Few criminal trials in recent history have piqued the public interest like Erin Patterson’s conviction for poisoning three extended family members with a beef wellington spiked with death-cap mushrooms. Two books about the trial have already been announced, the second within 24 hours of her guilty verdict for murder and attempted murder.

Other noted Australian authors, including Helen Garner and Guy Rundle, have been spotted in the courtroom. Chloe Hooper has written about the case for the Saturday Paper. Could there be more books on the way?

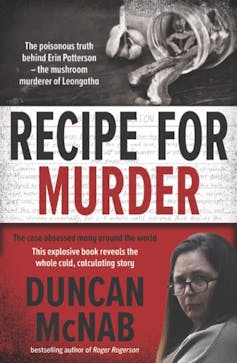

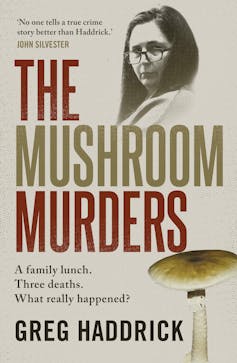

Publisher Hachette issued a press release with a cover for Recipe for Murder by journalist Duncan McNab, and a publication date of October 14. Greg Haddrick’s book, The Mushroom Murders will be published by Allen & Unwin just one month later on November 11.

McNab is a journalist, and a former police detective and private investigator. Haddrick a screenwriter and true crime writer.

According to Hachette, McNab draws on “his extensive investigative experience”, with an in-depth look into the nine-week trial that combines “first-hand access, courtroom experience” and “rigorous research”.

Meanwhile, in the Allen & Unwin press release, Haddrick says,

there are so many details omitted from the media’s daily summaries of the proceedings that make this a much bigger story than people realise.

Both publishers are keen to emphasise the books will have new information – even for those fixated on the media coverage. In book form, there is greater scope for description and more room for detail, which can afford greater nuance and complexity.

McNabb and Haddrick would be accustomed to pumping out pages faster than your average literary fiction author. Even so, a few months from the conclusion of the trial to a copy on shelves is an impressive timeframe for releasing a book.

In a competitive attention economy, big media events like the mushroom trial have already grabbed nationwide (even global) interest – and offer the possibility of accessing those bigger audiences. How does a publisher race a book to shelves – and what are the risks along the route?

Making a book – fast

The media saturation of the case has generated multiple podcasts. Now, documentaries and an ABC TV series are in the works. How does a famously slow-moving industry get a book onto shelves at a fraction of the usual schedule?

Ordinarily, publishing production schedules run to the months and years – even after an editor has received a full manuscript. The editorial process usually involves a structural edit, which looks at the big picture (things such as tone, setting and plotting), then copyediting, which is more fine-grained and should involve fact-checking.

Then, the manuscript is typeset and proofread. Printing will take around three weeks to a month. The finished books sit in the warehouse for a month before publication date, as the distributor gradually ships them out to stores.

For topical books like these, the schedule looks very different. A manuscript may be delivered in sections and edited in segments. Steps such as legalling – having an external lawyer check the work for defamation and other risks – still take time, though, and explain part of the reason why the books will not be available immediately.

Grabbing attention where it is

Reading rates are declining – in Australia and elsewhere – thanks to escalating competition from other forms of media, from podcasts and streaming to social media. With so many demands on our attention, deciding to consume a book instead of a podcast or social media post means a much greater time commitment.

Publishers are keen to tap into content that will appeal to as broad a readership as possible. The regular audience of the more successful podcasts is around 200,000. By comparison, for a book to sell 200,000 copies, it would generally be one of the top three titles for the year.

Potential for errors

Tighter timeframes can bring greater potential for errors, though. The finished book might involve material seen as defamatory, sparking a lawsuit. Events could be overtaken by an appeal – and (possibly) even an overturned conviction.

While legal expert Rick Sarre has judged the case “virtually appeal-proof”, it has been reported that Patterson will appeal her conviction. If it were successfully appealed, that would be grounds for recalling and pulping the title.

If a title must be recalled, the publisher needs to get the copies back from the booksellers and dispose of them. Dealing with a recall for a commercial book could easily run into the hundreds of thousands of dollars.

However, simply having more time in the production schedule does not make books bulletproof. Federal Court documents showed a senior editor of Belle Gibson’s cookbook The Whole Pantry, in which Gibson claimed her diet had cured her of cancer, had expressed “concerns” about the book’s content. It also identified “gaps” a journalist might probe. But this didn’t result in a fact check. After Gibson’s fabrications were exposed, The Whole Pantry was pulled from shelves.

Courtroom classics not made by speed

Some of the most successful courtroom coverage in literature has not been based on speed.

John Bryson’s 1985 book Evil Angels, on Lindy and Michael Chamberlain’s trial for the murder of her baby daughter Azaria, is an enduring Australian classic, as a book and film. It was published following the Chamberlains’ 1982 trial and after their High Court appeal against their guilty verdict was lost in 1984. Later versions of the book include the Chamberlains’ 1988 exoneration.

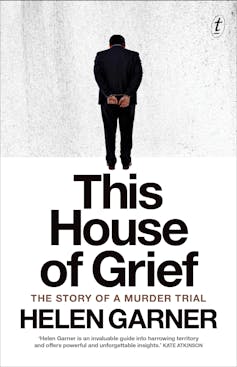

Helen Garner’s courtroom reportage bestsellers, such as This House of Grief about divorced father Robert Farquharson’s trials for drowning his three sons on Father’s Day, come to mind. He was convicted by juries in 2007 and 2010; Garner attended both trials. Her book was published in August 2014 – she famously took her time to write it in the considered way it deserved. What made it so compelling was not how quickly it came to market, but its analysis of the human condition.

Alice Grundy has received funding from the Australia Council for the Arts. She is Managing Editor of Australia Institute Press.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.