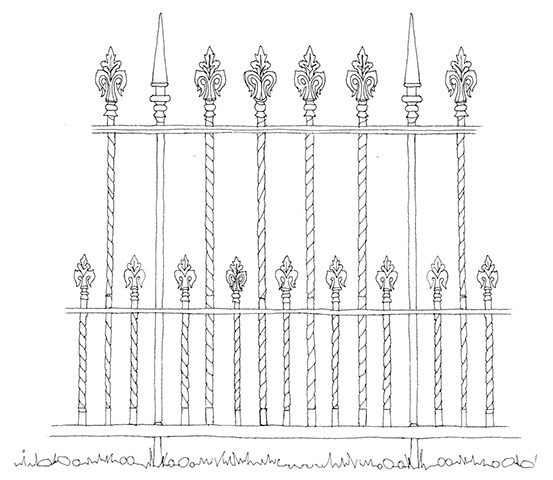

Iron railings became increasingly popular and readily available in the Victorian era and were an impressive introduction for visitors to the quality home. Often decorated with elaborate finials, they might be painted green or brown. After Prince Albert’s death in 1861, many iron railings were painted black as a sign of mourning – and remained so for many decades. During the second world war, many were removed, supposedly for recycling into weapons, though there is now evidence this was largely propaganda to make demoralised citizens feel they were making a contribution to the war effort. Of little value, it seems they were often dumped into the Thames estuary.

Illustration: Emma Kelly

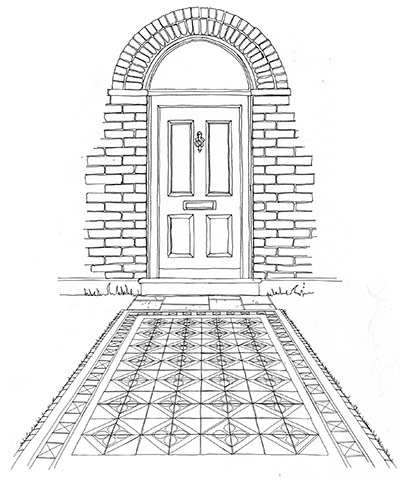

The Arts and Crafts movement, flourishing in Britain between 1880 and 1910, rejected mass production in favour of creativity and individualism; opulent, fussy decoration was ditched for craftsmanship, honest design, traditional building techniques and ordinary materials such as stone and tiles. External features were often built with traditional, local materials and designed to clearly express their structural function.

Illustration: Emma Kelly

As the gothic revival seized Britain from about 1850, even modest-sized domestic buildings tried to imitate the upward swoop of medieval churches. One fairly easy way of creating a spire effect on your house was to decorate the roof with a finial. Finials are architectural devices designed to emphasise the apex of a gable; the more extravagant examples of their kind include floral patterns and sculpted dragons.

Illustration: Emma Kelly

Illustration: Emma Kelly

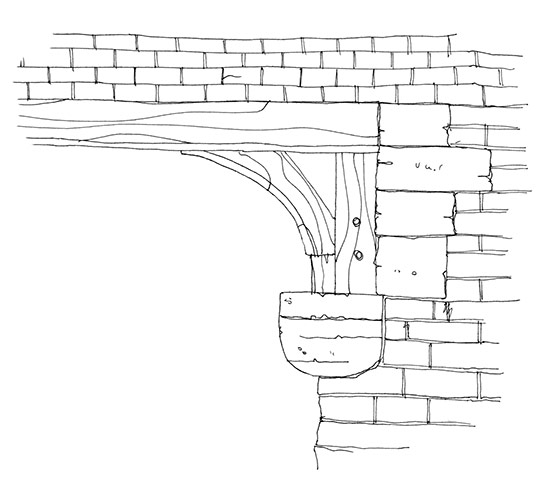

From the 1870s cavity walls became a cost-effective way of insulating and protecting interiors from rain damage and damp. By the late Edwardian period, cavity walls became standard features of new buildings. The walls are composed of two “skins” of masonry, most often brick, separated by a gap of between 50mm and 100mm.

