Millions of Americans will be traveling this Thanksgiving weekend – a good chunk of them faced with a gloomy nor’easter. These times of heavy travel and weather disruptions remind us how reliant we really are on our transit systems. But that’s something John O’Grady never, ever forgets. His job is to keep the stormwater that can paralyze those systems out.

O’Grady has worked for 26 years at New York City’s Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) as a manager of infrastructure and facilities projects – he knows the nuts and bolts of how New York City subways run. But when the MTA faced a series of flash floods in 2007 and then Hurricane Sandy hit in 2012, his job changed currents. That’s when New York transit realized they needed a whole department dedicated to long-term flooding prevention.

“I was never, and don’t profess to be, a flood or stormwater or hurricane expert,” he told me. “The day after Sandy, this work pretty much found its way to me.”

For my Stormproofing the City series, O’Grady explains, in simple terms, how he’s protecting his transit system – one of the world’s oldest, biggest and busiest – from future natural disasters.

What are some ways you’ve been making the system more resilient?

So you’ve been speaking with people with a more global, city-wide picture. Keep in mind that my work is specific to New York City Transit.

We can’t stop a hurricane. What we can do is protect the transit infrastructure, because our system can’t go down for a couple weeks. We need to start moving the city again as soon as the storm has passed. And to do that, we have to make sure the yards don’t flood, that under-river tunnels don’t flood, that stations don’t flood, etc.

So we look at ourselves as being responsible for our own fate. It’s been two years and we’re just finishing the planning phase – there’s still a lot of work to do. But we can’t wait for some of the more global strategies to be implemented.

This is interesting, because a transit official wrote in to the series to suggest that “there is no appearance of coordination between the MTA and NYC, and hundreds of millions of dollars are being spent on redundant projects.”

I wouldn’t call them redundant. Fifty years from now you may be able to say that, but until there’s a global strategy for the overall city, I think the MTA is being smart.

There’s always the potential for overlap, but sometimes you have to fix things while you’re waiting for that overlap to materialize. And I think the best course of action is for each of these agencies, like Con Edison, Transit, and the Department of Environmental Protection, is to go about fixing and hardening their systems while the global approach works through its necessary environmental and funding processes.

Someone with a more global perspective could say, “Why is Transit doing that? We’re going to do it in the next year or two.” But it won’t be the next year or two. It takes longer than that.

Can you tell me about a few of the floodproofing projects you’re planning for the subway?

The approach for MTA is to keep the water out. First you have to know where you can possibly flood, so we imposed flood mapping over our transit system to identify our most vulnerable assets. Then we figured out how to best keep water from destroying or coming through those assets to flood the system.

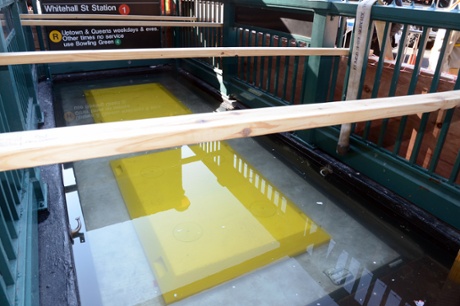

Assets are things like ventilation bays – the grating on the sidewalk that people walk over every day, which allows for the natural exchange of air between the subway and the street above. Those wind up being an extreme vulnerability in floodprone areas. There are also the manholes on the street, equipment hatches on the sidewalks, and emergency exits for underground evacuation. None of these are watertight.

We’ve developed a structure for the vent bay, for example, that’s like a bottomless box that allows air through day in and day out, but that allows us to release a pin that closes the bottom, keeping water out should there be a storm.

How did you create these solutions for keeping water out? Did you look to other cities?

Honestly, one of the first things we did after the storm was a worldwide survey of all transit systems to see if any brilliant idea existed that we hadn’t thought of. And we didn’t find any innovative solutions by exploring what’s used in Tokyo or Hong Kong or Europe or South America. Generally, the systems prone to flooding pretty much use the same technologies we were proposing.

Then, when we looked at the floodproofing technologies available, we couldn’t find any that existed for the kinds of facilities that Transit has. So we had to work with vendors to develop or adapt their technologies to our system. This has really been a significant effort.

Here’s one example: we worked with a vendor to develop flexible closure panels for station staircases. That lets us close off a staircase, which normally could allow water to flood the system, by deploying a hi-tech strong curtain material across it horizontally.

Where does the money come from to pay for these projects?

It comes from the Federal Transit Authority. We’re still in the design process – with a couple years of implementation to go – so how much money we’ll need is still being determined.

And there are always going to be projects that you can’t get to. But I do believe that Transit’s most vulnerable areas can be made to sustain a similar event to Sandy. The system will remain vulnerable, however, as we put these remedies in place.

So if another storm like Sandy was to happen tomorrow, nothing will have changed yet?

We’re pretty much still in the initial stages of implementation. We’ll be awarding a slew of projects for lower Manhattan locations over the next few months, and they’ll be in construction for the next year or so.

In the end, I’m certainly expecting to get this work into place before another Sandy-type event. But it does concern me.

Our operating department has plans for how to temporarily protect these most vulnerable locations should another storm suddenly appear. They can barricade entrances, like they did with Sandy – and they’ll build higher and stronger ones in the future. Certainly Con Edison is hardening their system. And we do have pumping capability, if water starts to come into the system on a gradual basis.

The problem with storms as big as Sandy is the volume of the surge and the floating debris, which can include massive objects – like dumpsters. When a marine timber 30ft long traveling in a moving current of water barrels into a wooden barricade, that trumps any temporary defense we can put up. During Sandy, even the power was out. There wasn’t a fighting chance.

Are you working to protect the system against storms like Sandy, or bigger?

We’re protecting for a storm that’s a degree stronger than Sandy. Two to three times more powerful, the city’s gonna be in trouble. But for a storm a grade up, we’ll be fine.

When I spoke with scientist Klaus Jacob, he suggested we consider bigger and longer-term solutions, like raising the entrances of the trains, or raising the trains themselves. Can you imagine working on something like that?

I actually can’t. To raise or build a new line so you’d never flood again would be a significant investment. And it’d be many years of environmental and funding processes – I don’t know if we’d ever have the money for it.

Is that an approach that works? Absolutely. Is it necessary? Not yet. I understand that his job is to anticipate the things we may have to face in 20 years, but for right now my team just needs to focus on existing facilities – we simply don’t have the dollars to rebuild the system.

What’s the biggest challenge your team faces?

It’s the fact that we have so many riders that depend on us. Rush hour is now every hour of the day, so we have to be careful about upsetting the general path of commuting New Yorkers. But to do this work, we have to take trains out of service. If I had a magic wand, I’d love to fix all nine of our under-river tubes at the same time, but it’s not practical. We have to do one or two at a time. And that drags the schedule out.

This is making me feel bad for cursing MTA during weekend service outages.

Yeah! Folks like to be able to walk to their station and take the train. If they’re used to a path of travel, they get upset when they don’t have it – even if another is just as convenient. But it’s important to remember that we have to close off these areas to keep the public safe and make the system stronger.

We’re working our way through this, and we’re working as fast as we can.

This interview is part of a series called Stormproofing the City.