Name: Vlad Drăculea, Prince of Wallachia

Dates: 1431 to 1476

Accused of: Impaling up to 100,000 people

Claim to Fame: Bram Stoker's Dracula based loosely on his life

Legends of vampires go back centuries, but few names have cast more terror into the human heart than Dracula. However, the fictional character, created by author Bram Stoker, was inspired by a real historical figure called Vlad the Impaler.

Vlad the Impaler — also known as Vlad III, Prince of Wallachia — was a 15th-century warlord in what today is Romania, in southeastern Europe. Stoker used elements of Vlad's real story for the title character of his 1897 novel "Dracula." The book has since inspired countless horror movies, television shows and other bloodcurdling tales. However, according to historians and literary scholars, the two Draculas don't really have much in common.

Everything to know about Vlad the Impaler

Who was the real Dracula?

Vlad the Impaler is believed to have been born in 1431 in what is now Transylvania, the central region of modern-day Romania. However, the link between Vlad the Impaler and Transylvania is a matter of debate, according to Florin Curta, a professor of medieval history and archaeology at the University of Florida.

"Dracula is linked to Transylvania, but the real, historic Dracula — Vlad III — never owned anything in Transylvania," Curta told Live Science. Bran Castle, a modern-day tourist attraction in Transylvania that is often referred to as Dracula's castle, was never the residence of the Wallachian prince, he added.

"Because the castle is in the mountains in this foggy area and it looks spooky, it's what one would expect of Dracula's castle," Curta said. "But he [Vlad III] never lived there. He never even stepped foot there."

Vlad III's father, Vlad II, did own a residence in Sighişoara, Transylvania, but it is not certain that Vlad III was born there, according to Curta. He said it's also possible that Vlad the Impaler was born in Târgovişte, which was at that time the royal seat of the principality of Wallachia, where his father was a "voivode," or ruler.

However, it is possible for tourists to visit one castle where Vlad III certainly spent time. At about age 12, Vlad III and his brother were imprisoned in Turkey. In 2014, archaeologists found the likely location of the dungeon, located in Tokat Castle in northern Turkey, Smithsonian magazine reported. The eerie place contains secret tunnels and dungeons; it is currently under restoration and open to the public.

Where does the name Dracula come from?

In 1431, King Sigismund of Hungary — who would later become the Holy Roman Emperor, according to the British Museum — inducted the elder Vlad into a knightly order, the Order of the Dragon. This designation earned Vlad II a new surname: Dracul. The name came from the old Romanian word for dragon, "drac."

His son, Vlad III, would later be known as the "son of Dracul" or, in old Romanian, Drăculea, hence Dracula, medieval historian Constantin Rezachevici wrote in a 1999 study. In modern Romanian, the word "drac" refers to the Devil, Curta said.

According to Rezachevici, the Order of the Dragon was devoted to a singular task: the defeat of the Ottoman Empire. Situated between Christian Europe and the Muslim lands of the Ottoman Empire, Vlad II's (and later Vlad III's) home principality of Wallachia was frequently the scene of bloody battles as Ottoman forces pushed westward into Europe and Christian forces repulsed the invaders.

Bram Stoker read a book about Wallachia in 1890, English professor Elizabeth Miller wrote in "Dracula: Sense and Nonsense" (Desert Island Books, 2020). Although the book did not mention Vlad III, Stoker was struck by the word "Dracula." He wrote in his notes that "Dracula in Wallachian language means DEVIL." Stoker likely chose to name his character Dracula for the word's devilish association.

The theory that Vlad III and Dracula were the same person was developed and popularized by historians Radu Florescu and Raymond T. McNally in their book "In Search of Dracula" (New York Graphic Society, 1972). Though far from accepted by all historians, the thesis took hold of the public imagination, according to The New York Times.

Years of captivity

When Vlad II was called to a diplomatic meeting with Ottoman Sultan Murad II in 1442, he brought his young sons Vlad III and Radu along. But the meeting was actually a trap: All three were arrested and held hostage. The elder Vlad was released under the condition that he leave his sons behind.

"The sultan held Vlad and his brother as hostages to ensure that their father, Vlad II, behaved himself in the ongoing war between Turkey and Hungary," Miller told Live Science.

