How do you pick up the reins to one of the most unique and auteurial horror franchises of all time? In 2007, British work-for-hire studio Climax found out the hard way, picking up the pieces of a misdirected Silent Hill prequel for the PSP before creating a memorable reimagining of the original game.

The Silent Hill series was in a strange place in 2005. The sales of each successive entry were worse than the last, and the esoteric vision of Team Silent, the internal Konami team behind the first four games, was at odds with the trend towards more guns-out horror. By the time Silent Hill 4: The Room came out, Konami Japan had all but given up on the series, and Team Silent was disbanded.

The Big Preview Horror Special hub has even more exclusive access to the biggest games in the genre on the horizon, and deep dives into iconic classics!

But over at Konami's US base, buzz around the upcoming Silent Hill movie and the reasonable success of a mishmash of videos, music and digital comics called The Silent Hill Experience on Sony's shiny new PSP suggested there may be some life yet in the moribund Maine town.

Around this time, long-running British studio Climax set up a Los Angeles office to tap into the lucrative West Coast games business. This move paid off, because by the end of 2005 it had penned a deal to make the next Silent Hill game – a prequel to the original Silent Hill designed for Sony's portable powerhouse.

This was great news for Climax, putting in its hands an original game in one of the great horror series. However, members of the studio's UK team, which was working on a Ghost Rider PSP game at the time, saw fundamental problems with the idea. Sam Barlow, writer and lead designer at the studio, spotted the red flags. "The very idea of making a prequel to Silent Hill wasn't good," he tells us. "That game told its story brilliantly through flashbacks, and there weren't really any unanswered questions."

