Mitch McConnell isn’t known for his joyousness, but the dour Senate Republican leader was able to find delight even in the bleak aftermath of the January 6 insurrection: This, at long last, was the end of Donald Trump.

“I feel exhilarated by the fact that this fellow finally, totally discredited himself,” McConnell told the New York Times reporter Jonathan Martin late that night, according to Martin’s forthcoming book with Alex Burns, This Will Not Pass. “He put a gun to his head and pulled the trigger. Couldn’t have happened at a better time.”

Across the Capitol, House Republican Leader Kevin McCarthy also foresaw Trump’s demise. Unlike McConnell, McCarthy had worked hard to stay on Trump’s good side. Now, however, he’d had enough. “What he did is unacceptable. Nobody can defend that and nobody should defend it,” McCarthy told members of his leadership team four days later. He said that with impeachment sure to pass the House and conviction in the Senate a strong possibility, he would recommend to Trump that he resign, though he didn’t expect the president to take the advice.

[David A. Graham: Don’t let them pretend this didn’t happen]

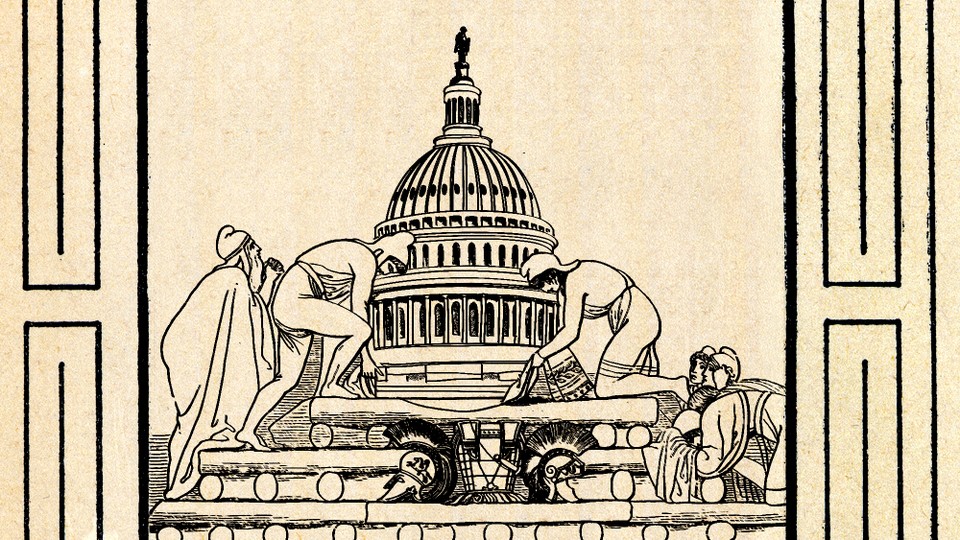

As a former House member once noted, a politician should never let a serious crisis go to waste. McCarthy and McConnell had a moment to finish off Trump, who had long bedeviled them personally and haunted the party. On January 7, they had the means to end his elected career once and for all, and they had the votes. But they flinched, throwing away the chance to help themselves, and perhaps even to save the republic. The story is a tragedy of the Congress, a failure of collective action leading to ruin.

What is remarkable about the reporting in This Will Not Pass, and especially in leaked recordings of McCarthy, is the unvarnished picture it gives of GOP congressional leaders’ views about Trump and about the MAGA faction in the House. Throughout the Trump years, Republican members lived in fear of the president and toed his line in Congress, but would moan and groan about him anonymously. You can call this cowardice—I have—or you can chalk it up to a warped pragmatism. These elected officials rationalized their submissiveness by saying they could help contain Trump, keep the MAGA hordes at bay, and be ready in case of a crisis.

The tension between McConnell and Trump was never a secret. The Senate stymied the president from time to time, and Trump would rail against McConnell, but the men were brought together by a shared desire to confirm conservative judges and hurt the Democratic Party. McCarthy worked harder to remain publicly in step with Trump.

Privately, many GOP leaders hated Trump, as exemplified by McConnell’s exhilaration. Some of their disdain was a revulsion at his law- and norm-busting; some was a loathing of his politics, never fully aligned with traditional D.C. conservatism; some was anger about how he had warped the functioning of Congress, and thus made their own lives difficult. They disliked the members most closely aligned with him too.

