We all make different choices: we go on different holidays, paint our bedrooms different colours and choose different types of pets.

The soup of humanity consists of many different chunks, and no one person will lead the same life as another. Which, of course, we all know and freely discuss.

But one of the more taboo questions to ask polite company (beyond marital problems, income, whether they have a foot fetishes, etc) is: why did you decide to have the number of children that you did? Or to not have any at all?

You may feel you can’t ask because it’s a fragile topic — one that can be fraught due to fertility problems and strife, quiet struggles and unspoken traumas.

As diving into the discourse with such a question would be rude, it becomes even more intriguing. How do people choose how many children they’d like to have, and is there, really, an ideal number?

For Londoners, in 2024, the birth rate stands at 1.35, below the national average of 1.44 (falling from 1.8 in 1992), with a variety of reasons being cited for the fall, from childcare costs and housing prices, to women waiting longer to try and get pregnant.

Studies, too, don’t seem to provide any clear answers — one piece of research from 2005 states that having one child boosts happiness, while a second can negatively affect the mother. Another study claims that having two children, in the long-term, is beneficial for your wellbeing, but that having three isn't.

Another states that having either one or four is terrible but two or three is just right. In effect, you can find a study that says whatever you want it to say.

And so, I thought I’d ask a chatbot how many children was considered an ideal number and even it was angry with me for asking. Of course there isn’t an “ideal number!” it insisted. “It is a profoundly personal choice and everyone’s views and circumstances differ!” it added.

So instead I turned to my own network — those I know with none and up to three children, to see why they chose the number they did.

I was careful to only ask those who I knew to have made a choice with their number — those I was sure hadn’t been troubled by infertility or illness, or had the decision taken out of their hands in other ways.

My childless (by choice) friend explained how she wanted her life to remain truly hers, and had a lack of desire to lead the life of a parent: "The way I saw it, having kids just seemed like drudgery and I didn't think I'd enjoy it — at all."

A relation with one child described the freedom that stopping at one brought for her career and relationships, and how "it felt like we'd be spreading ourselves really too thin if we [were] looking to have more kids, and be able to focus on our personal lives, our relationship, and also our professional growth.

When it came to two children, a friend highlighted the importance she felt for her children to have companions and allies, but believed that "families with lots of children end up getting ignored, fighting for attention, and [can] grow up feeling very lonely."

You have to have a slight spark of insanity to keep you going in parenting

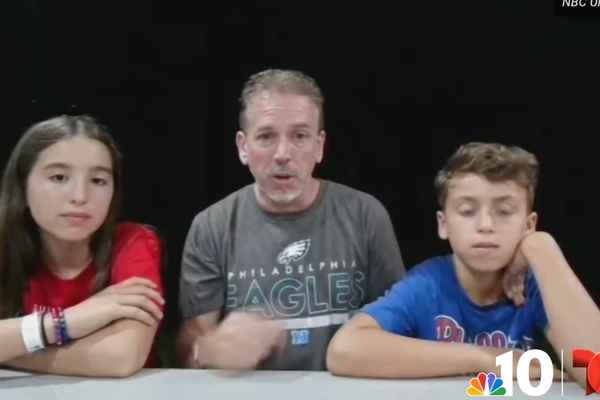

And as for three children, my ex-colleague lit up as she explained the wonders of having a little team around her, and the joy that she found on days like Christmas or Halloween. “I think about it in terms of, what would I like my life at 65 to be like?” and that, for her, means the dream of having a bigger family, was worth all of the chaos, and tasks, and money (currently the cost of a raising a child until their 18th birthday stands at £260,000 in the UK).

Ultimately, what it seemed to come down to was: how delusional are you? (Bear with me). Like many things, you have to have a slight spark of insanity to get you through the hardships — the frustrations, the sleepless nights, the loss of personal time, the financial hardships.

Just as with marriage, or dating, faced with a situation that is in many ways, a risk, we need to have a slightly unhinged level of optimism when we have kids.

As my friend without children explained: “You have to be passionate about it to get through the tough bits of [parenting].”

The rewards a person finds in parenting — the moments of magic, the laughter, the first time your child puts their trousers on (backwards) — all need to outweigh the financial, practical, and onerous elements of parenting. Without this passion, or this dash of ‘madness’; the full scope of negatives comes to the forefront.

What I found out through my conversations, was that once people had reached their limit of children they wanted to have, the prospect of another one seemed littered with gambles they didn’t want to take, and concessions they didn’t want to make — a too-crowded house, more money spent on childcare, another career break they weren’t keen on.

My childless friend asked the reasonable but lesser-discussed question: what if you don’t like your children? And my relation with one child equally brought up the often-ignored fact that sometimes siblings don’t even get along. The risks and compromises that go into having multiple children are often overlooked because for many of us, our drive to have families propels us through the trickier elements, as it’s something we deeply want to do.

Read more: It's a (sob) boy! I know how gender disappointment feels

So, what is the ideal number of children? It turns out that my chatbot was correct — there isn’t any specific number that can be decreed as ‘ideal’. There’s no exact figure that is guaranteed to make everyone more happy, or less happy, and it all stems from your own life, circumstances, and outlook.

The number is as far as the mist of idealism will take you to cushion the blows of the mundane drudgery. The happy place where the desire to have that specific number of children outweighs all the times that they call you names and watch you pee.

A certain Venn diagram in which your passion for parenting, hopes for the future, and patience for being sprinkled in food overlap: that’s where your ideal child number lies.