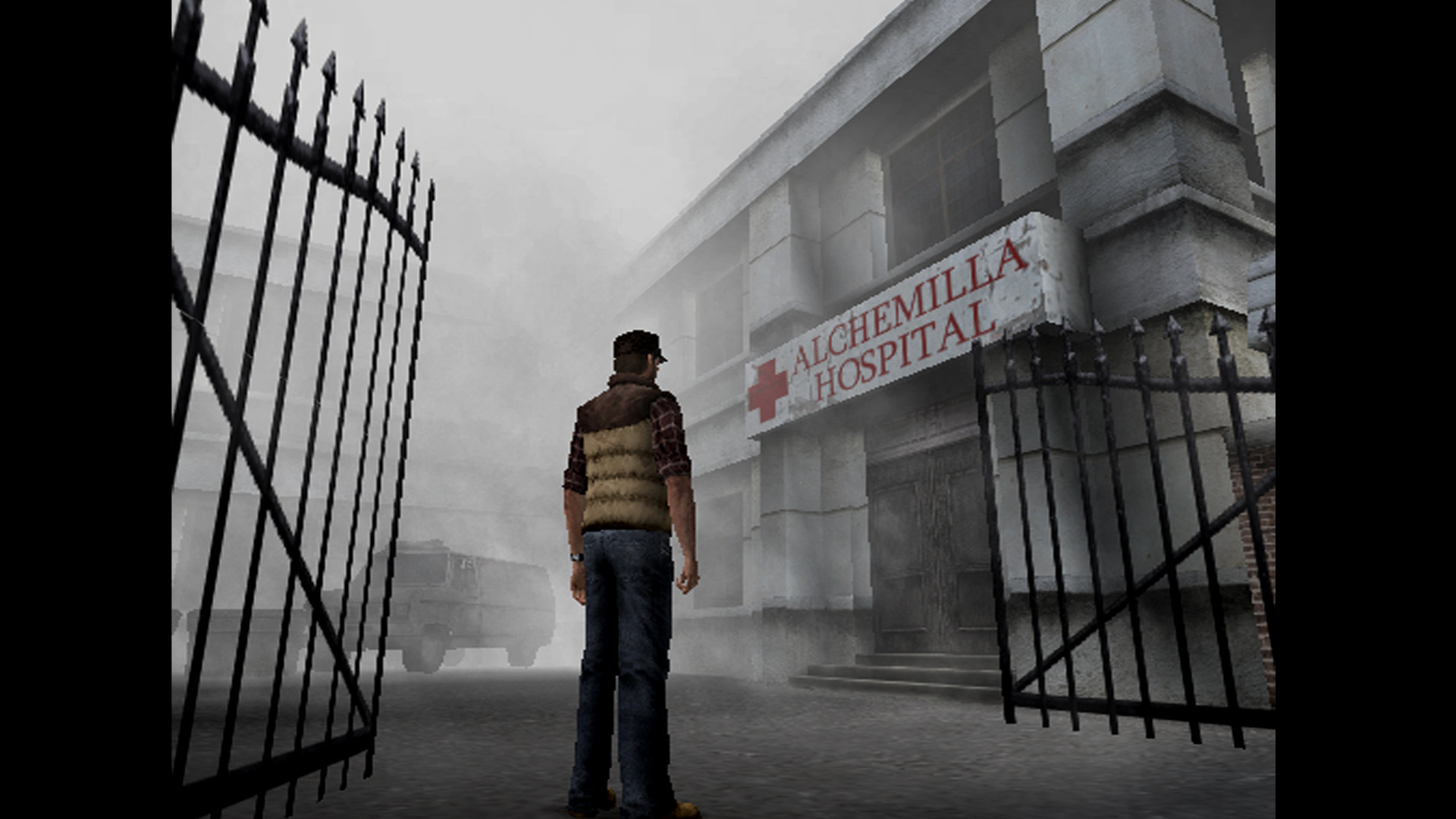

For several months, the UK team remained uninvolved as Silent Hill: Origins began forming into an action-oriented Resident Evil 4-style game, with an over-the-shoulder perspective that was never a comfortable fit for the PSP's stubby single analog stick, nor for the claustrophobic corridors so synonymous with Silent Hill.

The full extent of Origins' misdirection was revealed when the LA team came to the UK seeking help. Lead artist Neale Williams recalls the state of the game, "They built all these assets for the game on an engine that never appeared. They got to a stage in development where they were having to show something and just had some internal artwork."

This feature originally appeared in Retro Gamer magazine 214. For more in-depth features and interviews on classic games delivered to your door or digital device, subscribe to Retro Gamer or buy an issue!

The UK team mobilised quickly, building the armature for a Silent Hill game on the in-house engine it had built for Ghost Rider, while showing the LA team how to work with the tools. A demo existed within a couple of weeks and the LA team got back to work, but the gameplay footage shown at E3 2006 raised a lot of creative questions.

"People were saying the monsters looked like something out of Scooby-Doo. It didn't look great," Sam tells us. Beyond that, it didn't fit the existing lore or haunting tone of the series. Several characters were older in the prequel than in Silent Hill, while enigmatic psychiatrist Dr Kaufmann was suddenly an authority on the ghostly goings‑on when in the original game he was still trying to understand everything.

It was shaping up to be more Evil Dead than Jacob's Ladder (the key movie inspiration for the series). A less-informed studio could have let this tonal shift slide, but as it happened Climax UK was full of Silent Hill aficionados.

"At that point, we said to the heads at Climax that we could do a better job. Roughly half the time and money had been spent, the beginning and end cutscenes had been done, and Neale and I wanted to change everything," Sam recounts. "What was a demon bellhop doing in it?"