Under the Ottomans, Vlad and his younger brother were tutored in science, philosophy and the arts. According to Florescu and McNally, Vlad also became a skilled horseman and warrior.

"They were treated reasonably well by the current standards of the time," Miller said. "Still, [captivity] irked Vlad, whereas his brother sort of acquiesced and went over to the Turkish side. But Vlad held enmity, and I think it was one of his motivating factors for fighting the Turks: to get even with them for having held him captive."

Vlad the prince

While Vlad and Radu were in Ottoman hands, Vlad's father was fighting to keep his place as voivode of Wallachia, a fight he would eventually lose. In 1447, Vlad II was ousted as ruler of Wallachia by local noblemen called boyars and was killed in the swamps near Bălteni, halfway between Târgovişte and Bucharest in present-day Romania, according to a 2009 study by author John Akeroyd. Vlad's older half brother Mircea was killed alongside his father.

Not long after these harrowing events, in 1448, Vlad III embarked on a campaign to regain his father's seat from the new ruler, Vladislav II. His first attempt at the throne relied on the military support of the Ottoman governors of the cities along the Danube River in northern Bulgaria, according to Curta. Vlad also took advantage of Vladislav's absence at the time, as he'd gone to the Balkans to fight the Ottomans for the Hungarian governor, John Hunyadi.

Vlad won back his father's seat, but his time as ruler of Wallachia was short-lived. He was deposed after only two months, when Vladislav II returned and took back the throne of Wallachia with the assistance of Hunyadi, according to Curta.

Little is known about Vlad III's whereabouts between 1448 and 1456. But it is known that he switched sides in the Ottoman-Hungarian conflict, giving up his ties with the Ottoman governors of the Danube cities and obtaining military support from King Ladislaus V of Hungary, who happened to dislike Vlad's rival, Vladislav II of Wallachia, according to Curta. Meanwhile, Vladislav II sought aid from Ottoman ruler Mehmed II.

Vlad III's political and military tack truly came to the forefront amid the fall of Constantinople in 1453, when the Ottomans were in a position to invade all of Europe. In July 1456, as the Ottomans and Hunyadi's forces were locked in battle, Vlad led a small force of exiled boyars, Hungarians and Romanian mercenaries against his old enemy Vladislav II at Târgoviște, McNally and Florescu wrote in "Dracula, Prince of Many Faces" (Little, Brown and Co., 1989). "He had the satisfaction of killing his mortal enemy and his father's assassin in hand-to-hand combat," they wrote.

Vlad, who had already solidified his anti-Ottoman position, was proclaimed voivode of Wallachia in 1456, Miller wrote in "A Dracula Handbook" (Xlibris, 2005). One of his first orders of business in his new role was to stop paying an annual tribute to the Ottoman sultan — a measure that had formerly ensured peace between Wallachia and the Ottomans.

Why is Vlad called "The Impaler"?

To consolidate his power as voivode, Vlad needed to quell the incessant conflicts that had historically taken place between Wallachia's boyars. Stories from the time immediately following Vlad's imprisonment in Hungary describe his cruelty in torturing the opposition, including cooking people alive, skinning them, and cutting off their limbs and genitals, according to a 2021 study by Aleksandra Bartosiewicz.