In leaked recordings, McCarthy wondered whether Twitter could ban some of the most extreme members of the caucus, just as it had banned Trump. On a January 10 call, leaders expressed horror that several members had spoken at Trump’s rally on January 6. McCarthy called Representative Mo Brooks’s comments that day (“Today is the day American patriots start taking down names and kicking ass”) worse than Trump’s, and he fumed about how Representative Matt Gaetz’s were dangerous—not to the health of American government, but to the lives of members of the House. “He’s putting people in jeopardy,” McCarthy said. House Republican Whip Steve Scalise, publicly a close ally of Trump’s, went further: “It’s potentially illegal what he’s doing.” All in all, the discussion on the tapes shows that behind closed doors, nothing Republican leaders were saying would have been out of place on CNN, or perhaps even on MSNBC.

For a few days following the riot, McConnell and McCarthy had the chance to rid themselves of Trump. The former president wouldn’t have disappeared from the scene, and he would have retained a powerful voice and influence to dog them. But they also could have ensured that he was blocked from the presidency, closing off his electoral career. If Republicans had rationalized their earlier acquiescence on the premise that they might someday need to stop Trump, this was the moment they were waiting for.

They almost certainly had the votes. McCarthy was never going to get a GOP majority to vote for impeachment—some of his members loved Trump, and many others were still too cowed by Trump—but he knew that Democrats would impeach Trump anyway, and a conviction would have freed the fearful Republicans. On the Senate side, conviction required 67 votes, and Democrats were likely to provide 50 of them. Getting a Republican majority seemed tough, but getting to 67 would be no problem as long as the powerful McConnell voted for it and pushed other Republicans to do so. Meanwhile, polls in the days after the insurrection showed that the public was furious and blamed Trump.

Then Republican leaders froze up. Exactly when this happened remains unclear, but the shift was complete by January 13, one week after the riot. That day, the House voted to impeach Trump. But McCarthy had already gone weak. He did not whip his caucus to vote yes, and he voted no. In the end, only 10 Republicans voted in favor. That day, McConnell rejected calls for a quick impeachment, saying that because Trump was leaving office anyway, the matter could wait until Joe Biden was inaugurated.

[David A. Graham: The end of the Republicans’ big tent]

The most charitable interpretation is that McCarthy and McConnell got greedy: They hoped Democrats would do the dirty work of getting rid of Trump for them, saving them from having to take the political hits. “I didn’t get to be leader by voting with five people in the conference,” McConnell told a friend, according to the authors of This Will Not Pass. He seemed convinced that Trump had self-destructed, without accounting for the need to nudge the process along.

But with each day that passed, the MAGA crowd was able to talk people out of what they had just seen, to create excuses, to sow doubt. McCarthy and McConnell were surely keeping abreast of conservative media, where an effort to excuse the insurrection took hold quickly. They must also have been haunted by the memory of the October 2016 Access Hollywood episode, in which a recording was leaked of Trump boasting about sexually assaulting women. For a moment, Republicans seemed ready to throw Trump over, but the nominee managed to hang on, and then went on to win the presidency. His survival made Republicans gun-shy.

The delay was fatal. By the end of January, it was too late. When the Senate finally voted in February, seven Republicans voted for impeachment. Other gettable votes had probably been spooked by the House vote. McConnell himself voted no, even as he scorchingly condemned Trump in a floor speech. Within months, Representative Liz Cheney, one of the participants on McCarthy’s calls, was stripped of her leadership position for saying in public some of the same things McCarthy had said privately.

The failure to punish Trump is bad for the United States. But although it’s tempting to say that McCarthy and McConnell sold out the greater good for their own gain, they may not have even gotten that. McConnell could become Senate leader again next year, but he’s endured months of attacks from Trump, and the former president’s influence will make it even harder for him to run the chamber. McCarthy might have it worse. The leaked recordings have stirred up opposition to him, especially among the members he complained about in January 2021. Trump seems prepared to forgive, at least for now, but Tucker Carlson—the other leading light of contemporary conservatism—has launched a crusade against the House minority leader. McCarthy could become speaker, but he’d start the job weaker than his two Republican predecessors, who were both run off by their caucuses.

McCarthy and McConnell aren’t the only potential victims of their failure of nerve. So are Congress’s power to check the executive branch, the rule of law, and the Constitution itself. Their failure of collective action has become ours.