At 9.55am every day since December, a German ICE high-speed train has left the Gare de l’Est in Paris headed, via Strasbourg, Karlsruhe and Frankfurt, for Berlin Hauptbahnhof, where – all being well – it pulls in just over eight hours later.

Remarkably, the service is the first direct, high-speed, centre-to-centre rail link between the capitals of the EU’s two biggest countries. Run by Deutsche Bahn (DB) and France’s SNCF, it has been hailed as a milestone in European train travel.

It is not the only new service linking Europe’s cities. From next May, the ČD ComfortJet, operated by the Czech, German and Danish railways, will carry you all the way from Prague to Copenhagen, calling at Dresden, Berlin and Hamburg, in just over 11 hours.

Major new routes are being built: a high-speed Alpine tunnel linking Lyon and Turin; the Fehmarn Belt connecting Germany and Denmark; Rail Baltica, which will join Tallinn in Estonia to Warsaw via Riga in Latvia and Kaunas in Lithuania.

On the face of it, then, high-speed, long-distance rail travel in Europe seems to be finally taking off. But in fact, fast, efficient cross-border rail services between the continent’s major urban centres remain, for all the media fanfare, very much a rarity.

For a whole raft of reasons – inadequate infrastructure, unwilling operators, incompatible systems, incomprehensible timetabling and (last but not least) impossibly complicated ticketing – long rail journeys across Europe are all too often a pastime rather than a practical travel alternative.

Imagine, for the sake of illustration (few except slow-travel aficionados would ever actually attempt it), a four-country trip from Spain’s second-biggest city, Barcelona, to Marseille in France, then on to Italy’s largest port, Genoa, ending in Ljubljana, the capital of Slovenia.

For starters, says Jon Worth, an independent writer and campaigner on European cross-border rail travel, while there is a high-speed line across the Spanish-French border, for most of the year it carries only four trains a day, and five in summer.

“Why?” Worth says. “Because the new trains run by the Spanish operator, Renfe, haven’t been approved to run in France, and SNCF has cut the size of its fleet capable of running in Spain. So the trains that do run are invariably packed, and prices are sky-high.”

Next, only one of those four or five daily trains will run direct from Barcelona to Marseille, and it arrives in France’s biggest port so late that you miss the last service to Nice, which is where you need to be in order to catch a train to Italy.

So, you must then board a slow regional train the next morning for the hour-long ride to Ventimiglia, followed, with luck and good timing, by a relatively fast intercity connection along the Ligurian coast to Genoa.

From there, things only get worse. Trains crossing the Italy-Slovenia border at Gorizia-Nova Gorica run at weekends only. Those doing so at Villa Opicina, near Trieste, are daily but very irregular. So the 370 miles (600km) to Ljubljana via Milan and Venice will take up to 13 hours and probably involve travelling via Villach in Austria.

“It’s one of the worst borders to cross anywhere in the EU,” says Worth. “Very few, very slow trains.” Moreover, although European night trains are making a much-hyped but in reality slow and difficult comeback, there isn’t one on this route.

(Actually, that’s not strictly true. The Espresso Riviera, operated by Treni Turistici Italiani, is a delightful upmarket sleeper service from Rome to Marseille and back. Unfortunately, it runs only in July and August, and then just once a week.)

Leaving aside the nonexistent connectivity, the obstacles facing the long-distance European rail traveller will have become apparent long before they actually get on a train. Planning a trip and buying tickets (as well resolving problems if things go wrong) are daunting challenges in themselves.

Seasoned travellers recommend Deutsche Bahn’s website as the best and most comprehensive planning tool for navigating the seemingly infinite complexities of Europe’s train schedules, but few novices would describe even that as user-friendly.

It is also unlikely to be able to sell you all the tickets you need, which will have to be bought separately from the various national operators. Unlike plane travel, through train tickets are rare – and if they exist, they are often more expensive than a combination.

Moreover, although services such as Trainline – which anyway only offers only a small selection of possible routes – can sell you a through journey from, say, Barcelona to Nice, it will be two tickets with two different operators, sold in one transaction.

“That means,” says Worth, “if anything goes wrong – say, a train is late and you miss your connection – you have no passenger rights at all. Worse, few stations will be able to help. Unlike in an airport, you’ll have to sort it out yourself.”

Across the continent, similar issues recur, vastly complicating journeys that could, in principle, be smooth, practical, sustainable travel alternatives – and pushing even those willing to accept a longer and more expensive trip on to Europe’s ferociously competitive airlines.

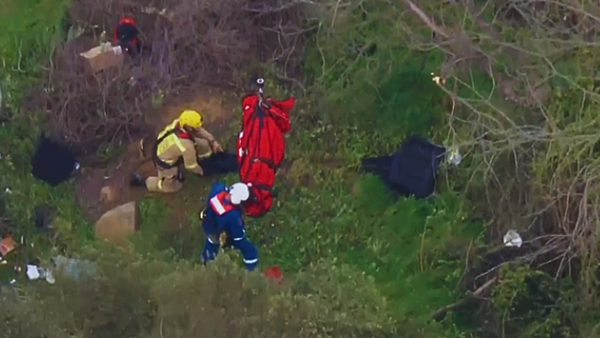

Sometimes, infrastructure is the main obstacle. French TGVs and Italian Frecciarossas link Paris to Milan in seven hours, for example, but must crawl through the Alps until the new Lyon-Turin high-speed line and tunnel is completed, theoretically in 2033. Meanwhile, the current route is heavily susceptible to damage from increasingly frequent landslides: after reopening in April following a 20-month closure for mudslides, it had to shut down again for several days in July for the same reason.

At other times, the issue is a lack of cooperation between rail operators. Astonishingly, there has been no direct train connection between Madrid and Lisbon – two neighbouring European capitals – since a Spanish sleeper service was discontinued in 2020.

The 450-mile journey now requires two changes and multiple tickets and takes more than eight hours. Lines are being electrified but there is no guarantee that Renfe and Portugal’s CP, which have very different strategies, will combine forces and deliver a through service.

“Operators still mostly think and work nationally,” says Worth. “CP is old-style, regular, but has only just started work on its first high-speed line. Renfe is modern, high-speed connections between Spain’s major cities. They’re just not a good fit.”

Different technologies and operating systems are a major block. In principle, that can be overcome with modern, multi-system rolling stock, but it is significantly more expensive. A pan-European signalling system, ETCS, is on its way but not there yet.

Other obvious European rail connections badly in need of upgrading, Worth argues, could include Berlin-Warsaw, which still runs on slow tracks for much of its six-hour journey (though that may change, given Poland’s ambitious high-speed rail plans).

And in Scandinavia, a high-speed service linking Oslo to Stockholm or Copenhagen remains a pipe dream. A project that would slash travel times between the Norwegian capital and Gothenburg in Sweden to an hour has, so far, made zero progress.