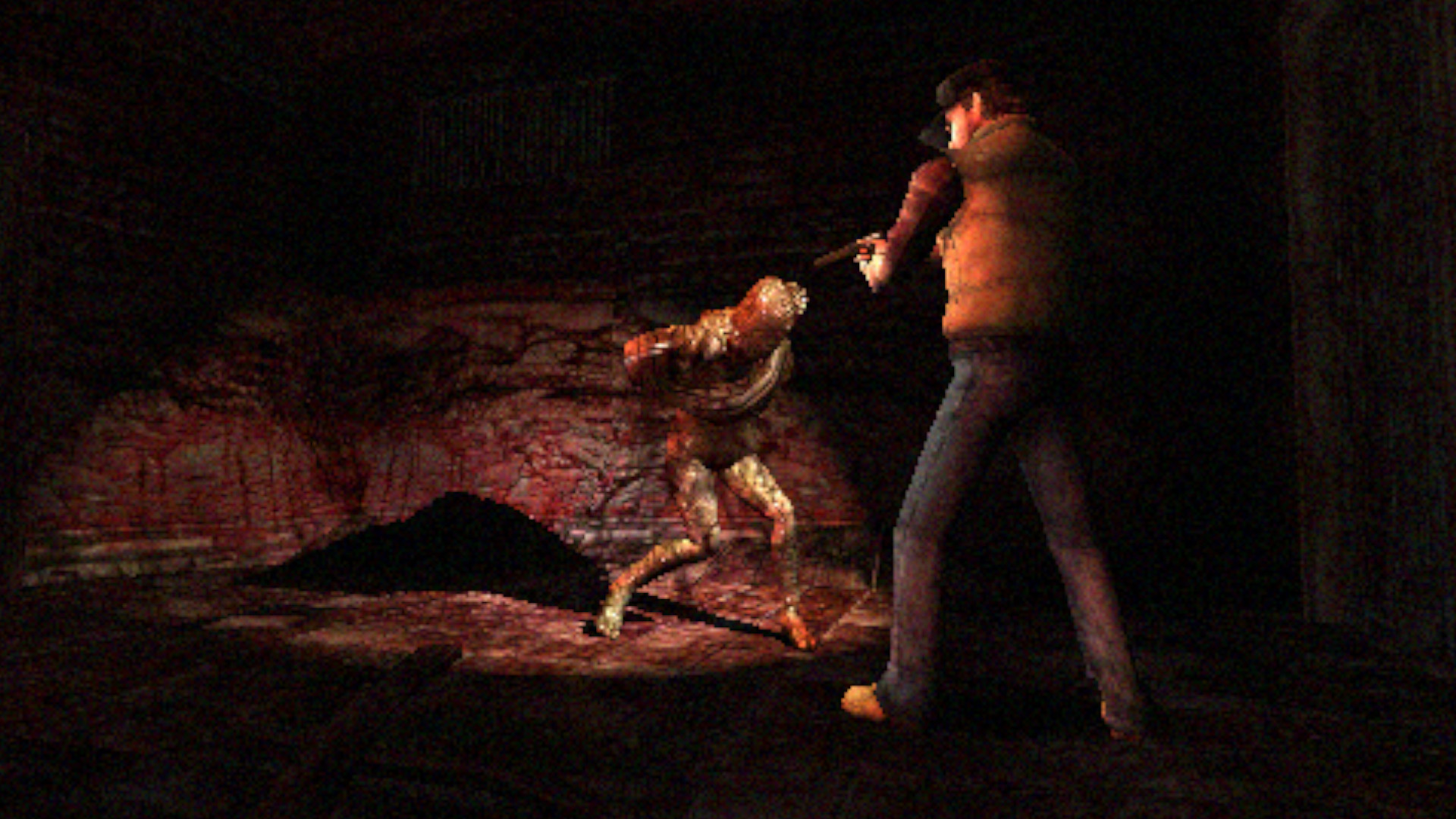

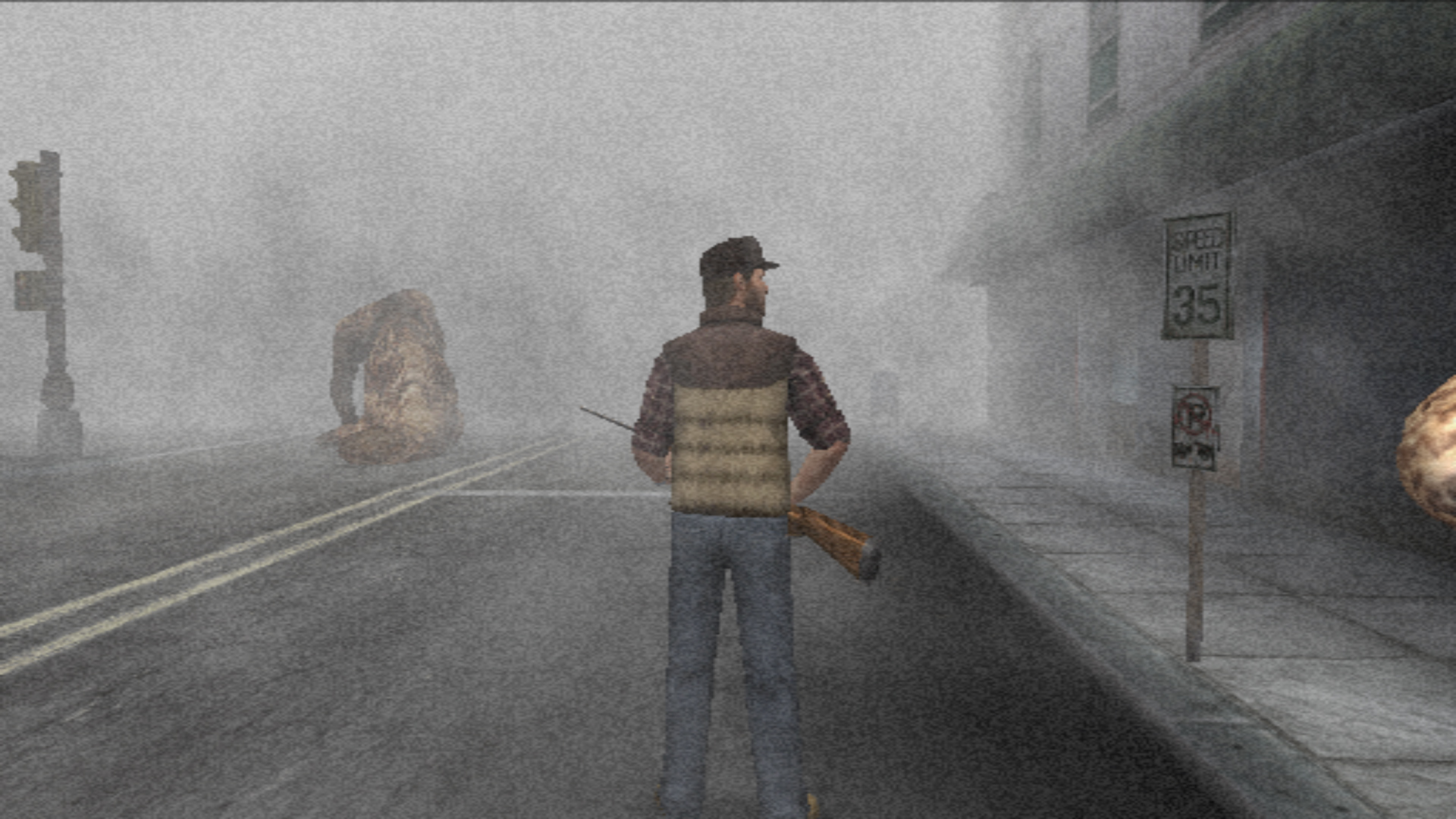

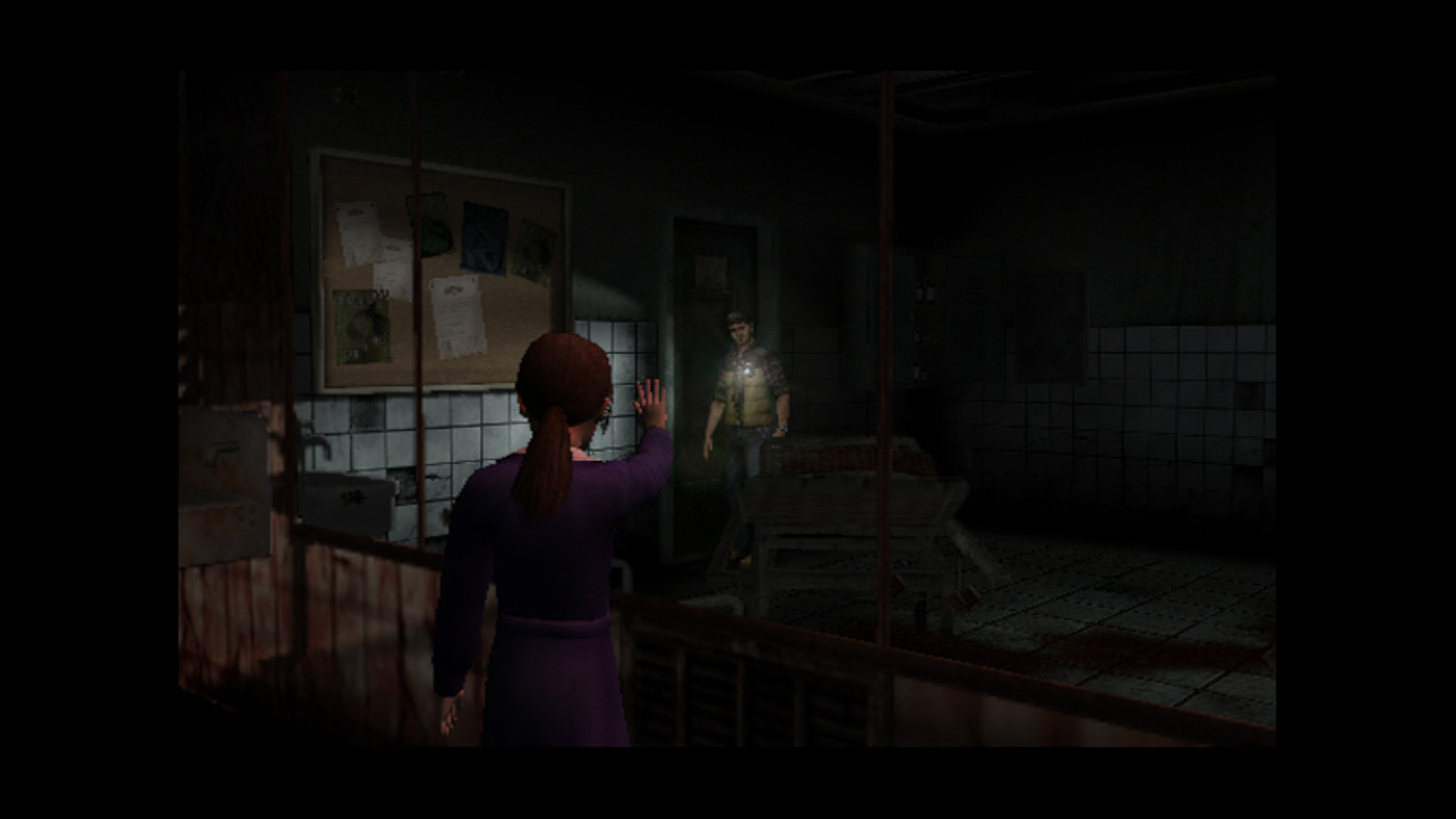

Sam and the team made their case, and in early 2007 a half-finished Silent Hill PSP game arrived at Climax HQ on the shores of Portsmouth. With six months until release, there was no time to completely reinvent the game, so the UK team looked back to the series' roots. The team defied the industry trend towards action horror by opting for semi‑fixed camera angles that recreated the intensity of the original game, while letting players switch to a regular third-person view with the press of a button.

Neale and Sam canned the Scooby-Doo creations, splitting the work of monster design between them. This led to some of the most menacing creatures in the series: the cow-like Carrion abominations, which drag themselves across the damp pavements due to their front legs being atrophied. Then there was the biggest creature in the series, Caliban, whose behooved legs bent over its head like a horrid hairy pretzel.

I thought it was cool and surreal, he thought otherwise (correctly).

Not every idea worked. There were many late nights at Climax, and Sam reveals one of the creatures he conceived during the graveyard hours. "Luckily, Neale was on hand to bring me round when I thought to have the hero Travis' dad represented by a leather chair with a spooky face," he recalls. "I thought it was cool and surreal, he thought otherwise (correctly)."

