I can hardly believe it. Britain’s most prestigious/pretentious/exciting/risible (take your pick) art award is back, more or less in its classic form. After a year when the Turner Prize looked close to putting itself out of business by letting the contestants share the prize (2019), there was a year when it was actually out of business due to Covid (2020). Now after a year of (mostly duff) collectives (2021), we’re back with four artists slogging it out on a level playing field.

This year, indeed, the field is – arguably – more level than most. All four artists are female or non-binary, and three are non-White. In the current environment you’d hardly expect anything else. And great.

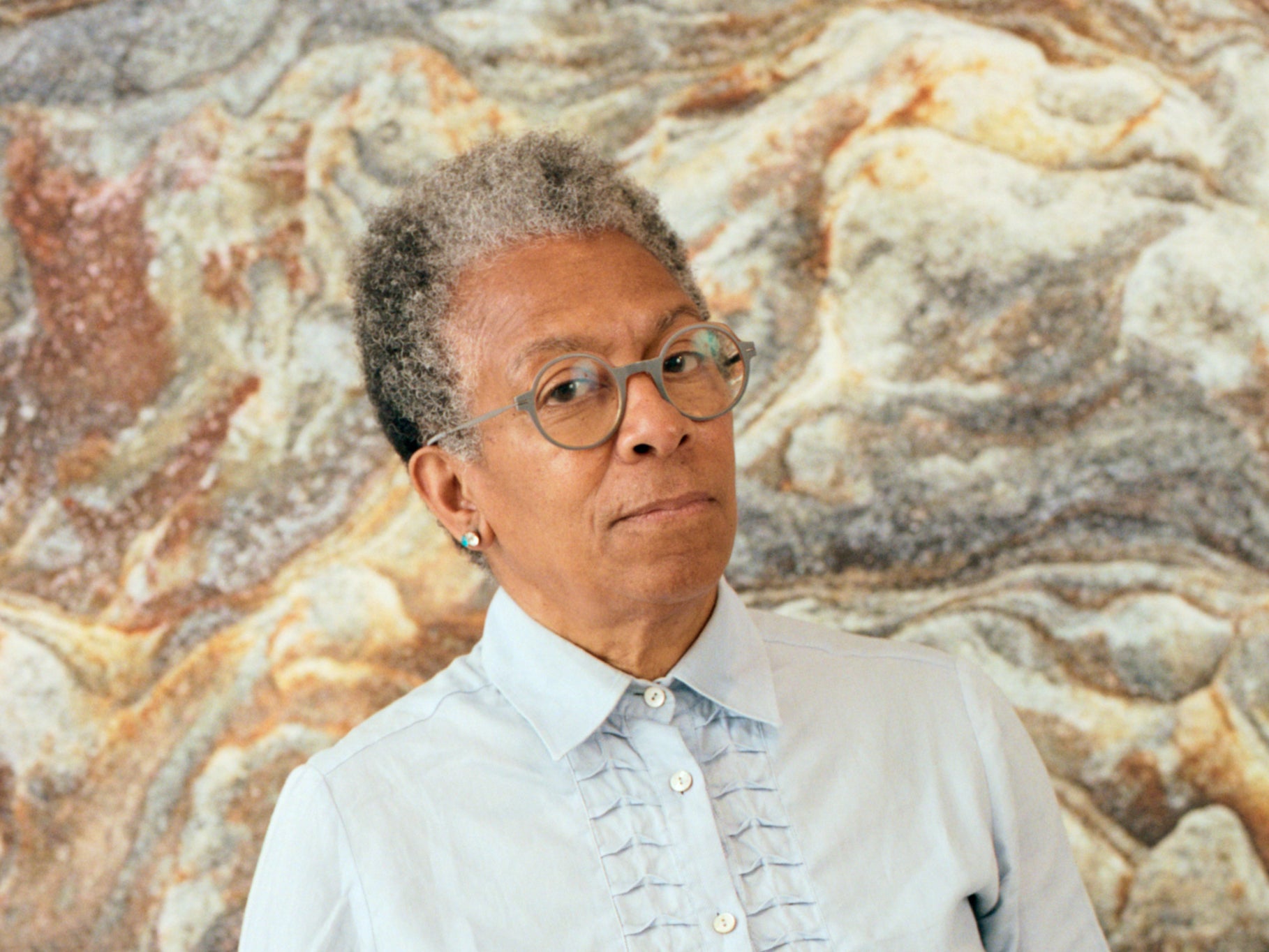

All set, then, for a good tabloid-baiting dust-up in the great Turner Prize tradition? Not quite, as the four seem to fall into two distinct camps. Ingrid Pollard (68) and Veronica Ryan (66) are veteran Black British artists – both of Afro-Caribbean origin – who have only recently received acclaim after decades of dogged art and activism. Heather Philipson (44) and Sin Wei Kin (31) are not only considerably younger, but appear to be here to represent the bracing forefront of art right now.

So will the competition favour experience, with the inevitable implication that it’s making an award for lifetime achievement – which the Turner is specifically designed not to be? Or will it go for the riskier proposition of youth, opting for art that offers in-your-face newness, but which may soon date, while snubbing two highly esteemed senior artists into the bargain?