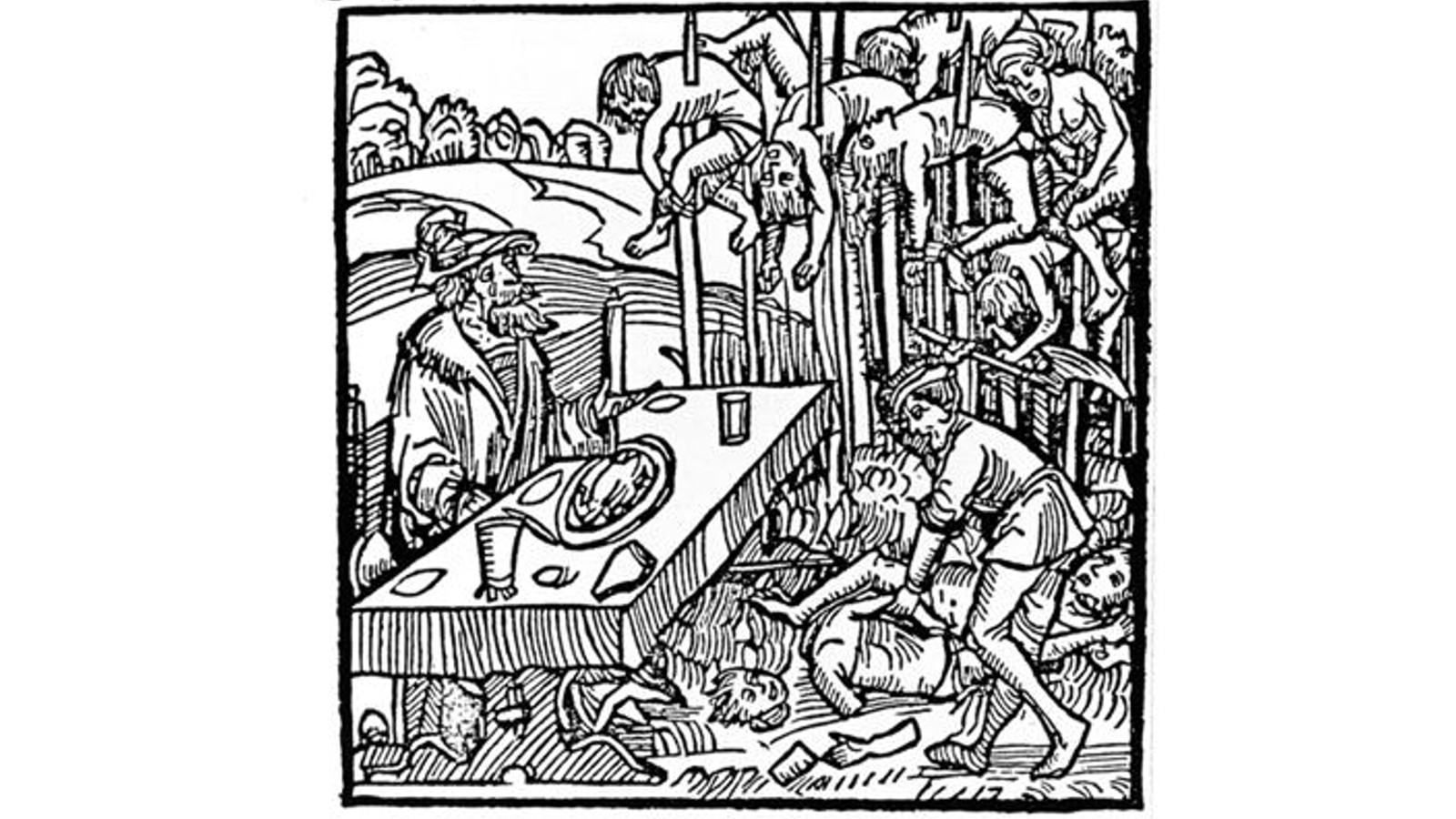

But Vlad's favorite method of public execution of men, women and children was impaling, which involved hoisting a victim on a tall stake. The stake gradually tore their insides over the span of several days before they died of their injuries. Bartosiewicz wrote that estimates range from 40,000 to 100,000 people killed this way by Vlad Țepeș — Vlad the Impaler — as he came to be known in Romanian.

"In the 1460s and 1470s, just after the invention of the printing press, a lot of these stories about Vlad were circulating orally, and then they were put together by different individuals in pamphlets and printed," Miller said. Many of those printing the pamphlets were hostile to Vlad III.

But some of the pamphlets from that time tell nearly the same gruesome stories about Vlad, including a series of legends collected and published in the 1490 story "The Tale of Dracula the Voivode," authored by a monk named Efrosin, who presented Vlad III as a fierce-but-just ruler.

Although a massive number of impalements is often cited in Dracula literature, historian Dénes Harai wrote in a 2025 study that the count is greatly exaggerated due to the sensationalism of the 15th-century reports. Impalement was actually an "exceptional tool for exceptional situations," Harai wrote, and "only a handful of historical records allow us to evaluate the actual number of impalements."

