Consider it either a referendum on the school’s vitality and popularity … or on its meager state funding and therefore dorm space. But, Lord almighty, does Indiana University come dense with off-campus housing. So much so that, charming as it is, Bloomington, Ind., can present less as a Midwest college town than as a collection of apartments, townhouses and villas, with a major state university tacked on.

Having realized years ago that there was—and is—a fortune to be made as a developer catering to students, Scott May is among the largest real estate holders in town, the baron of thousands of rentable apartment units. Which is ironic because there was a time when May’s dalliance with Bloomington apartment living imperiled one of the signature events in IU history: the 1975–76 Hoosiers’ perfect 32–0 basketball season, the last time a Division I men’s college team went baseline to baseline without losing a game.

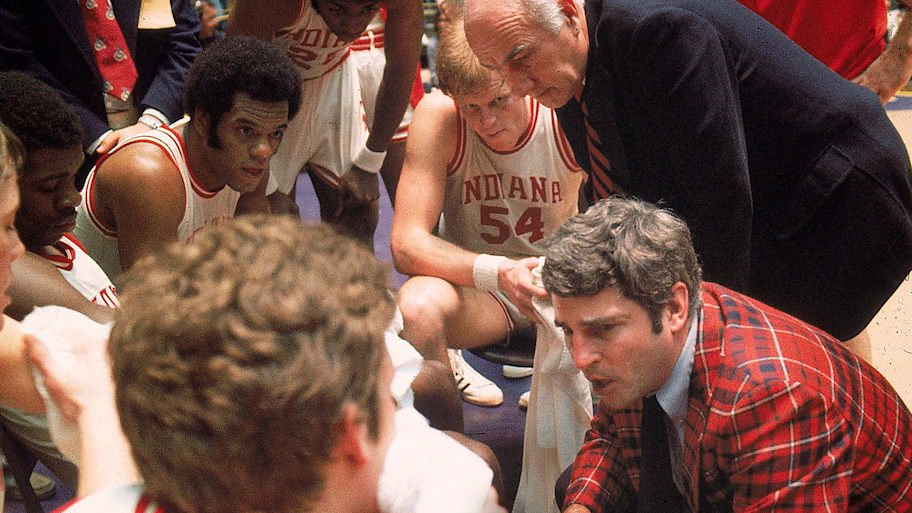

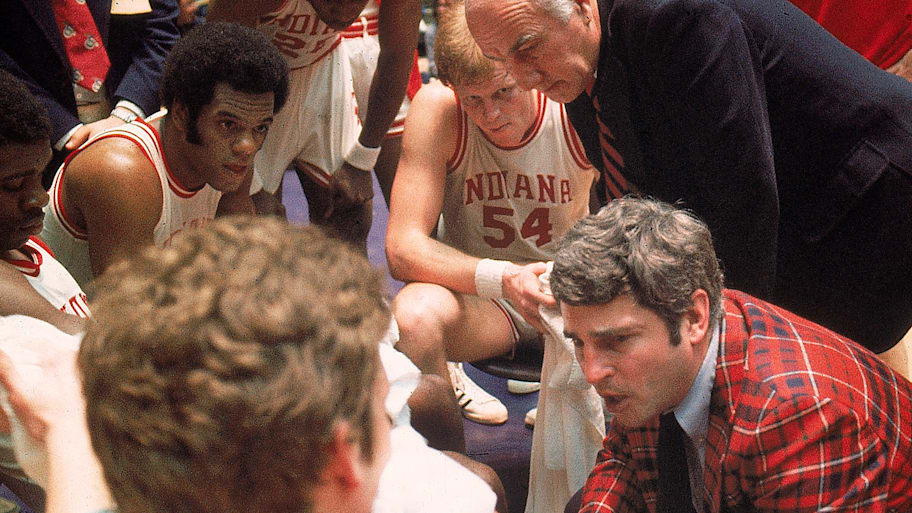

But in the fall of 1975—an even 50 years ago—May and fellow Indiana senior Quinn Buckner made the unilateral decision to leave the dorms and move off campus. Unilateral in the sense that they did not first confer with their team’s head coach. When Bob Knight found out about this relocation plan, he was, in keeping with his default emotion, livid.