Heather Phillipson has the advantage of having produced two of the most visible artworks of recent years with her fly-on-an-ice cream sculpture for Trafalgar Square’s Fourth Plinth and her vast psychedelic junk-yard installation RUPTURE NO. 1: blowtorching the giant peach in Tate Britain’s Duveen Hall. Her work here is a scaled-down version of the latter, a “pre-post-historic environment” as she describes it, of eco-themed projections – animals’ eyes, ominous clouds – glowing plastic boulders and disembodied voices, all bathed in acid-tinged pinks and purples. As a hippy-trippy micro-rave it makes an arresting start to the show.

Veronica Ryan’s is the most low-key contribution, looking at the medicinal and spiritual properties of the Caribbean fruit and foodstuffs with which her Montserrat-born mother nurtured her during her London childhood. She replicates seeds and nuts in various materials, suspending them from the ceiling in string bags referencing the crocheted doyleys seen in Caribbean homes. The comforting cushions littered around the installation are cast in plaster.

Drawing out the resonances of objects and recreating them in incongruous materials have become common tropes in recent art. This potentially touching meditation on the transmission of knowledge between generations doesn’t deploy them strongly enough to make the tableau really resonate in the mind. Judging by other work such as her giant bronze-cast tropical fruit in Hackney’s Ridley Road market, Ryan has sold herself somewhat short.

Toronto-born, London-based Sin Wai Kin is the revelation of the exhibition with her super-slick blend of TikTok style self-advertisement, Peking opera and pop video pizzazz. Manipulating their identity with make-up, prosthetics and cutting-edge video trickery, Sin transmutes themselves into all four members of a fantasy boy band. Their preposterous eye-rolling performances offer us the classic Gen Z promise that “It’s Always You” when we know damn well it’s always them – the artist, the boy band – but it’s certainly not “you”. Flawlessly professional in execution, Kin’s work relies on the kind of spine-tingling novelty that is immediately killed by the slightest sense of familiarity. It’s hard to imagine they’ll maintain that sense of exhilarating nowness for long.

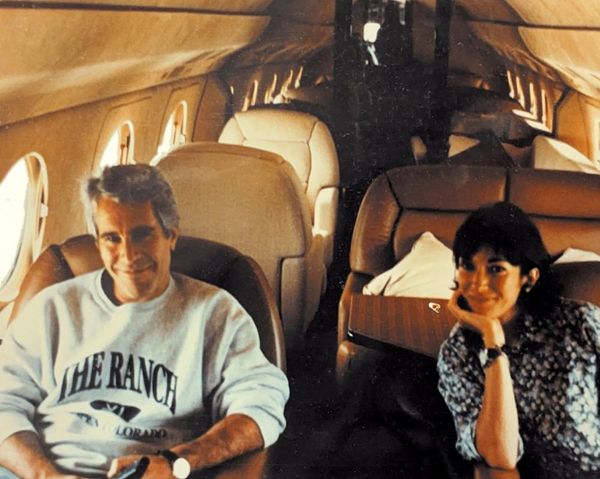

Ingrid Pollard’s photographic investigation into the image of the “Black Boy” in British culture, from appearances on pub signs, cameos in Virginia Woolf novels and street names in faceless suburbia, is cleverly conceived and beautifully executed, but slightly dated in feel. Pollard is extracting the ghostly presence of the Black Boy as demon, slave and mascot from the unregarded byways of British history – the kind of slightly rarefied project artists were undertaking before the seismic upheaval of Black Lives Matter. And, sure enough, the work dates from 2019.

No Cover Up (2021), a collection of banners printed with images of anti-racist and gay rights demos from the Seventies and Eighties feel oddly more current. Intimate photographs with handwritten provocative texts, clearly related to Pollard’s own gay experience – “castrator, bulldagger, dyke” – are the oldest works in the show, dating from 1991, but have a sense of deeply felt, personal experience utterly lacking in everything else in this exhibition. Her best work here is Bow Down and Very Low – 123 from last year, in which three rudimentary robotised figures, cursorily assembled from everyday objects, endlessly perform the same awkward, grinding actions. The central “figure”, formed from a wheelchair and a great loop of rope, makes a lurching, bowing movement, while attendant figures, one just a piece of bent piping, the other formed from two squealing saws, swing at it with a baseball bat and a stick.

A photograph behind shows a vintage photo of a young Black girl bowing. Whether she’s doing it through pride or deference – as the wall text wonders – she seems condemned to repeat the action, just as the oppressive forces bearing down on her lash out with their stunted, Pavlovian gestures. As a metaphor for the condition of Black Britain, these creaky surreal figures have an undeniable grim humour.

This is far from the worst of Turner Prize exibitions, but certainly not among the greatest. While the award feels more or less back on track, there’s no obvious winner. It’s surely the function of an award like this to break new ground, but I wasn’t entirely persuaded by either Phillipson or Sin. Phillipson’s environment-meets-happening gives a superficial impression of taking us somewhere magical and strange. But once you’ve taken in the fact it’s all about climate change, it starts to feel a bit obvious and illustrative. Sin impresses with sheer confidence and cleverness, but her apparent send-up of Gen Z me-me-me waffle feels, at times, like just more me-me-me waffle. So, because artists don’t have to be young to break new ground, and we need to cherish art that has evolved through hard-won wisdom, I’m backing Ingrid Pollard for the Turner Prize 2022.

From 20 Oct until 19 March