ITV’s new drama Coldwater boasts possibly the most inadvertently comical opening 20 minutes ever. It’s also, in the current TV climate, very telling. In how many different ways can it be explained that Andrew Lincoln’s John is a troubled, weak, vulnerable man? He runs away from a violent incident in a playground so fast that he forgets one of his kids. He can’t face the prospect of sex with his wife. He gets bullied by a man in a petrol station. He is browbeaten by his new neighbour. He has an encounter with a psychiatrist, which is less an insight into his shrivelled soul than a signifier of it. Why? Because he’s a troubled, weak, vulnerable man! Got it? Then we can proceed.

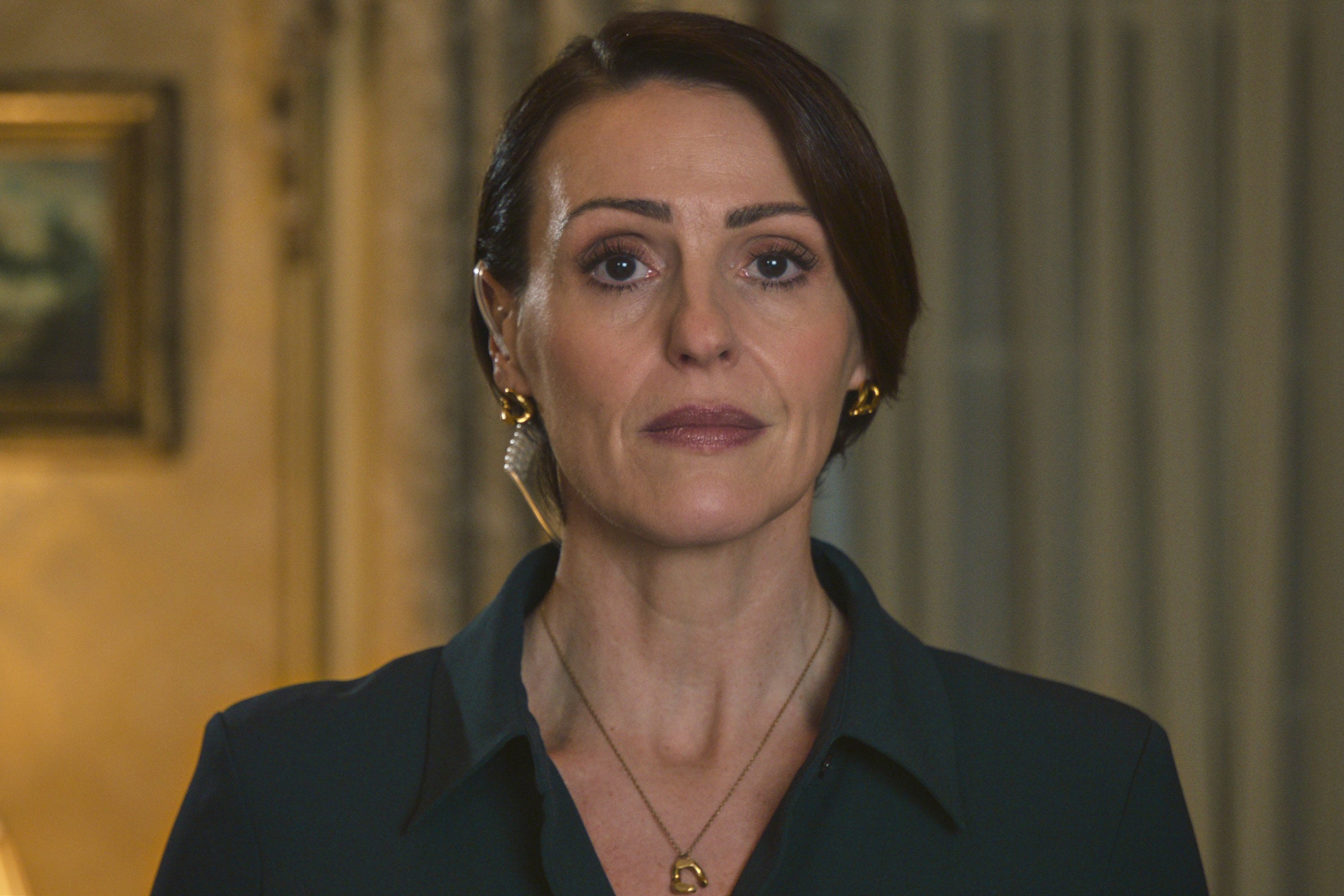

This kind of nuance-free exposition is becoming dangerously common in television drama. You might also recognise it, for example, at the start of Netflix’s political thriller Hostage. Suranne Jones’s ambitious minister Abigail Dalton is discussing the possibility of running for the top job with her husband Alex (Ashley Thomas). But she has a concern. Might a moment arrive when Abigail is forced to choose between the best interests of her family and the correct professional course of action? “If it ever comes down to a choice,” says Alex soothingly, “you’ll make the right one.”