At Konami's insistence, the iconic nurses made a return, and the game features a Pyramid Head knock-off called The Butcher, who Climax UK had to keep due to his appearance in the marketing assets. "In Climax LA's version, The Butcher was the origin story of Pyramid Head, who was explained as 'a chef who went insane and attached metal to his head'," Sam tells us, while Neale laughs in recollection of the terrible idea.

Climax managed to get rid of the canon-killing backstory for the Butcher, but the character remained, limited to fleeting appearances and a surprisingly easy boss battle – his unceremonial demise perhaps payback from Climax UK for having to feature him in the first place.

Another point of contention was the hero Travis, a trucker with seemingly no connection to Silent Hill. Again, he stayed in the final product for marketing reasons, being the kind of butch hero that games were leaning towards at this time. "The best we could do was ground Travis a bit more, so that all locations had some link to his psychology," Neale reveals.

Throughout all this, Climax didn't have much input from Konami Japan. "This was a thorny PR question at the time because you didn't want to say you just made this stuff up as you went along," Sam admits.

Neale, however, does recall getting a hard drive with a dump of the Silent Hill 2 database on it. "Much of it was indecipherable, but there were also weird things like work trip photos," he recounts. "There was this weird voyeuristic experience of looking for textures of [Silent Hill 2 protagonist] James Sunderland only to find pictures of guys sitting in motel rooms in T-shirts and underpants drinking beer."

Climax's office was a bright space, which proved to be an unforeseen hindrance during development. "It was this lovely fishbowl studio where the walls were all made of glass and the sun was constantly shining through, while we were making a game predominantly set in the dark on these shiny little screens," says Neale. "We bought big blankets for the team to put over their shoulders when playtesting."

Silent Hill: Origins came out on the PSP in November 2007. While it didn't break new ground, it was precisely the solid Silent Hill throwback Climax intended to make. It maintained the series, leaning on the novelty of the PSP to deliver an atmospheric, old-school survival horror well outside the genre's heyday. Crucially, it showed Konami that Climax could be trusted with the Silent Hill IP.

