In early 1976, Canadian photographer Greg Girard flew from Los Angeles to Tokyo. He had a multistop ticket and a vague plan to visit a number of yet-to-be-determined Asian destinations.

Landing at Tokyo’s Haneda airport, he took a commuter train into the Japanese capital for what he expected would be no more than a quick look around. Walking the city streets from night to morning, he experienced an instant attraction to the city, and an intense curiosity about its mix of non-Western customs and hyper-modern urban surfaces.

“It was just so obvious that it was a kind of science-fiction place – that word just popped into my head looking out the train window at the city. I thought, ‘Why didn’t anybody tell me about this?’ It was clear that first night that I wanted to stay.”

Few would have described the Tokyo that Girard discovered in 1976 as one of the great destinations of the world. Foreign visitors were more likely to complain that Tokyo was a planless maze: chaotic, featureless, polluted, a city concerned only with economic growth.

Girard’s sense that Tokyo was somehow the gateway to the future was intuitively on the mark, however. His arrival came at a time when Japan was on the cusp of an unexpected metamorphosis.

After the Opec “oil shock” of 1973 had suddenly rendered the country’s prosperous industrial sector financially vulnerable, Japan’s leaders gambled and threw government support to the country’s emerging hi-tech companies – the makers of integrated circuits, semiconductors and consumer electronics products. That bold move paid off handsomely.

Thanks to the rapid global ascent of Sony, Toshiba, Sanyo and Panasonic, Japan’s post-war “economic miracle” would roll on for another decade, and Tokyo would be adroitly rebranded as the cool, futuristic hub of a new electronics-based consumer culture.

Having decided to attempt a prolonged stay in Japan, Girard found that things fell into place with surprising ease. At the youth hostel where he initially roomed, he met a young American man who explained how to make a living in Tokyo by giving English lessons – and then handed over his own existing classes to Girard. With the modest income of these classes, Girard was able to rent a tiny apartment of his own.

Girard spent his first months in Tokyo getting to know the city. He was fascinated by the labyrinthine underground passageways, filled with shops and small restaurants, that connected the subway and railway stations – “a whole life underground,” as he recalls it.

He marvelled at the insatiable Japanese hunger for foreign cultural imports, evident in the extensive network of art-house cinemas scattered throughout the city, which offered recent films not only from Japan but from Europe and North America as well.

He was mesmerised by the innovative Japanese graphic design and advertising displays that he saw everywhere around him.

To see photography exhibited in Tokyo in the 1970s meant seeking out the company-sponsored galleries – or “salons”, as they were typically called – of major camera manufacturers such as Nikon and Canon.

Photography magazines such as Asahi Camera and Camera Mainichi, which mixed technical articles with portfolios of work by established and emerging photographers, provided a better window to the current state of photography in Japan.

Girard, who was constantly aware of living on a tight budget, flipped through the pages of these magazines while standing in bookstores. He recalls seeing work by leading Japanese photographers – figures such as Shomei Tomatsu, Daido Moriyama and Eikoh Hosoe – but his chief concern was not other photographers.

“I was more interested in making pictures than in looking at them,” he says.

