Allegedly, American television did exist before Twin Peaks. But there is an undeniable chop down the middle of it, with the likes of Lucy Ricardo, JR Ewing and Captain Kirk on one side, and on the other the body of Laura Palmer – the most beautiful phantom in the world, murdered, wrapped in plastic and burning with secrets. Nothing was quite the same after she washed up on the side of that riverbank in April of 1990. Twin Peaks co-creators David Lynch and Mark Frost destabilised the entire television landscape with a series that was a murder mystery, a soap, a comic pastiche of the American heartland and your worst, weirdest nightmare all at once.

“There were only three networks back then,” says Frost today. “TV was designed to sell you products in the commercial breaks, then lull you into a state of sleep.” But a murdered girl, he and Lynch thought: “What if she was a trojan horse? And what if once we were indoors, inside our little horse, we could wait until everybody fell asleep and climb out and get to work?”

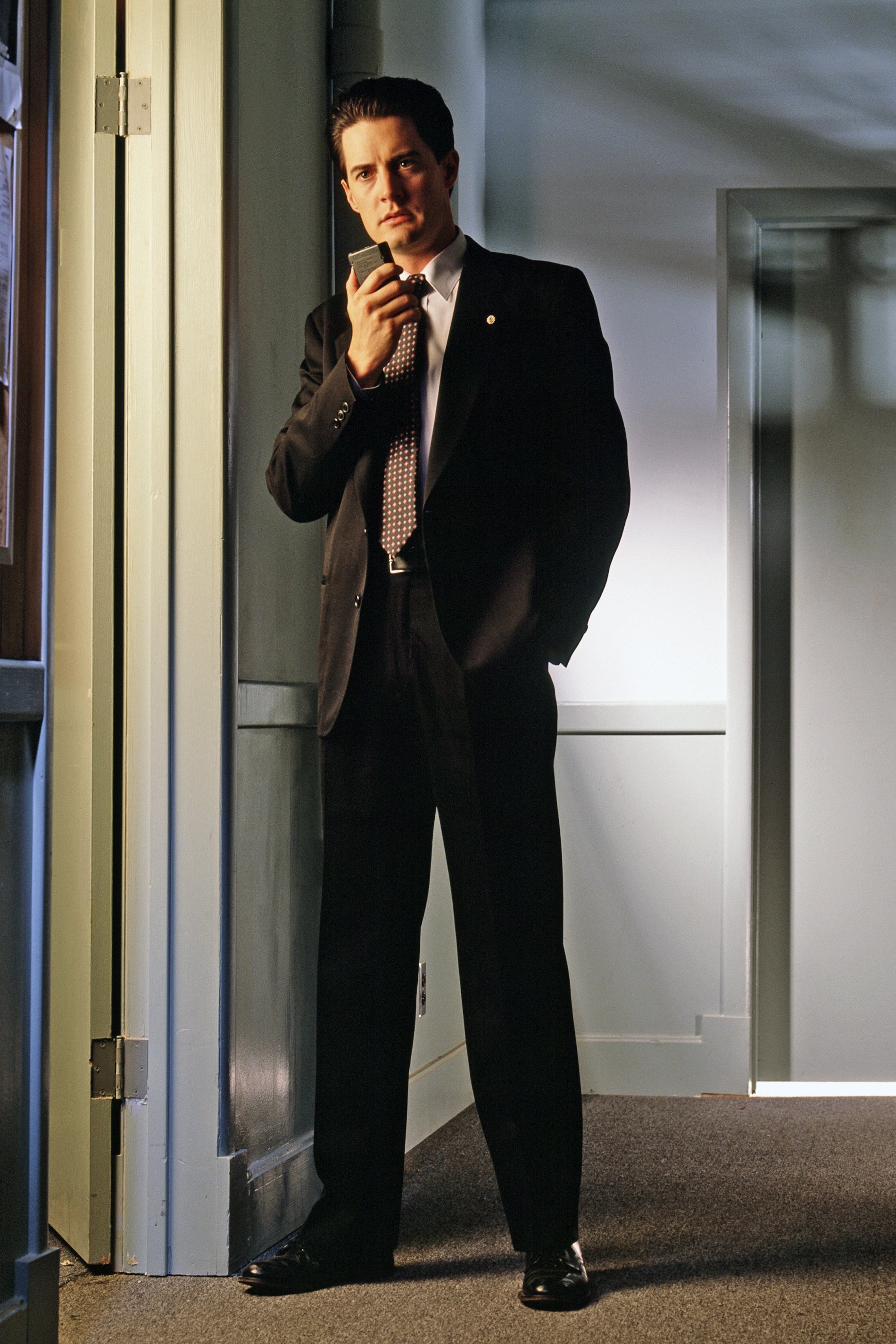

That work has never lost its beguiling power. The story of a small community rocked by a grisly crime – which is then investigated by Kyle MacLachlan’s winsome FBI agent Dale Cooper – Twin Peaks unveiled its true agenda week by week. By its second season, it had become a series that leapt between dimensions, depicted horrifying scenes of murder, and spoke to the macabre darkness often lying beneath modern life. And it was a phenomenon, a rare moment of ambitious, boundary-breaking art and mainstream entertainment as comfortable bedfellows. Today, the fact that something as resolutely non-commercial as Twin Peaks was so huge is possibly one of the most surreal things about it.

It’s now been 35 years since the show’s original broadcast, and this week Twin Peaks and its mesmerising follow-up seriesThe Return, released in 2017, both become available to stream on Mubi. Frost, speaking from his beachfront home in California, suggests newcomers should approach the series “cautiously”. “It has proven to be pretty habit-forming,” he jokes.