To this day, Sam remains proud of the turnaround job the team did on the game. "If people were to ask me, 'What is the achievement you're most proud of in games?' Origins might be there just in terms of what the team turned out given those constraints".

Soon after Origins and the surprisingly successful movie, Konami approached Climax about a possible sequel. Climax boss Simon Gardner rejected the idea, believing there was little to be gained commercially or creatively from a follow-up. At this point, Konami producer William Oertel stepped in to offer Climax a sweetener: the option to create a Silent Hill remake for the Nintendo Wii, provided the studio made a PSP game too.

We made an effort to step back from the very blinkered take on horror that originated from Resident Evil.

Climax accepted, and were quickly beset by publisher demands: Konami wanted to emphasise Wiimote melee combat, William wanted a survival‑like system that involved scavenging heat-control pills. Climax wanted none of these things, hoping to instead shake up the genre by moving away from combat and violence towards something more subtle and congruous with the Silent Hill style. "We made an effort to step back from the very blinkered take on horror that originated from Resident Evil – the shotguns, crowbars, headshots and resource scavenging – to ask what a horror game should look like," Sam reveals.

While the foundations of Silent Hill are grounded in works like Jacob's Ladder and surrealism, Sam also looked to two less likely places for inspiration. "I thought of Battlestar Galactica, a reboot in which some characters had the same names but they reinvented everything," he says. "So I said, 'Why don't we do a reboot like that?' This idea of the psychiatrist interviewing the protagonist, the whole game can be a false remembering of something."