Knight blasted the players for their selfishness, for the bad habits that, surely, would befall 21-year-olds leaving the college environment to live on their own. As Buckner once recalled to Sports Illustrated: “He told us we weren’t sleeping right and eating right. And you know what? He was right. We moved back into the dorm.”

A few months after that—well-rested, well-nourished and well-integrated into the campus at large—May and Buckner, team co-captains, were on the floor at the Spectrum in Philadelphia when Indiana closed out its perfect season. The players felt exultant. And relieved. And vindicated, having righted the injustice of the previous season.

The idea that a pair of seniors moving out of dorms into (horrors!) an off-campus apartment would arouse their coach’s wrath? Today, of course, it scans as downright quaint. But consider the historical sports context. This was the mid-70s, a time when Nike was just an upstart company with a name from Greek mythology; ESPN had yet to be founded; and NIL would have been recognized only as a possible score in an overseas soccer match.

This was still a time when it was considered a fair exchange for varsity athletes to be given scholarships and textbooks in return for providing sports services. The idea that a player would leave college before four seasons of eligibility and enter the NBA was perceived as an act of fierce disloyalty. It was similarly unthinkable that schools would scour the country—never mind the world—recruiting talent; Indiana’s entire roster of players that gilded season came from within the state or a bordering one.

“We were bred a little differently,” says Bob Wilkerson, also a senior starter on the ’75–76 team. “We knew it would be four years that we would be there. For me, I didn’t realize I would be in the army, but, hell, I learned quickly. You do what you’re told and you try to learn, but you never think about quitting.”

Players dressed down for living off campus? Staying at school for four years? Made to feel like soldiers at boot camp, yet rarely even considering transferring? Stories like this encapsulate just how much time has elapsed since the last Division I men’s hoops team turned in an undefeated season, and just how much the balance of power today has shifted toward the athletes. They also go a long way toward explaining why no team has since replicated the Hoosiers’ feat.

The title itself came in 1976. But the propulsive thrust of the story behind the last undefeated team in D-I men’s basketball history comes from the year before. Heading into the 1975 tournament, Indiana was the consensus favorite, having blitzed through the season with a 29–0 record. But in the final game of the Big Ten season, May, Indiana’s best player, broke his left arm.

Indiana played Kentucky in the Elite Eight in Dayton, Ohio, an easy drive from both Bloomington and Lexington. Recent history added to the intensity. The Hoosiers had not only humiliated the Wildcats, 98–74, when they’d played earlier that season, but before that game, Indiana’s impulsecontrol-challenged coach had slapped his Kentucky counterpart, Joe B. Hall, on the back of the head, and then declined to offer a full apology. (“If it was meant to be malicious,” Knight said afterward, “I’d have blasted him into the seats.”)

Facing a fully motivated opponent and with the team’s best player consigned to a cast and playing only seven minutes, Indiana lost 92–90. The Hoosiers would end their season in a funereal locker room, only the players’ sobs piercing the quiet. Until his death in November 2023, Knight would refer to this team as the best he’d ever coached.

Though May and, likely, redheaded sophomore center Kent Benson, would have been the equivalent of NBA lottery picks in 1975, neither considered leaving school. Instead, they and the other starters returned to Bloomington hellbent on another run at the title.

From their candy-cane warmups to the overwhelming smell of popcorn inside the home arena—the prosaically named Assembly Hall—there was something decidedly throwback about the 1975–76 Indiana Hoosiers.

