“Do they know it’s Christmas?” the musician Bob Geldof once asked. Nearly three decades on, the answer in the United States is that they know perfectly well, but what that means, and how they express it, is in flux.

For years, conservatives have warned of a “war on Christmas.” Former President Donald Trump adopted it as a major cause, and nearly four in 10 Americans said in a poll last December that politicians are waging a campaign to take religion out of the holiday. Liberals have scoffed at the idea that anyone is trying to downplay Christmas, dismissing the whole thing as either earnest paranoia or cynical politics. They are right that there’s no coordinated push to downplay the holiday or its religious roots, but conservatives aren’t reacting to nothing: Christmas is becoming less of a religious holiday for millions of people. If a war on Christmas exists, it’s gaining ground in a long battle of attrition.

Americans still love Christmas, if not quite as much as they used to. In 1995, 96 percent celebrated the holiday, per Gallup; by 2019, that had dipped slightly, to 93 percent. What has changed significantly is the way people mark it. From 2005 to 2019, the portion of Americans who say their Christmas celebrations are “strongly religious” dropped from 47 percent to 35 percent. (The group that says its celebration is “somewhat religious” has stayed pretty stable, going from 30 percent in 2005 to 32 percent in 2019.) A majority of Americans are still willing to accept Christmas displays on public property (at least when they’re combined with Hanukkah displays), but that number sank from almost three-quarters in 2014 to just two-thirds in 2017.

For Trump, one of the key elements of the war on Christmas was a supposed unwillingness to say “Merry Christmas,” as the phrase has been replaced by more inclusive but less explicitly Christian phrases. “If I become president, we’re going to be saying ‘Merry Christmas’ at every store,” he promised in 2015. “You can leave ‘Happy holidays’ at the corner.” And after Trump’s victory in 2016, his former campaign manager Corey Lewandowski proclaimed, “You can say again, ‘Merry Christmas,’ because Donald Trump is now the president.”

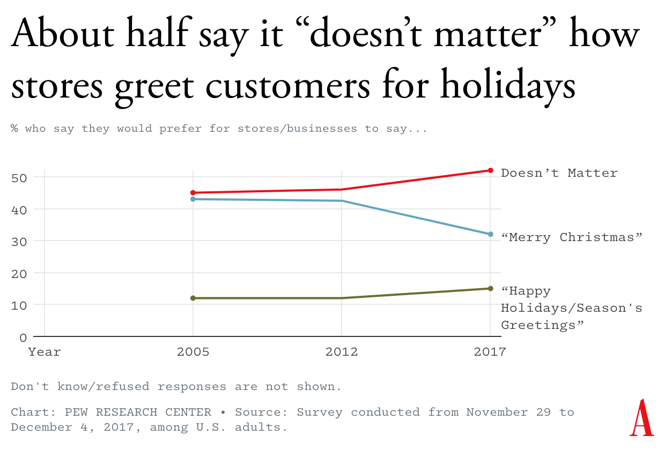

It appears that people weren’t afraid to say “Merry Christmas.” They just didn’t care. A real shift has occurred, not because of animosity but because of apathy. In 2005, roughly equal portions of Americans told Pew Research that they wanted stores to say “Merry Christmas” and that they didn’t care what stores said (with another 12 percent favoring “Happy holidays” or “Season’s greetings”). Over the next decade, those numbers diverged. By 2017, less than a third (32 percent) preferred “Merry Christmas,” while more than half (52 percent) said it didn’t matter which greeting stores used.

When people offer a holiday greeting, do you hear what I hear? It depends a lot on where you live and with whom you’re speaking. FiveThirtyEight, drawing on data from the Public Religion Research Institute, showed sharp regional differences in a 2016 analysis. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the West and Northeast, generally more liberal areas, lean toward “Happy holidays” over “Merry Christmas.” It is not, however, the conservative South that leads the way for “Merry Christmas” (the region is about evenly split), but the Midwest.

Age makes a difference too. Millennials are more likely than previous generations to see Christmas as a cultural rather than a religious holiday—a reversal of how older Americans feel. And a 2018 NPR/PBS Newshour/Marist poll found that 53 percent of Millennials prefer “Happy holidays,” versus 38 percent who like “Merry Christmas.” Although few good polls have delved into the views of Generation Z, these trends all point to a continued secularization in celebration and vagueness in greeting.

The big shift behind these changes is that even when all the faithful come, they are a shrinking group, and Christianity, in particular, is in steep decline. Robert P. Jones, PRRI’s president and founder, told me that the shift goes hand in hand with an increase in the number of Americans who identify as not religious. As a portion of the population, adherents to religions other than Christianity have barely increased over the past half century, but unaffiliated Americans are now a big share of the population even in historically very religious states. “Because of these shifts, younger adults who are religiously unaffiliated are also now much more likely to marry religiously unaffiliated partners,” Jones wrote in an email. “So the phenomenon of one partner bringing a religious celebration into the home happens less with the youngest generation.”

In 2021, as he left office, Trump declared he had triumphed against the war on Christmas: “When I started campaigning, I said, ‘You’re going to say “Merry Christmas” again.’ And now people are saying it.” But this seems like yet another premature victory celebration and another unfulfilled promise. If anything, the religious element of Christmas slipped in importance during Trump’s presidency, and like many of the cultural trends against which he railed, this one appears likely to continue into the future. In short, it’s beginning to look a lot like happy holidays, everywhere you go.