The show’s streaming release is also bittersweet, arriving five months after Lynch’s death from complications of emphysema. That he died at all remains slightly jarring: this was a man who spent much of his creative life (from his suburban nightmare tale Blue Velvet and his Hollywood psychodrama Mulholland Drive to his gentle, cross-country experiment The Straight Story) subsumed by thoughts on the great beyond, how we fear it or welcome it, asking what’s there and what’s not there, and who. What a strange, beautiful thing that he now knows all the answers.

“We spoke about death often,” Frost says. “It becomes a spiritual conversation. What are we here for? Who are we? What does being alive mean? What does it all add up to? You ask more of those questions as you get older and the answers don’t come any easier – but the questions get more pressing.”

As David put it, ‘“Twin Peaks” people are party people.’ They want to get together and watch the show and go to work and talk about it the next day

Frost and Lynch were brought together in the mid-Eighties by their agents, who thought the pair would make strong creative partners. Frost was a writer for the influential cop show Hill Street Blues, while Lynch was fresh from Blue Velvet. Their shared success gave them unusual power within the halls of TV network ABC, something likely facilitated by the channel’s commercial struggles at the time. “We had creative rights enshrined in our contracts, but there was still a dance I had to do with the network on an episode-by-episode basis,” he remembers. “Lawyers for ABC were always on at us, covering their asses basically. You couldn’t possibly upset or offend anybody – but we wanted to upset people. And we didn’t mind offending people either.”

While the most graphic sex and nudity – as well as more overt drug use – was saved for the 1992 film prequel Fire Walk with Me, scenes of violence in the series remain deeply disturbing. One moment in the show’s second season, in which a character is pursued around her living room by the embodiment of all evil, is likely enshrined in the memories of anyone who has ever seen Twin Peaks.

And it’s this, Frost thinks, that did the original series in. The first Twin Peaks only ran for a relatively short period of time (30 episodes between 1990 and 1991), ultimately falling foul of the conventions of the era’s broadcast television. “ABC was owned by a [media company] called Capital Cities, who were very conservative – politically, financially, socially,” he says. “I remember meeting the president of that group at one point, and I felt like he was afraid he was going to catch something from me when I shook his hand. They were truly, deep down, kind of horrified by the show because it broke all the rules. They benefited from it, and raked in the dough and got [viewing figures] from it that they hadn’t seen in years, but they were also trying to cram it into a box so that they could feel better about it. And David and I just didn’t want to play that game.”

Despite the Laura Palmer whodunnit making the show instant watercooler television, ABC insisted that Lynch and Frost reveal her killer as soon as possible, and threatened to pull the plug on a second season unless they acquiesced. The build-up to the revelation is propulsive and devastating, capped by an extraordinary confrontation between Cooper and Laura’s killer – but then Twin Peaks famously falls off a cliff, running for 13 more episodes in which most of the show’s cast find themselves trapped in bizarre, unsatisfying subplots. “We were faced with the problem of, ‘OK… what do we do with our second act?’” Frost says. “You see the show is trying to catch its breath and the tone wobbles a little bit. Some people felt it got a little silly.”

He lays the blame, however, firmly at ABC’s feet – theorising that their decision to move the show from Thursday to Saturday nights (traditionally the least-watched night on American television) was deliberate. “Saturday nights are a graveyard on US TV,” Frost says. “It’s for shut-ins and the elderly, basically. As David memorably put it, ‘Twin Peaks people are party people.’ They want to get together and watch the show and go to work and talk about it the next day. Thursday was the perfect night for it. So ABC started killing the golden goose before we ever got to the chopping block.”

In the immediate aftermath, Lynch and Frost went their separate ways, burnt out by an increasingly difficult experience. Lynch remained in the Twin Peaks world via Fire Walk with Me, an absurdly gorgeous yet harrowing prequel film exploring the last days of Laura’s life. It was a financial and critical bomb in 1992, but is now widely regarded as a cult classic. Frost, meanwhile, wrote novels. Years later, on the heels of a successful Twin Peaks DVD release and continued interest in the story, the pair reunited and began plotting a follow-up series.

The Return was broadcast not on ABC but the premium cable channel Showtime (a change that itself reflected how television had evolved in the interim), and allowed Lynch and Frost’s creativity to be entirely untethered. Freed from the shackles of a murder mystery plot, the 18-episode series leant further into absurdity and horror, and abandoned traditional narrative for a kind of wavelength or mood. Laura’s murder is a totem around which the show’s dizzying plot strands orbit, but even that feels a bit cut-and-dry as a description. The show was jazz, basically. Grisly, devastating jazz. “It is absurdly different from the first two seasons,” Frost says, “but in ways that I think reflect who we’d become as people in those 25 years, and what time had done to all of us.”

Contrary to rumour, there were no plans for more Twin Peaks at the time of Lynch’s death, with the pair feeling as if The Return was an ending while they were writing it. Frost, though, misses him. “We enjoyed each other’s minds,” he says. “It was like playing tennis with somebody who was the perfect match for you as an opponent. We challenged each other to do our best work, and that was true all the way up to the end. It was magical.”

‘Twin Peaks’ and ‘Twin Peaks: The Return’ stream on Mubi from 13 June. The original ‘Twin Peaks’ pilot screens as part of the BFI’s Film on Film Festival on 15 June, with a Q&A with Kyle MacLachlan

OceanGate CEO’s reckless behavior before Titan implosion revealed in new documentary

The end of the world as we know it: why the climate apocalypse genre is still on fire

Who can – or could – ever replace David Attenborough?

The Gold’s Charlotte Spencer: I worry acting is becoming only accessible for the rich

How the insufferable waiting game ruined the way we watch TV

The true story behind A Widow’s Game is even wilder than the Netflix film