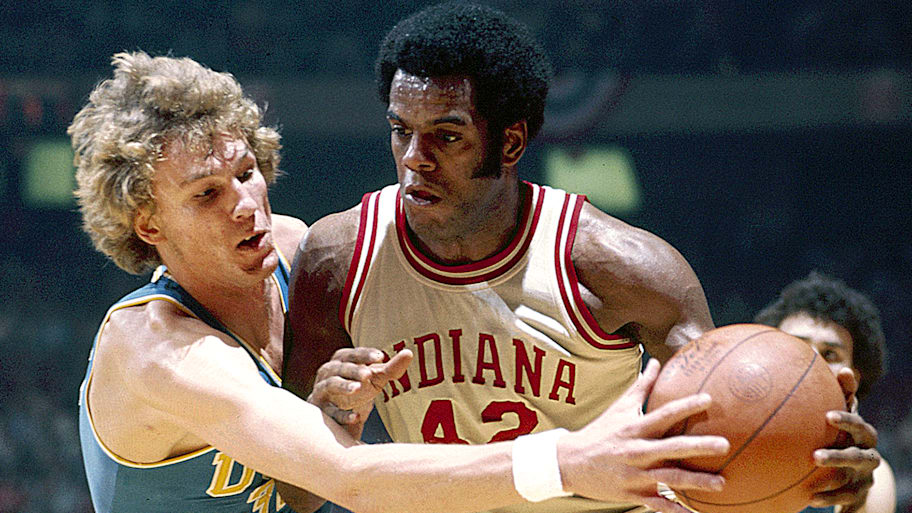

Above all, this was a classic example of a team greater than its component parts. They played a man-to-man defense in which each player was expected to help others when his man was off the ball. They passed up good shots for wide-open ones. With no three-point line, they put a premium on open lanes and easy looks in the low post.

It’s not that there weren’t fine players on the roster. All five starters would make it to the NBA. But there was strength in the unity, that sixth sense for knowing where the others would be on the court at all times. And while most teams say they are, this was one that was genuinely indifferent to who scored how many points, provided the team won.

Buckner could—and sometimes did—put up 20 points in a game; other times he’d direct the offense and barely score. Benson, an All-American, may have been the country’s best center but often went an entire game without attempting 10 shots. Wilkerson, a wildly versatile swingman, could—and did—grab 19 rebounds in a single game. Other times, he’d defend the opposing point guard on the perimeter. Even today, the players—now in their early 70s—reflect on the season by first referencing the team bonds, eager to deflect praise in the direction of a teammate.

(Digression: In reporting this story, I reached out to Benson and left a message on his voicemail. Within half an hour, he not only called back, but did so with Wilkerson patched in, happy to speak but on the condition that teammates from 50 years ago would also have their voices included.)

Inasmuch as there was a star attraction—and a source of tension—it was the team’s coach. Shortly before the season began, Bob Knight had celebrated his 35th birthday. In 1971, the same year Assembly Hall opened, Indiana had hired Knight from West Point—where he’d been named Army’s head coach at the preposterous age of 24. So by 1975–76, he was already in his fifth season in Bloomington and had already taken a team to the Final Four. What’s more, his reputation both as a singular hard-ass and singular basketball savant already had spread nationally.

When addressing the players, Knight was as likely to reference George Patton or Douglas MacArthur—his military heroes—as he was Pete Newell or Clair Bee, his basketball heroes.

Even in his mid-30s, Knight, clad in a red plaid sport coat, cut an outsized figure, equally demigod and demagogue. Still, for all the ink spilled about him, you find no references to his mulling competing job offers from deeperpocketed schools or NBA franchises. “People talked about whether he would be the U.S. Olympic coach [which Knight was in 1984],” longtime Bloomington sports journalist Bob Hammel recalled to me, not long before his death this summer at age 88. “But even the most successful coaches weren’t looking for better job offers and other schools weren’t looking to [poach] them.”

With that built-in stability, Knight was able to recruit the kind of players he wanted and felt he could nurture and nourish over four years. And the players could commit, secure in the assumption that there would be no convulsive change in coach or culture. “In other words, you knew what you were signing up for,” Buckner, one of Knight’s first recruits, once told me. “But it also meant everyone kind of grew up together.”

