How the first world war began is just too important to get wrong. The millions of deaths, the world order realigned, the unleashing of nationalistic chauvinism, all remain of such cardinal importance that the historical record must be sound. Or so I thought.

So legion are the mistakes in the reckoning of the moment that sparked the fighting – the 1914 Sarajevo assassination of the Archduke – that I felt driven to act.

For a century, people have been getting it wrong, from the first hawkish Habsburg investigators prone to political prejudice, to sloppy BBC documentary research. A recent account of the assassination by Max Hastings (and God strike me down for pointing out mistakes by a man who once gave me a job in journalism) is holey with errors.

So a drive to put this right was one of the forces behind my latest book The Trigger –The Hunt for Gavrilo Princip: The Assassin Who Brought the World to War. Off to the archives I went, panning for nuggets of verifiable fact, sluicing away inconsistency and occasionally uncovering gleaming new material.

But my aim was not simply to present the most definitive account. If I did that alone, I would become, in the words of my wife, “nothing but a pub bore on a Balkan killing”.

What I wanted to better understand was how such an important historical moment could be so misrepresented. And to do that, I needed to spend time on the ground.

My previous books have used the device of journeys to unravel history: a traverse of the Congo in Blood River to sense Africa’s failed potential, a trek through the ebola epicentre Sierra Leone and Liberia for Chasing the Devil, to gauge the margin between survival and growth.

It is a deliberate attempt to shape a fresh literary genre: books that are not travel books alone, nor adventure stories, nor authoritative histories, nor polemics, but somehow a blend that takes in all of the above and, I hope, more.

To follow the life of the 1914 assassin, Princip, from his remote rural birthplace in Hercegovina to radicalisation while at school in Habsburg-occupied Bosnia and “liberated” Serbia, and ultimately the street corner in Sarajevo where he fired his 9mm Browning pistol, was a powerful journey.

The land he passed through remains wild and charged. I walked the hills and valleys in 2012, glimpsing at one point that most powerful of wilderness symbols, a wolf, and later witnessing the burial of 500 victims of ethnic violence from the 1990s.

It brought home the shape-shifting nature of history. The spot where he fired has had numerous plaques over the years, a shrill one condemning him as a murderer, the next praising him for liberating all local Slavs, another lauding him as killer of Germans, the next claiming him as a communist hero.

It taught me that although some of the slip-ups in the received history are inconsequential, others are paramount. The casus belli of the first world war, namely that Austria-Hungary was justified in attacking Serbia in “retaliation” for the Sarajevo assassination, is not supported by evidence.

And the land that gave us the boy who triggered the first world war is still giving. Young Muslim outsiders, many from Britain, went to Bosnia in the 1990s, the first stage on a jihadi radicalisation that led directly to the horrors of 9/11 and today’s cruelty in the Middle East.

Can I forgive those who muddle their accounts of the 1914 assassination? Of course I can, knowing what I know now about the way history can be massaged. The dictum sometimes attributed to Napoleon needs to be remembered: history is nothing but the lies that are no longer disputed.

Extract

This story springs from many sources, but the most powerful one for me was the discovery I made at a street market in Sarajevo, back when the city was under siege in 1994. I was a young reporter sent by the Daily Telegraph to cover the Bosnian War, which had begun two years earlier in this land of mountain and myth. Shelling had often made it too dangerous for civilians to venture outside in their capital city, but during a lull in the firing I joined locals as they reclaimed the streets. One afternoon I walked into an open area busy with people reduced by the war to selling possessions laid out in piles across unswept pavements. Pickings were meagre: half-worn brake pads from cars that had not run in years, a set of taps unused because of no mains water. I took a photograph of an elderly man sitting under an umbrella, shaded from the July sun, as he sold cigarettes one by one.

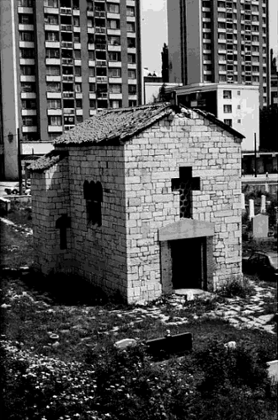

And then I noticed people occasionally slipping away from the market to visit a stone building on the edge of a nearby cemetery. I went to explore.

It was about the size of an electricity substation, a modest structure with a box design, easy to overlook. It wore the livery of so many wartime buildings in Sarajevo: a cavity from what appeared to be an artillery strike, terracotta roof tiles rucked out of alignment, the door ripped from its hinges, its frame pock-marked by shrapnel. I followed the market-goers and, in the summer heat, my sense of smell told me from some distance what was going on. They were using it as a makeshift lavatory. My diary recorded it in malodorous detail:

The graveyard was unkempt but I was not prepared for what I found … The floor was just a sea of turds. Amongst the mess were dozens of used sanitary towels, a bra and lots of rubbish. A tombstone lay smashed in two on the floor and the light hung wrecked from the ceiling which had a gaping hole in it.

But what made me curious was that the building was clearly some sort of chapel. A cross was visible above the doorway. Why be so disrespectful of a religious site?

I found the answer on a piece of black marble set into an external wall. It was a commemoration stone bearing the date 1914 and some cyrillic text, including a list of names. At the top of the list, in the most prominent position, was one that jumped out at me: ГАВРИЛО ПРИНЦИП, Gavrilo Princip.

More about The Trigger

“A tour de force … a masterpiece of historical empathy and evocation. Princip is the focal point of Butcher’s book, but its true protagonist is a Bosnian memoryscape that shimmers between past and present.” – Christopher Clark

How to buy The Trigger

- The UK paperback is published by Vintage at £9.99 and is available from the Guardian bookshop at £7.99

- The US paperback is published by Grove at $16