MEXICO CITY — Rosa Maria Trejo got here to the Mexican capital thanks to a brother residing in Arizona who sent money to help finance the difficult trip from their native Venezuela. He now provides cash for food and lodging at a small hotel while she figures out what to do next.

She hasn’t abandoned her plan to get to the United States.

“I don’t want to stay in Mexico, but I also don’t want to go back to Venezuela,” said Trejo, 27. “My brother tells me it’s best to wait here until the situation in the United States changes.”

Tens of thousands of Venezuelans stuck in Mexico appear to be making the same calculation as hope spreads that the United States will soon start letting them in again — two months after federal agents began turning them away at the U.S.-Mexico border without a chance to apply for political asylum.

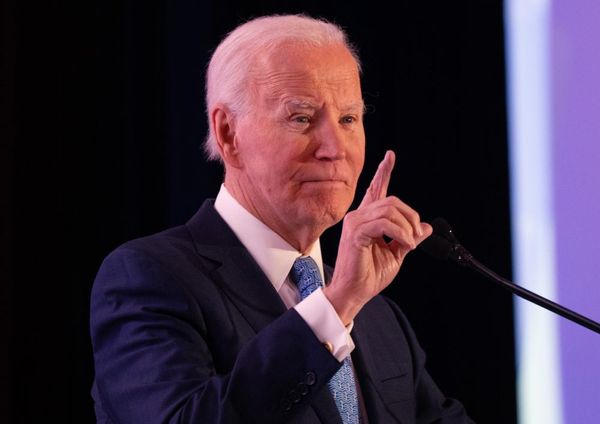

The authority to keep them out came from a decades-old public health law known as Title 42 that was resurrected by the Trump administration during the pandemic. The Biden administration fought the law in court but used it anyway — first only for Mexicans and Central Americans but then for Venezuelans after record numbers converged on the border, political pressure mounted to crack down and Mexico agreed to let them back in.

As a result, Venezuelans are now ubiquitous in shelters, soup kitchens and homeless encampments from the sweltering jungles of Panama to the streets of this traffic-clogged capital to desert towns along the Rio Grande. Some beg for coins and food. Others rely on charity, odd jobs and help from relatives.

Last month, however, a federal judge ruled that that using Title 42 to restrict immigration was “arbitrary and capricious,” giving the Biden administration until Dec. 21 to end the practice.

What border strategy the White House will employ next remains to be seen. Many Venezuelans stuck in Mexico have adopted a wait-and-see approach.

“A lot of people are saying that the Americans are going to give us another chance — but we don’t know anything with clarity,” said Carlos Fernández, 36. “I want to have faith, to believe that we will be able to cross into the United States.”

The Mexico City shelter where he is staying is designed for 90 people but is now home to 500, mostly fellow Venezuelans. A mechanic, Fernández said he hopes to find work in the United States to help his wife and two young children, who remain back in the northeastern state of Sucre.

“What Biden did caught us by surprise,” said Fernández, referring to the mid-October expansion of Title 42 to target Venezuelans. “We were basically left in limbo.”

Mired in economic, political and social upheaval, Venezuela has seen almost 7 million people — about a quarter of the country’s population — leave since 2014. Most have settled in neighboring Colombia and other South American nations.

The exodus slowed as economic conditions improved slightly in Venezuela, and some migrants returned. But the United States, not a major initial destination, became a magnet in the last year or so as word spread among Venezuelans that asylum-seekers arriving at the border were being allowed to enter the country.

“We heard it was like a green light, Biden was letting everyone in,” said José Díaz, 32, who, along with his wife, was among scores of migrants seeking aid outside the Venezuelan Embassy in Mexico City. “But that all changed once we were here.”

The use of Title 42 to send Venezuelans back to Mexico came as soaring numbers were arriving at the southwest border. In fiscal 2022, U.S. officials reported detaining almost 190,000 Venezuelans along the border — triple the previous year’s total.

In September — before the Biden administration invoked Title 42 — U.S. border guards detained a record 33,000 Venezuelans. Most were allowed into the United States to apply for asylum.

Many Venezuelan migrants sell homes or borrow heavily to finance their journeys, which can cost more than $5,000. Most travel overland from South America through the Darién Gap, a strip of dense jungle that joins Colombia and Panama, before making their way through Central America to Mexico.

They tell stories of being robbed in Mexico or detained in crowded lockups where the food is barely edible.

In October, Mexico reported apprehending 52,262 migrants, a record for a single month. Venezuelans represented the largest single group, about 42% of all detainees. Most were eventually released and told to leave the country — a stricture that many ignore, lacking the funds and desire to go home.

Instead, many have hunkered down in Mexico.

Nearly 13,000 Venezuelans applied for political asylum in Mexico in the first 11 months of this year, 39% more than the combined total of the previous two years.

Many applicants for political asylum acknowledge that their aim is to maintain proximity to the United States and keep alive aspirations of moving there.

“Maybe we only have to wait in Mexico a little while until the United States lets us in,” said Christian Ontuño, 45, a Venezuelan who was among those queuing up outside the central refugee office in Mexico City.

Some Venezuelans, exhausted and broke, have given up on the American dream and are trying to get home. Several hundred have managed to score free seats on flights from Mexico City to Caracas sponsored by the Venezuelan and Mexican governments.

“I’d rather go back through the jungle than have to travel through Mexico again,” said Rosa Bustamante, 29, who spoke from outside the Venezuelan Embassy in Mexico City on a recent morning as she sought a place on a flight. “In Mexico they throw you in jail. They give you spoiled food. They rob you. They threaten you. They extort you.”

It had taken her two months to travel from her home in the Venezuelan state of Táchira, on the border of Colombia, more than 3,200 miles to Mexicali — where she and several compatriots entered California and surrendered to the Border Patrol.

All were quickly dispatched back to Mexico, said Bustamante, a former firefighter and pharmacy worker who left her 12-year-old son in Venezuela with her parents.

“Everything on this trip has turned out badly,” she said as her eyes welled with tears. “Better I return now to my homeland. Yes, it’s time to go home.”

All around her on the grimy street were fellow Venezuelans sleeping under blankets, shivering in the winter chill, some also seeking to go back — but others determined to continue their epic journeys north.