. The framing is that wolves are supported by an urban elite with no idea of how the land works. It has been a successful strategy. A 2022 German study found that wolf attacks led to far-right gains of between one and two percentage points in subsequent municipal elections. Only 2 per cent of European voters work in farming, but their voice is loud and they symbolise a much wider discontent about the green transition. It is a discontent that the far right is all too happy to encourage.

Two years ago, when I walked Slavc’s path, a change in law still seemed fanciful. That it has happened so quickly is indicative of how politics is shifting, and how politicised the wolf remains. Countries including Spain, Germany and France have already indicated or enacted changes in law, and other countries will follow suit. “If we could count on logic and rationality and scientific rigour, this decision is not dangerous,” said Luigi Boitani, Italy’s pre-eminent wolf expert. But as I saw in a long walk across Europe, that is rarely how we reason.

Despite their numbers, wolves remain in “unfavourable or inadequate conservation status” in all but one of Europe’s biogeographical regions. A Swedish decision to reduce the country’s wolf population from 300 to 170 risks pushing them into an “extinction vortex”. A coalition of environmental groups is taking the European Commission to court over the decision, in a move backed by hundreds of conservationists. In the meantime, this summer is set to be the bloodiest for wolves for half a century. Whether it harms their numbers, and whether it assuages the anger in the countryside, remains to be seen.

Adam Weymouth’s ‘Lone Wolf’ (Penguin) is out now