A few days after the 1975 loss to Kentucky, Knight received a handwritten letter from Bee, a pioneer of the game at LIU-Brooklyn who had become a mentor to Knight early in his career. From his home in Monticello, N.Y., Bee wrote in part: “Take a deep breath. Get your bearings. Set your sights on even greater heights and start all over again.”

Knight took this to heart, challenging his team not just to avenge the defeat by winning the national title, but to become the seventh team in NCAA history—the previous four were from UCLA—to turn in a perfect season.

Says Benson: “It wasn’t like we woke up in the middle of the season and were like, We’re 15–0! Wow, maybe we can keep this up. No, [going undefeated] was a goal from the start.”

The 1975–76 Hoosiers do not stand accused of padding the preconference schedule with cupcake games. The consensus preseason No. 1 team, Indiana started its campaign with a game against the Soviet national squad, which controversially had won gold at the 1972 Olympics. Technically it was an exhibition game, but it came freighted with real significance. The game was held at Market Square Arena in downtown Indianapolis and played before a sellout crowd of 17,377. (The Pacers, the venue’s full-time tenants, would draw an average of 5,556 fans that season.) Despite playing against men who were in some cases a decade their seniors, Indiana won 94–78.

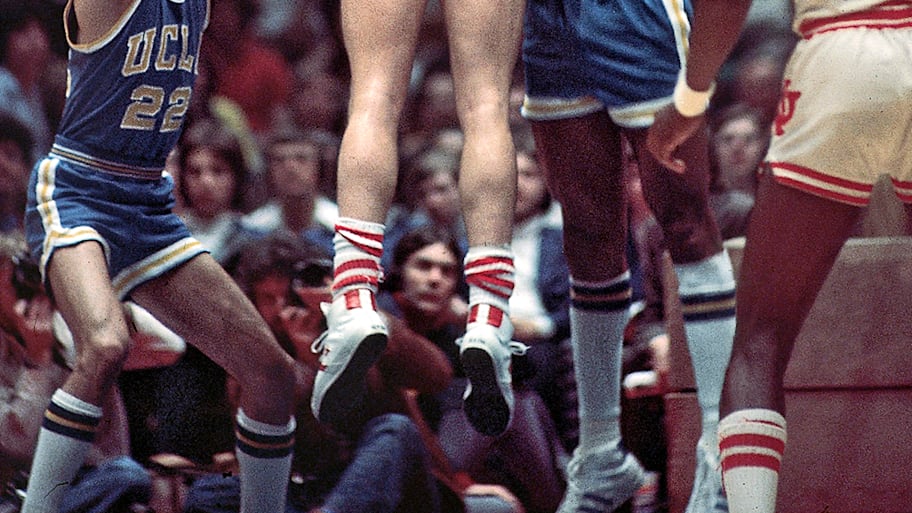

In the first regular-season game, Indiana faced No. 2 UCLA, the defending NCAA champions. This marked the Bruins’ first game since the retirement of John Wooden, and this clash of basketball superpowers was held in St. Louis. Broadcast on NBC, the matchup marked the first made-fornational-television college hoops game in history. Clearly the best player on the court, May scored 33 points and Indiana rolled 84–64.

Indiana then headed back to Market Square Arena to face Florida State. The Seminoles’ coach, Hugh Durham, offered this pregame gem: “They beat Russia to prove they’re the best in the world. And they beat UCLA to prove they’re the best in the United States. Now I’d like to see them prove they’re human and have a bad game.” No such luck. Indiana won 83–59.

Next up: eighth-ranked Notre Dame at home, a game the Hoosiers didn’t so much win as they stole, 63–60. Four days later, an appointment in Louisville with Kentucky. Though it was a wholly different Wildcats team, Indiana viewed this as a rematch of the heartbreaking Elite Eight matchup from the previous season. “No way we were losing that,” says senior forward Tom Abernethy. And they didn’t. It was a choppy game, but Benson slapped a missed shot into the hoop at the end of regulation to force overtime. Then Indiana pulled away, winning 77–68.