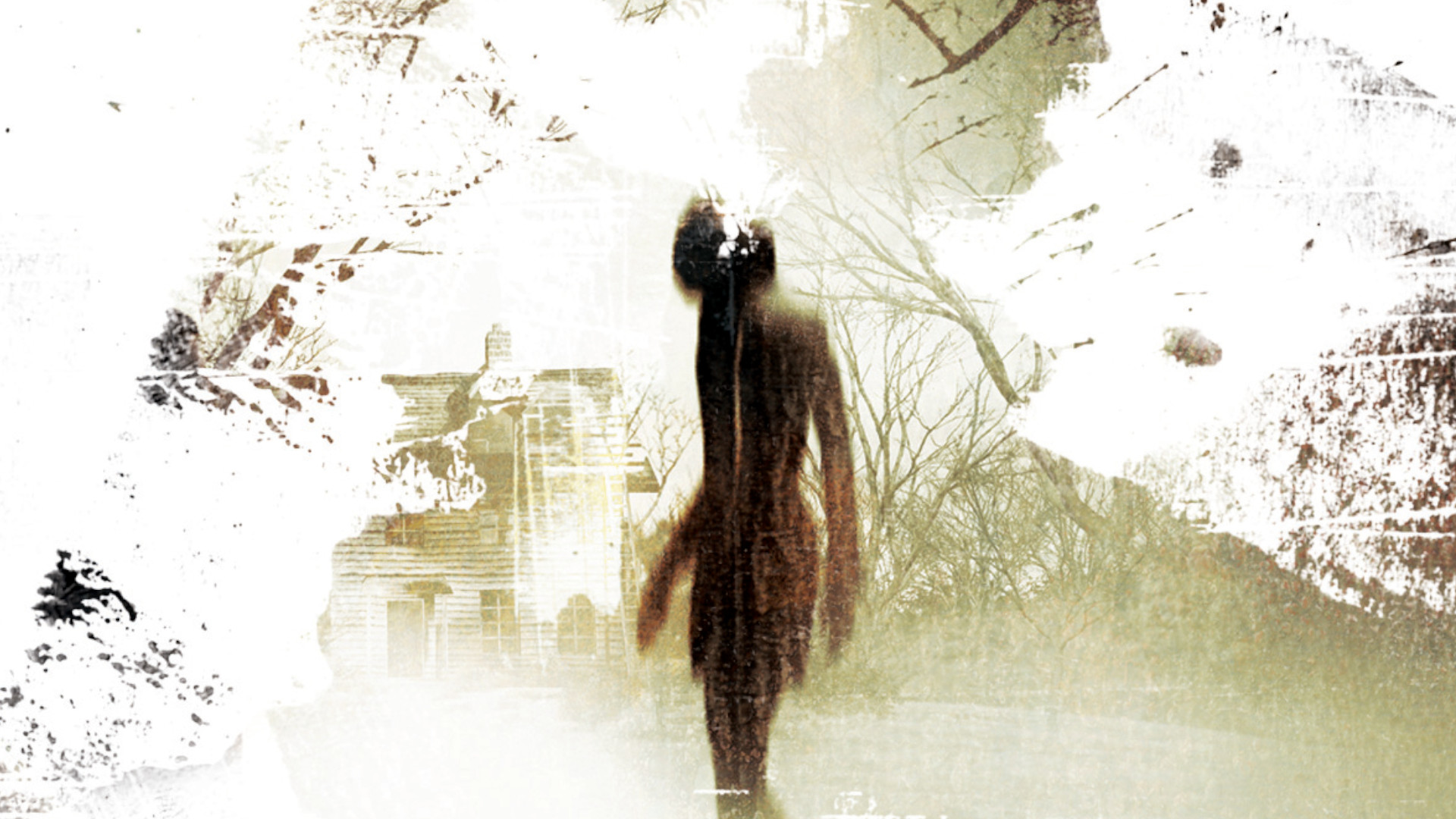

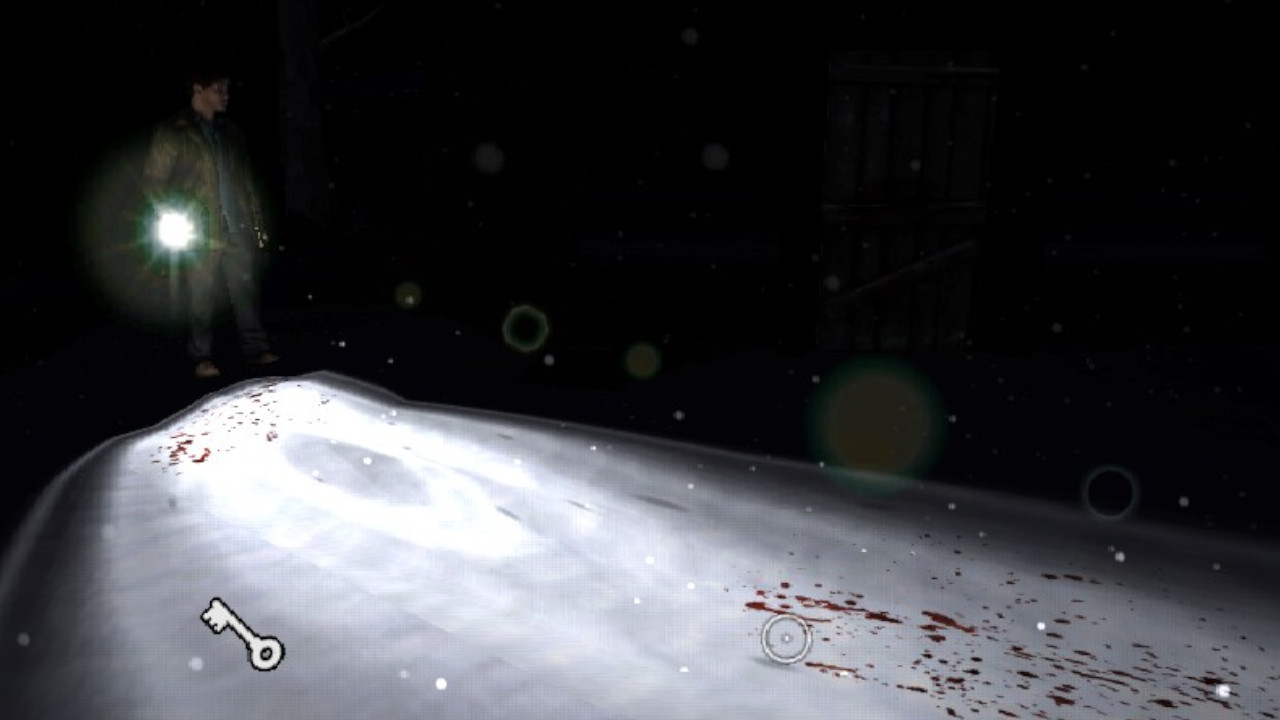

The premise of Shattered Memories was born. It would retell the Silent Hill story of Harry Mason searching for his daughter, Cheryl, following a car crash, but do away with the cult and paranormal activity to deliver a more intimate story. There would still be monsters, but they'd be confined exclusively to the now-frozen Otherworld – a place that, it would transpire, was a manifestation of Cheryl's psyche, not protagonist Harry's.