In 1459, for example, Vlad arrested a group of merchants and ordered their impalement. But while one German chronicle claimed the number was 600, another mentioned 41 merchants put to death. Also in 1459, Vlad lured a number of boyars to a banquet to kill them. Although a German chronicle suggested there were some 500 boyars, the place of execution could hold only 40 to 50 impaled bodies, according to Harai.

Based on a thorough survey of the surviving records, Harai has estimated that the real number of impalements Vlad Dracul had carried out was roughly 8% of the total claimed. "These figures certainly do not downplay the brutality of Vlad's rule, but, contrary to the popular legend and the sensationalist claims of some contemporary chroniclers, impalement was not a principal tool for mass killing," Harai wrote.

Vlad's battles

"After Mehmed II — the one who conquered Constantinople — invaded Wallachia in 1462, he actually was able to go all the way to Wallachia's capital city of Târgoviște but found it deserted," Curta said. "And in front of the capital he found the bodies of the Ottoman prisoners of war that Vlad had taken — all impaled."

In one battle on June 17, 1462, known as the Night Attack at Târgoviște, Vlad III and Mehmed II's forces fought from three hours after sunset until about four in the morning at the foothills of the Carpathian Mountains, according to McNally and Florescu. The attack was an attempt to assassinate Mehmed II. Using only torches and flares, the Wallachian forces were unable to locate his tent, and the alarm was raised. McNally and Florescu estimated that 5,000 of Vlad's men were lost, compared with 15,000 Ottomans, but they pointed out that it was "an act of extraordinary temerity, which is celebrated in Romanian literature and popular folklore."

Vlad's victories over the invading Ottomans were celebrated throughout Wallachia, Transylvania and the rest of Europe; even Pope Pius II was impressed.

"The reason he's a positive character in Romania is because he is reputed to have been a just, though a very harsh, ruler," Curta said.

How did Vlad the Impaler die?

Not long after the impalement of Ottoman prisoners of war, in August 1462, Vlad was forced into exile in Hungary, unable to defeat his much more powerful adversary, Mehmed II. Vlad was imprisoned for a number of years during his exile, though during that time, he married and had two children.

Vlad's younger brother Radu, who had sided with the Ottomans during the ongoing military campaigns, took over governance of Wallachia after his brother's imprisonment. But after Radu's death in 1475, local boyars, as well as the rulers of several nearby principalities, favored Vlad's return to power, John M. Shea wrote in "Vlad the Impaler: Bloodthirsty Medieval Prince" (Gareth Stevens Publishing, 2016).

In 1476, with the support of the voivode of Moldavia, Stephen III the Great (1457-1504), Vlad made one last effort to reclaim his seat as ruler of Wallachia. He successfully stole back the throne, but his triumph was short-lived. Later that year, while marching to yet another battle with the Ottomans, Vlad and a small vanguard of soldiers were ambushed, and Vlad was killed.

But Vlad may have been suffering from health issues just before his death. In a 2023 study, researchers used mass spectrometry to study a letter Vlad penned in 1475. The researchers found biological evidence that Vlad had a respiratory tract infection and that he likely had hemolacria, a condition that makes a person cry blood-tinged tears. Hemolacria can result from simple injuries or infections of the eye, but it can also be caused by systemic diseases such as anemia or nervous system issues.

There is much controversy over the location of Vlad III's tomb, Rezachevici noted in a 2002 study. He is said to be buried in the monastery church in Snagov, on the northern edge of the modern city of Bucharest, in accordance with the traditions of his time. But recently, historians have questioned whether Vlad might actually be buried at the Monastery of Comana, between Bucharest and the Danube, which is close to the presumed location of the battle in which Vlad was killed, according to Curta.

One thing is for certain, however: Unlike Stoker's Count Dracula, Vlad III most definitely did die. Only the harrowing tales of his years as ruler of Wallachia remain to haunt the modern world.

Editor's note: This article was originally published Dec. 15, 2021, and was updated Sept. 30, 2025, to include the latest research on Vlad Dracul.