The Hoosiers started conference play without a Big Ten loss since March of 1974. They kept the streak alive, winning a tight game at Ohio State, 66–64, Knight matching up against his college coach, Fred Taylor. A week later, IU summoned its best moments when the situation required it, escaping with an 80–74 win at Michigan, generally regarded as the conference’s second-best team.

The return engagement with the Wolverines in Bloomington proved to be the season’s closest call. From the start, the Hoosiers were as flat as, well, Indiana, missing scads of shots and discomfited by Michigan’s pressure. At one point, backup point guard Jim Wisman committed turnovers on two straight possessions. Knight yanked him—first from the game and then, literally, tugging the player’s jersey almost to the point of ripping it.

With barely half a minute left in the game, the Wolverines led 60–56. Buckner’s only field goal of the game trimmed the lead to 60–58. Michigan missed the front end of a one-and-one, May grabbed the rebound and IU called timeout with 10 seconds to go. With no shot clock, it was obvious that Indiana’s best plan of attack was to hold the ball and give May the final shot. But when he was heavily defended, the ball ended up with Buckner, who fired and missed. Reserve guard Jim Crews retrieved the shot and flung it toward the basketball. Somehow Benson tapped the ball and sent it through the net as the buzzer sounded.

In 1976, a shot was good if it left a player’s hands before the buzzer. A tip-in counted only if it was already in the basket when the buzzer sounded. The officials huddled and ruled that Benson’s shot was a “shot,” much to the dismay of Michigan coach Johnny Orr. Indiana then pulled away in overtime and won 72–67. Such is the margin between heartbreak and history.

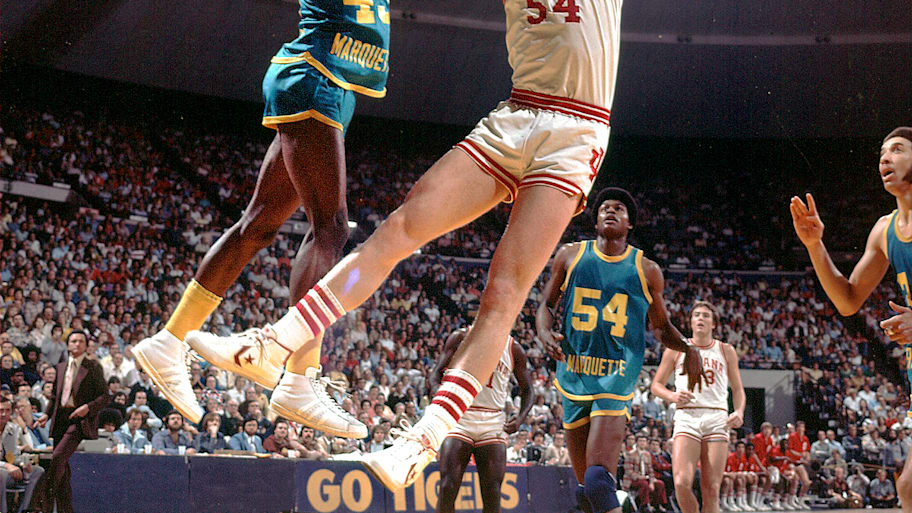

Indiana headed to the postseason as the team to beat. The previous season, the NCAA had expanded its field from 25 to 32 teams, which meant that multiple schools from the same conference could make the field. But teams were divided by geography, not seeding. So No. 1 Indiana was placed in the Mideast region alongside No. 6 Alabama and No. 2 Marquette, whom the Hoosiers would have to beat in succession.

The 1976 Final Four was held in Philadelphia, a fitting site in the country’s bicentennial. In the Final Four, Indiana had a rematch against UCLA. Before the game, the Hoosiers were taken aback by the braying of Bruins forward Richard Washington, who referred to Indiana’s December win as “a fluke.” This was precisely the kind of trash talk Knight would never abide. Indiana swarmed Washington, holding him to 15 points, and won handily 65–51.

The title game pitted Indiana against Michigan for the third time that season. Recent history fired the Hoosiers with confidence, secure as they were in the knowledge they had already beaten the team twice in the past few months. It also brought some trepidation; here was an opponent intimately familiar with their strengths and weaknesses. “No secrets between us,” says Benson.