The second unlikely inspiration for Shattered Memories was the slasher horror subgenre. "Slasher movies have this wonderful structure which enables you to build up suspense, anticipation and dread," Sam elaborates. "You have the daytime sequence where no one gets killed – character-building, mystery, investigation – then night falls and suddenly someone is home alone. Now it becomes suspenseful. Then the bad guy jumps out for the fear, adrenaline and chase."

These ideas came together for an uncannily prescient game. In the light world, Shattered Memories was a combat-free walking simulator before the genre exploded with Dear Esther in 2012. It was eerily relaxing exploring the streets of Silent Hill without fear of attack, unfolding the narrative through environmental interactions like taking photos on your camera phone, and puzzles that cleverly utilised the Wii's motion controls. You could snoop through drawers, shake cans with the motion controls to see if objects rattled inside, and textures were clear enough that you could read signs and letters without text pop-ups taking over your screen.

But encounter a harrowing memory and the world would suddenly freeze over. The nocturnal Raw Shocks began stalking you, and you could do nothing but run or hide. Again, Shattered Memories anticipated a genre revolution before it began (this time the fight-or-flight horror popularised by Amnesia: The Dark Descent in 2010). Hiding in lockers and watching through the slats as fleshy, squealing creatures scurried by foreshadowed the locker-cowering of Alien: Isolation five years later.

Shattered Memories was an anomaly on every level.

With Isolation developer Creative Assembly's offices being under an hour's drive from Climax, Sam believes the connection might not have been coincidental. "If you make a game like Shattered Memories that's not necessarily a huge hit, on the Wii, it's the perfect game to take inspiration from – a cool game that wasn't played much," he suggests.

Shattered Memories was an anomaly on every level; on the Wii where it was surrounded by family-friendly games, in a horror genre that leaned into action, and even within the Silent Hill series itself, untethering it from the awkward combat that Sam and Neale felt was dissonant with its wider vision. The fact that in earlier games it became a widely accepted strategy to simply slalom around the enemies revealed the flaws of the system.

But to omit combat completely, Climax had to use a bit of cunning. Producer William Oertel was insistent that Konami wanted motion‑control combat, letting players physically flick at monsters with their Wiimotes. However, when William was fired late in development, Climax pounced on the one-day transition between producers to enact their vision.

"In one afternoon we took the design docs, removed all the bits we didn't like – the temperature pills, the combat – and uploaded the document the next day," Sam recalls. "The new producer turned up the next day and told us what we were doing was very ambitious. We just said, 'Yep, that's what's been signed off!'"

Shattered Memories' dichotomy between melancholy light world and vicious dark world was punctuated by Akira Yamaoka's score – the only contribution to the game by an original Team Silent member. While Climax was delighted with the work he did, limited communication led to some strange misunderstandings.

"At this point, he was very into vocal tracks. He had a guy in LA who would write the lyrics for the music," Sam remembers. "We sent him very specific briefs. The first track he sent back, the lyrics went something like, "Why did you have to die in that car crash daddy. I've been screwed up ever since.'" While Shattered Memories would contain more vocal tracks than previous games, the more on-the-nose ones were reeled in.

Through the team's focused creative vision, Climax made the game it wanted, while a separate PSP game was scrapped for budgetary reasons, replaced by a PSP port of Shattered Memories. But this was a Wii game by design, and possibly the most complete use of the console's technology – from answering phone calls and hearing the radio static of enemies through the Wiimote speaker, to taking photos and shaking off enemies by flailing the controllers. Not to mention the incredibly ambitious psychological profiling system (see boxout).

Konami demanded a PS2 port of Shattered Memories, which was never going to show the game in its best light. Nevertheless, it was aimed at South America where the PS2 was still popular, and proved to be a hit. "To this day, whenever I have conferences in South America I have people wanting me to sign their copies of Shattered Memories," Sam says.

The popular thinking is that the 'true' Silent Hill ended after Team Silent disbanded. But amongst the dodgy dungeon crawlers, Pachinko machines and other misguided takes on the series, Climax's efforts stand tall. Silent Hill is, after all, a subjective place – a setting where the tangible reality of a sombre East Coast town makes way for a nightmare of symbolism and interpretation. Climax understood where the series came from and returned there with Origins, only to then take Shattered Memories to a place where videogame horror hadn't quite gone before.

Check out our best Japanese horror games list if you want more chills!