America loves cowboys so much, we even love them when they’re not cowboys per se. The tropes of American westerns transcended the genre long ago, and even after its spaghetti western heyday we still craved heroes who lived the cowboy lore. We love wide open space, plainspoken protagonists, and a black-and-white moral code that lets us tell the good from the bad from the ugly. So it's not a surprise that when one of gaming’s most iconic developers applied these tropes to one of our modern cowboys — an outlaw biker — something magical happened.

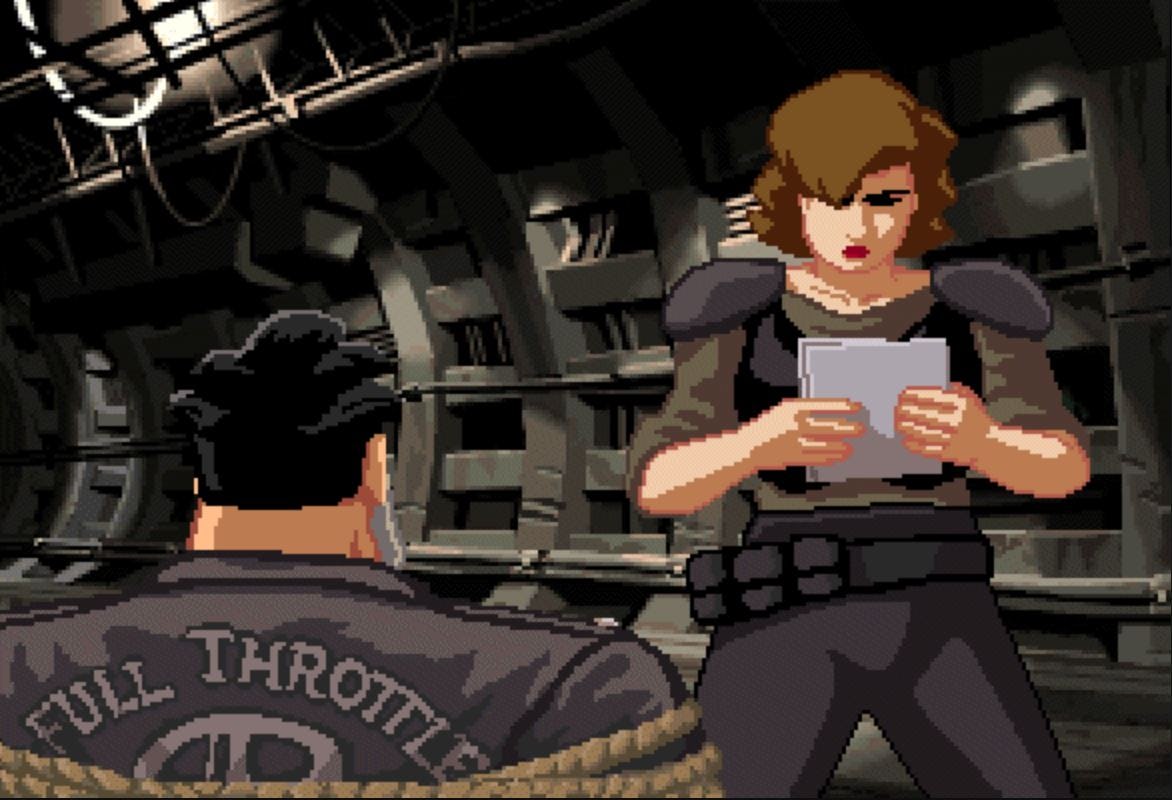

Released on May 19, 1995, Full Throttle stands as one of LucasArts’ most iconic point-and-click adventure games. Unlike its peers it wasn’t a game about mind-bending puzzles or a long, plodding adventure over dozens of hours. Instead, Full Throttle had a commitment to cinematic storytelling, a punk-rock aesthetic, and a pivotal role in the legacy of LucasArts’ creative heyday. As a narrative-driven, biker-noir odyssey helmed by Tim Schafer, Full Throttle captured a very specific slice of American counterculture while nudging the adventure genre toward something more emotionally resonant and visually ambitious.

At its core, Full Throttle is a story about loyalty, rebellion, and the slow demise of the open road. You play as Ben, the gruff yet principled leader of the Polecats. Your motorcycle gang is caught in a conspiracy surrounding Corley Motors, the last bastion of American-made bikes in a world shifting toward soulless minivans. When the company’s idealistic founder is murdered by his conniving vice president, Ben is framed. Now you have to clear his name, protect his gang, and preserve the spirit of biker culture from corporate rot.

Narratively, Full Throttle is an anomaly for its time. Most adventure games of the era leaned into whimsical or surreal worlds (Day of the Tentacle, Sam & Max Hit the Road), but Throttle was grounded in grit and mythos. It fused Mad Max-style post-apocalypse with Route 66 Americana, punctuated by tight dialogue, cinematic pacing, and a sick licensed soundtrack from the biker rock band The Gone Jackals. The voice acting — featuring Roy Conrad as Ben and Mark Hamill chewing scenery as the villainous Ripburger — was top-notch. These performances gave the game a weight that few contemporaries could match.