In the pregame meeting, Knight’s college teammate John Havlicek, then nearing the end of his Hall of Fame NBA career, addressed the team. His message: You don’t want to look back. You don’t want to regret the rebound you should have grabbed or the loose ball you didn’t pursue with sufficient effort. Lay it all on the line tonight so you don’t live with any regrets in the future.

The game started inauspiciously for the Hoosiers. Less than three minutes in, Michigan’s Wayman Britt went for a layup, Wilkerson trailing in pursuit. Britt inadvertently raked his elbow across the left temple of Wilkerson, who fell to floor. Concussed, he was taken off on a stretcher and transported to Temple University Hospital, where he demanded to remain in his jersey and sweats, in case he might be summoned for the second half.

Owing to some combination of shock at seeing a teammate stretchered off, the weight of the moment and hot shooting by Michigan (60%), Indiana trailed 35–29 at halftime. Players recall that it all seemed unfair. Their season, undented so far, was going to be ruined on the very last night? By a team that Indiana had already beaten twice? With another fluke injury? In the locker room, Knight’s halftime speech was a single sentence: “If you guys want to be champions and make history, you’ve got 20 minutes to prove it.”

They did and they did. Playing to seize the title—not merely win it—Indiana, as SI writer Barry McDermott described it, played “with a flourish as conspicuous as John Hancock’s signature.” Turning in one of their strongest halves of the season, the Hoosiers didn’t merely take the lead but expanded it to double figures.

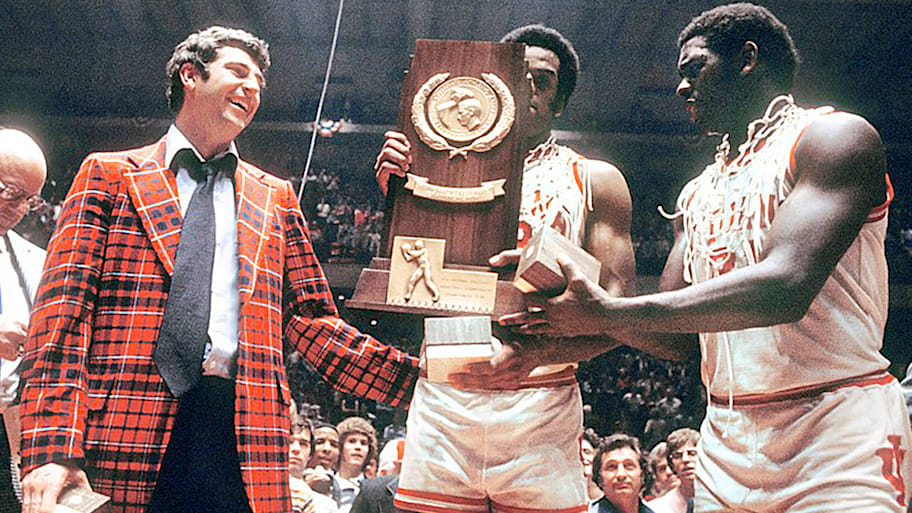

Wilkerson’s replacement, Wisman—the same player whose jersey Knight had grabbed the last time Indiana faced Michigan—played his best game of the season. May ended up with 26 points. Benson was good for 25 and took the Final Four Most Outstanding Player award. The final score, 86–68, punctuated a season of dominance. In the locker room, players wore scraps of net as necklaces.

“I feel so good,” May, the consensus national player of the year, said at the time. “I can’t even talk.”

“Four beautiful years and it paid off with this,” Buckner interjected. “Beautiful.”

Outside the Spectrum, Hammel ran into Knight.

“Congratulations,” said the journalist.

“Thanks, but it should have been two,” Knight said, referencing the 1975 disappointment.

Then Knight and Havlicek headed off into the Philadelphia night. Not to a media appearance or some Broad Street watering hole or a private jet waiting. No, they went to the hospital to check on Wilkerson.