You’ve probably heard of Chekhov’s gun (if there’s a gun on the wall in the opening scene, in the second or third act it must be fired). But this is Chekhov’s blunderbuss: a wild, unsubtle spraying around of foreshadowing so insultingly obvious that it pretty much gives viewers the excuse to check out and look at their phones for the next 10 minutes until the first hints about the exact circumstances in which Abigail is going to betray her family start to arrive.

Speaking to The Hollywood Reporter in 2023, filmmaker Justine Bateman spoke of showrunners being given notes about scenes not being “second screen enough”. It feels as if we’re now starting to see the effects of this pandering to damaged attention spans. And it isn’t just drama either – many documentaries and reality shows now have an attenuated quality; a sense of dilution; a lessening of effect. But how did this happen?

It’s a development with a range of causes. Paradoxically, it has its roots in the so-called golden age of TV dramas. Shows such as The Wire, Mad Men and The Sopranos demanded space. They were expansive in ambition and also in size. They also demanded viewers’ full attention, but their scale segued neatly into the streaming era, which promised unlimited dimensions in which to tell sprawling stories. It hasn’t really worked out that way, though; instead, it’s heralded the era of the binge watch.

Scroll TV is the endpoint of the binge watch, which has already devalued so much of what we see on screen. It is TV as an endless bag of Haribo Tangfastics. Keep scrolling, keep watching. You know you want to. You’ll feel terrible afterwards when the sugar rush has passed – like you’re full to bursting but you still haven’t had the nourishment you need. But that’s a problem for tomorrow.

It’s no coincidence that the rise of scroll TV coincided with the full-season dump era. Pioneered by the streamers, which themselves were likely inspired by the box-set phenomenon, the trend of dropping a whole season of episodes at once has now largely been adopted by the BBC and ITV, too. Much rarer are the water-cooler shows we wait for every week, such as Line of Duty or Happy Valley. When 10 episodes of a show arrive simultaneously, it’s bound to alter the writing. Scarcity and deferred gratification are no longer a consideration. Cliffhangers exist solely as an inducement to viewers to press the button marked “next episode”. In between cliffhangers are hours of directionless tease. But when we gained the ability to shotgun a full season of Stranger Things in a single weekend, we lost something, too. An unhealthy proportion of shows now leave barely a trace, just a faint scar on your algorithmic self.

Covid was also an accelerant to this process. Lockdown opened up huge swathes of empty time that were previously occupied by our working and social lives. However, if anything defined that weird period, it was distractedly watching rubbish TV while doomscrolling endlessly. Why did Netflix’s Tiger King do so well? It was a strange but abstracted story; striking enough to briefly hold the attention but low-stakes enough not to really matter.

And isn’t this basically a perfect description of dramas like Coldwater, The Hostage and the BBC’s hysterical, somewhat farcical thriller The Guest. They’re superficially entertaining, but they don’t really exist to illuminate anything profound about the human condition. Instead, they use the signifiers of quality – excellent casts, high production values, a general impression of weight and seriousness – to skim the surface. After all, if things are left open-ended, there might be a second season to be had.

However, there are already a few signs of a reaction. It’s often lazily assumed that short attention spans are a problem largely affecting young people. This phenomenon challenges that idea. After all, who are these dramas aimed at? Not the under-thirties, surely?

In fact, young people in the online sphere are more than capable of prolonged bouts of concentration – and of doing things for themselves. Dip your toes into the world of video essays on YouTube. You’ll find a fascinating world of original, expansive, DIY filmmaking. For example, YouTuber Hbomberguy’s complex, entertaining, carefully argued and nearly four-hour-long film about online plagiarism has been viewed 38 million times. Maybe scroll TV is the end of something old? As television mutates, perhaps something new is on the horizon?