Jota Ishikawa, a professor of International Economics in the Graduate School of Economics at Hitotsubashi University, spoke with The Yomiuri Shimbun about U.S. President Donald Trump's protectionist policies and their negative effects on the global economy. The following are excerpts from the interview.

Tariffs as bargaining tool

Ishikawa: In the United States, the Trump administration has launched a series of protectionist policies. They were a major point of discussion at the Group of Seven's Charlevoix Summit held in Canada. There are concerns that the impact may also extend to Japanese companies in the future.

[In March, the United States rolled out import restrictions that hiked tariffs on steel by 25 percent and on aluminum by 10 percent. A 25 percent increase in the tariff on imported cars is also under consideration.]

Ishikawa: What surprised the world was the initial announcement by the United States that all countries would be subject to the increased tariffs on steel and aluminum. The United States has claimed that this is because rising imports threaten national security. It is applying the same logic to the tariff on imported cars.

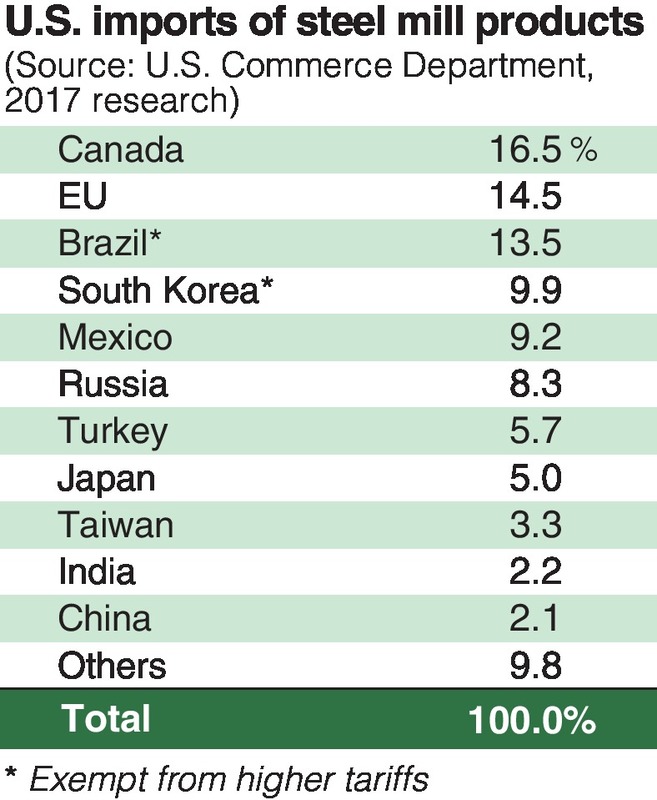

However, the United States later temporarily postponed the higher tariffs on steel and aluminum for six countries and one region, including Canada, the European Union and Brazil.

Ultimately, higher tariffs were imposed on all but four countries including South Korea and Brazil, starting in June. However, the share of imports from the initial six countries and one region accounts for more than 60 percent of the volume of steel and roughly 50 percent of aluminum. If they were in fact being considered for possible exemption, using national security to justify the move doesn't seem to make sense.

The Yomiuri Shimbun: Will this affect negotiations for bilateral free trade agreements?

A: President Trump's approach to negotiations is characterized by making threats against the other party and trying to put together a "deal" that is good for the United States, if only minimally. The temporary postponement of the tariff hikes appeared to have also been intended as a ploy to extract favorable terms in free trade agreement negotiations. In fact, South Korea was forced to make concessions, such as placing a limit on the volume of steel exports to the United States in exchange for the exemption from tariff hikes.

The Trump administration is likely to press Japan to negotiate a bilateral free trade agreement in the future as well. Tariffs on imported cars could possibly be used as a tool in the negotiations.

Lessons from 1929, WWII

Q: How will Japanese companies be impacted?

A: For steel and aluminum, the impact on Japanese companies will be limited for now. The majority of Japanese products are high-quality items that companies in other countries lack the capacity to manufacture, so U.S. companies will have no choice but to buy them even if tariffs rise, meaning that the harm will be felt mainly by U.S. companies. No more than about 2 percent of Japan's steel production is exported to the United States.

However, in general, when a country with an economy on a scale as large as the United States imposes tariffs, worldwide demand for steel typically declines and the price falls. If the steel shut out of the United States flows into places like Asia, it will compete with Japanese products.

If tariffs on automobiles are raised, the blow to Japanese companies will be much more severe. If South Korea is exempted, as with steel and other tariffs, the competitiveness of Japanese cars in the United States will drop significantly.

Q: What impact will it have on the global economy?

A: The even greater concern is that retaliatory measures against U.S. trade restrictions taken by China and the EU, among others, will lead to the spread of back-and-forth retaliation worldwide.

In the wake of the 1929 Great Depression, when the United States raised tariffs to protect domestic industries, other countries imposed retaliatory tariffs. This led to "bloc economies" that shut out foreign goods in many countries, and triggered a race to devalue currencies to boost exports. World trade volume shrank to a third of its former size in roughly four years. The global economy fell into a severe recession, which was a contributing factor behind World War II.

In this instance, I don't believe that countries will push through tough measures like those after the Great Depression. However, if import restrictions proliferate among countries, the impact will be greater than in the past. This is because globalization has caused industrial operations to be dispersed around the globe.

For example, in the case of Chinese companies importing parts from Japan to assemble products for export to the United States, if demand for Chinese products falls due to U.S. import restrictions, the sales of Japanese parts manufacturers will also fall. International supply chains mean the effects will span a wide area.

Reviving WTO essential

Q: What measures are available to oppose protectionism?

A: To oppose U.S. protectionism, the one public organization Japan can rely on is the World Trade Organization.

In the past, the WTO has succeeded in swiftly settling disputes. When U.S. President George W. Bush imposed a tariff of up to 30 percent on steel in 2002, the WTO decreed it a violation of the rules and permitted retaliatory measures by exporting countries. When the EU announced its plan to impose retaliatory tariffs on imports from the United States, the United States repealed the tariff.

However, there are currently vacancies on the WTO's Appellate Body, a dispute settlement organ equivalent to a superior court. Dismissive of the WTO, the United States is obstructing the filling of these vacancies, rendering it difficult for adjudication to make progress. Japan must diligently appeal to the nations of the world to restore its faculties by means of filling the vacancies of the Appellate Body.

Numerous studies have found that protectionist policies by the United States negatively impact the U.S. economy. This was evident during the friction between the United States and Japan over auto imports in the 1980s. There is no cure-all countermeasure, but it is critical that the Japanese government and business community cooperate with industry groups and nations facing disadvantages in the United States, and insistently appeal to U.S. public opinion: "Protectionism does not benefit the United States."

-- This interview was conducted by Yomiuri Shimbun Staff Writer Makoto Fukumori.

-- Jota Ishikawa / Professor of International Economics in the Graduate School of Economics at Hitotsubashi University

He received his B.A. and M.A. from Hitotsubashi University and his Ph.D. in Economics from the University of Western Ontario in 1990 in Canada. He has been in his current position since 2001.

Read more from The Japan News at https://japannews.yomiuri.co.jp/