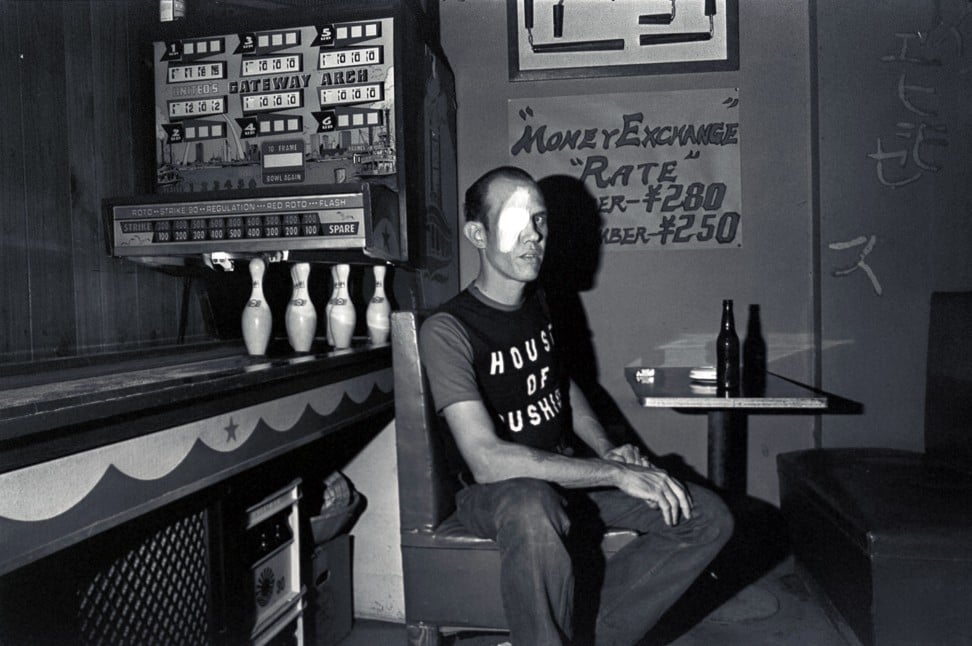

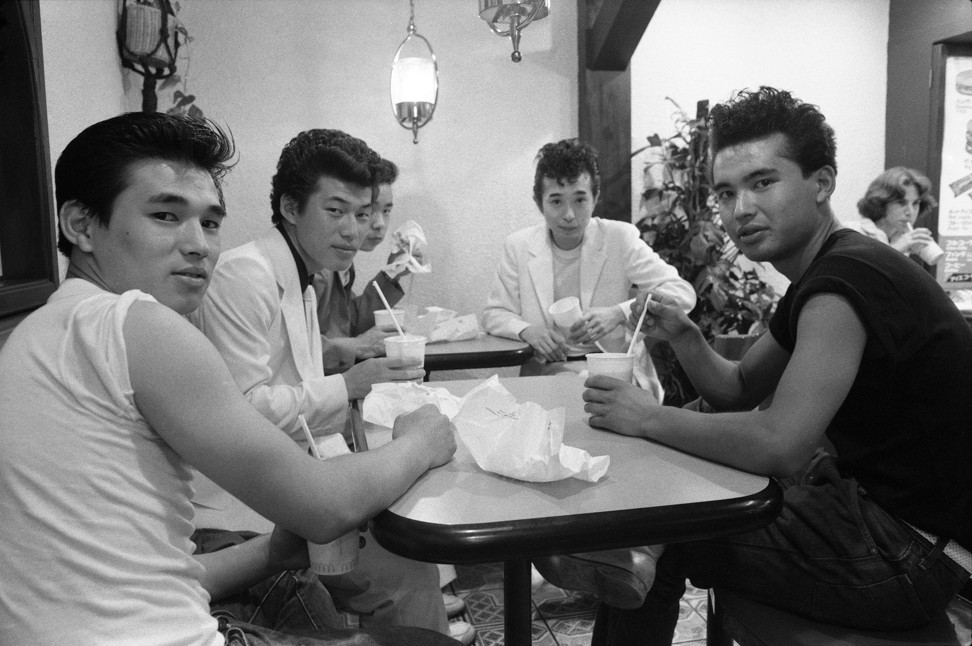

The seamy nightlife districts of Tokyo provided Girard with a setting for compelling, edgy portraits, as in his photographs of slickly dressed young gangster types and the denizens of local bars and nightclubs.

Girard’s photographs of Tokyo, however, paint a much wider and more nuanced picture of everyday life in the city than anything he had previously attempted. He presents an earnest, attractive, well-dressed young couple with two small girls waiting patiently for the bus on a crowded pavement.

He captures one of the nattily dressed “elevator girls” who figured as an attraction in Tokyo’s larger department stores, and shows us one of their not dissimilarly attired male counterparts, the city subway attendants.

He catches a man in a business suit gazing utterly transfixed at a wall teeming with lurid posters for yakuza gangster films and porn movies. At one of his regular late-night haunts, a 24-hour Mr Donuts shop in his Tokyo neighbourhood, he bends down to photograph a drunken off-duty sushi chef who is good-naturedly performing a “yakuza greeting”.

Not long after moving into his first apartment in Tokyo, Girard recalls lying in bed late one night, half asleep and listening to music on his transistor radio. Suddenly, he was startled to hear the United States national anthem begin to play and an English-speaking voice announcing, “You’re listening to American Forces Far East Network.”

He remembers wondering if he had somehow fallen into a time warp. “Oh yes, Japan lost the war, so the US gets to keep its military here – but wait, isn’t it 30 years since the war ended?”

He soon learned that an extensive network of US bases existed throughout Japan, many of them located in the Tokyo region, and that until the recent winding down of the Vietnam war, these bases had been the frequent target of Japanese anti-war protests.

Girard decided to pay a visit to the immense US naval base in Yokosuka, about an hour southwest of Tokyo, at the mouth of Tokyo Bay. There, in the home port of the US Seventh Fleet, he walked the streets, stopping US sailors and asking if he could make their portraits.

He quickly located Yokosuka’s notorious nightlife district (made famous as the setting of Shohei Imamura’s satirical 1961 film Pigs and Battleships), whose streets were lined with bars, nightclubs and brothels catering to US servicemen.

Yokosuka awakened Girard’s fascination with the odd particularities of America’s globe-spanning “base culture”, which became a recurring subject in his work.

Tokyo-Yokosuka 1976-1983 collects Girard’s photography of Tokyo, including during two extended periods of living in the city, in 1976-77 and 1979-80. The book is available at Blue Lotus Gallery, 28 Pound Lane, Sheung Wan; bluelotus-gallery.com ; and greggirardpictures.com .