Mechanically, Full Throttle was a mixed bag, albeit a fascinating one. Schafer and team pared down the traditional LucasArts interface into a minimalist “verb coin” system. It’s a radial menu with icons for eyes, hands, mouths, and feet that was designed to streamline interaction and make the experience feel more natural and intuitive. It worked … most of the time. While this allowed for quicker engagement with the world, it also limited the complexity of puzzle-solving. This frustrated players at the time who expected the intricate chains of logic that defined the 90s point-and-click adventure game genre.

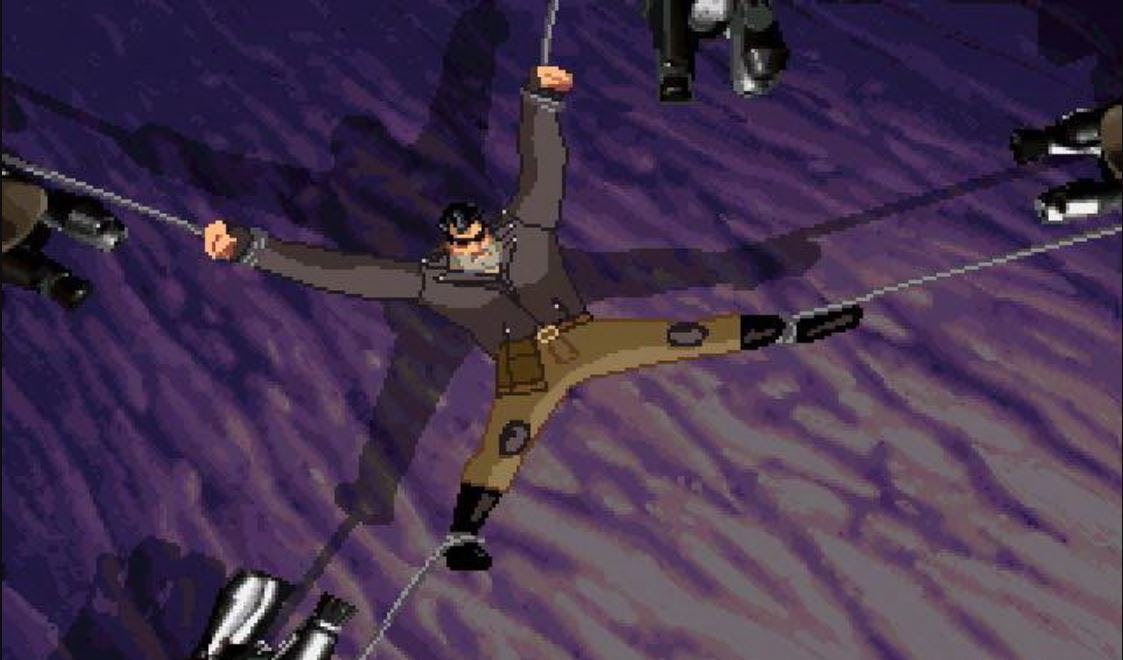

More divisively, Full Throttle experimented with non-traditional gameplay sequences, including action-heavy motorcycle combat and a demolition derby. These segments, while ambitious, were often clunky and felt disconnected from the otherwise smooth narrative flow. Still, their presence marked a turning point: Schafer’s desire to blend genres and challenge the limits of what a “graphic adventure” could be.

Critically, Full Throttle was well-received for its storytelling and presentation but faced scrutiny for its brief playtime (under 10 hours for most players) and its departure from puzzle-heavy norms. Commercially, it did well, but not spectacularly. Plans for a sequel, Full Throttle: Hell on Wheels, were scrapped in the early 2000s, a casualty of shifting market trends and studio infighting.

In retrospect, Full Throttle is less important as a game and more significant as a cultural artifact. It represents the last era where LucasArts, unburdened by the demands of Star Wars tie-ins, took creative risks with original worlds. Schafer would leave the company shortly after to found Double Fine Productions, where he’d continue pushing narrative boundaries with Psychonauts and Broken Age. Meanwhile, LucasArts increasingly pivoted away from adventure games entirely, marking the end of a golden age.

Yet Full Throttle refused to fade quietly into nostalgia. A remastered edition in 2017 introduced the game to a new generation, with updated visuals, cleaned-up audio, and the option to toggle between classic and modern modes. While it didn’t reinvent the game, it reaffirmed its place in the canon of influential interactive storytelling.

Today, Full Throttle stands as a flawed but fearless work. In an era increasingly defined by sprawling open worlds and games-as-service models, its focused narrative and strong sense of identity have the same rebellious spirit as Ben and his gang. Full Throttle still echoes with the sound of a studio that once dared to ride its own road.