Illustration: Emma Kelly

First employed in the 1670s, the sash window – employing two large panels (or sashes) that slide vertically – came into its own in the Victorian era when a cheaper version of plate glass – sheet glass – was invented in 1838. Thereafter, windows grew wider and glazing bars thinner. Even at this time, only the smarter homes could afford them, and often only on the front facades. By the 1850s, more expensive villas and terraced houses had them, and by the 1870s the style was widespread. The most widely used design, the “six over six” panel window of three panes across by two down for each frame, gave way by the 1870s to the four-paned version with larger sheets. In late Victorian houses, look for ornate cornices or transoms (horizontal bars) on or above the window.

Illustration: Emma Kelly

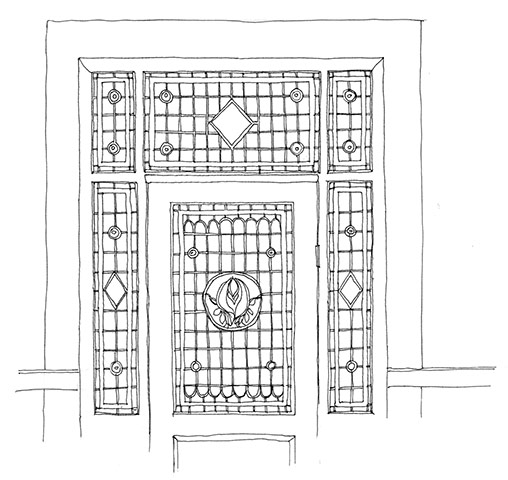

Stained glass enjoyed a renaissance in Victorian times, particularly during the gothic revival, which restored the painstaking mosaic method of leading together pieces of shaped glass. Stained glass with floral and geometric patterns was typically fitted in the upper panels of windows, in entrance panel windows and in front-door panels.

Illustration: Emma Kelly

Before the end of the 18th century, buildings – including roofs – tended to be built of local materials, with land-based transport as yet undeveloped. Then came the canals and, from the 1830s, the railways, and suddenly materials were available nationwide – including slate. Welsh, Cornish and Cumbrian slates for roofs and cladding were shipped around the country and made the material a common feature of Victorian buildings of all kinds.

Illustration: Emma Kelly

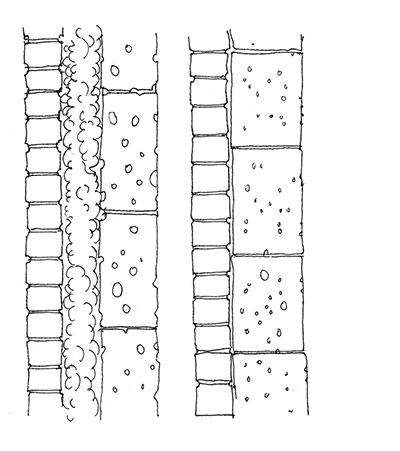

From the mid-18th century onwards, steam power enabled brick manufacturing to become mechanised, and deeper, denser clays became available, as well as washed and graded aggregates. These afforded better strength, regularity and a range of colours. By the end of 19th century, machine-made bricks with sharp edges and a durable surface were being transported all over the country – though their extra cost meant they were often used only for facades. The accuracy of the machine-pressed bricks meant joints could be reduced to just 8mm and brickwork could be laid more easily. The greater variety of bricks manufactured during the Victorian period meant different colours were now more readily available, and the Victorians started patterning their external walls with enthusiasm.

Illustration: Emma Kelly

In the late Victorian and Edwardian eras, bay windows began bulging outwards, usually covering their modesty with a small slate roof. Here’s a handy dating trick: if you spot a bay window on a smaller domestic building, it’s very likely to have been built after 1894, when an amendment to the building act decreed that windows no longer need be flush with the exterior wall. Canted bay windows – those with a straight front and angled sides – became a particularly fashionable and popular feature of middle-class Victorian terraced houses and villas.

Illustration: Emma Kelly