There are all sorts of ways to express 50 years as a function of time. Consider that more than 70% of the current U.S. population had not yet been born when Indiana won that title. The U.S. GNP in 1976 was $1.9 trillion. This year it will be roughly $30 trillion.

Framed in sports terms, in the last half century, there have been:

- Fifteen perfect games and seven unassisted triple plays in Major League Baseball.

- Four horses that have won racing’s Triple Crown.

- Nine tennis players who have completed a career Grand Slam.

In March 1976, Gerald Ford was president, Muhammad Ali was still heavyweight champion, Tiger Woods was three months old.

Since 1976, five Division I men’s college basketball teams have gone through the regular season undefeated. Ironically, the next to do so was Indiana State in 1979, led by Larry Bird, who had transferred from Indiana. The Sycamores, though, lost in the ’79 final to Magic Johnson and Michigan State. Most recently, in 2021, Gonzaga was 31–0 heading into the title game before losing decisively to Baylor.

At the 1976 Olympics in Montreal, May and Buckner were starters on the U.S. basketball team that won back the gold medal. May (No. 2), Buckner (No. 7), and Wilkerson (No. 11) were early selections in the NBA draft. A year later Benson was the No. 1 pick.

It’s telling that all five starters still live in Indiana, most with deep ties to Bloomington. May is a local developer. Benson lives in his hometown of New Castle and is a regular at IU basketball games and volleyball matches, as his daughter Ashley was an All-American for the Hoosiers in 2009. Buckner is president of the IU Board of Trustees. He is also VP of communications and a television analyst for the Pacers. Abernethy founded the Indiana Basketball Academy in Carmel. Wilkerson recently moved back to his hometown of Anderson, just under 100 miles from Bloomington.

On the continuum between records-are-made-to-be-broke indifference and 1972 Miami Dolphins arrogance, the Hoosiers have, with age, inched toward the latter.

“I don’t think it’s gonna happen again, at least not in our lifetime, so yeah, we take a lot of pride in it,” says Wilkerson. Adds Benson: “There were [undefeated teams] before us, so maybe it wasn’t that big a deal at first. But since we’re talking 50 years now, yeah, it’s a big source of pride, especially for all the IU fans.”

The legacy has been made a bit more complicated— and more urgent—on account of the coach. Knight would guide Indiana to another national title five years later; and then another, six years after that. He would remain in Bloomington for 24 more years—too long, he would later concede—leaving after an ugly, public divorce.

The members of the 1976 title team remain fiercely loyal to their coach and seem to be in agreement that if his methods wouldn’t fly today, well, the current culture is the worse for it. But players on other Indiana teams have been more critical and, nearly a quarter century after Knight’s last game, the fabric of the Indiana basketball tapestry remains somewhat tattered.

To commemorate the golden anniversary of the undefeated team, the players have planned a series of events, speaking tours and media appearances. It’s as much to celebrate a milestone as it is to rekindle the good vibes from a less complicated time, when Hoosier basketball was top in class and college sports were pure as Indiana corn.

Whether it was the season’s last bit of master psychology or simply his devotion to the job, after the 1976 final, Knight did not fly back to Indiana with his players. He left Philadelphia immediately to scout potential recruits at a national high school all-star game.

But he met up with the team a few days later at a celebration at Assembly Hall. Clogging the state roads that thread together Indiana’s small towns, thousands of fans had taken off from work and school to toast the undefeated team.

Dressed in street clothes, players took turns at the mic, offering thanks and cracking lighthearted jokes. When it was Knight’s turn to speak, he kept his remarks short. “Take a look at this group one last time,” he told the adoring crowd, “Because you’re not gonna see a group like this again.”

More College Basketball from Sports Illustrated

Listen to SI’s new college sports podcast, Others Receiving Votes, below or on Apple and Spotify. Watch the show on SI’s YouTube channel.

This article was originally published on www.si.com as The Real Reason the 1976 Hoosiers Are Still College Basketball’s Last Perfect Team.