Purdue Pharma recently reached a $7.4 billion settlement with all 50 states and the District of Columbia over its alleged role in fueling the opioid crisis through aggressive marketing of OxyContin. Regardless of the case's merits, this landmark deal highlights what can happen when an expedient narrative replaces data-driven public policy.

Nowhere is the gap between narrative and data more clear than in West Virginia, the hardest-hit state in the country. While a wave of books and Netflix docudramas has promoted an oversimplified and often misleading storyline, new data from the West Virginia Department of Health cast a glaring spotlight on the human cost of "prescription opioid prohibition"—a policy that has failed in every tangible way.

Overdose deaths in the state have doubled as illicit fentanyl and other street drugs have replaced the much safer prescription pills. Meanwhile, policymakers and regulators have demonized pain medications, causing real harm to patients. Many patients can no longer access legal prescriptions and instead turn to the streets, where they have an increased risk of death from taking adulterated or counterfeit pills. Policymakers addressed the wrong problem with the wrong tools—and made the crisis worse.

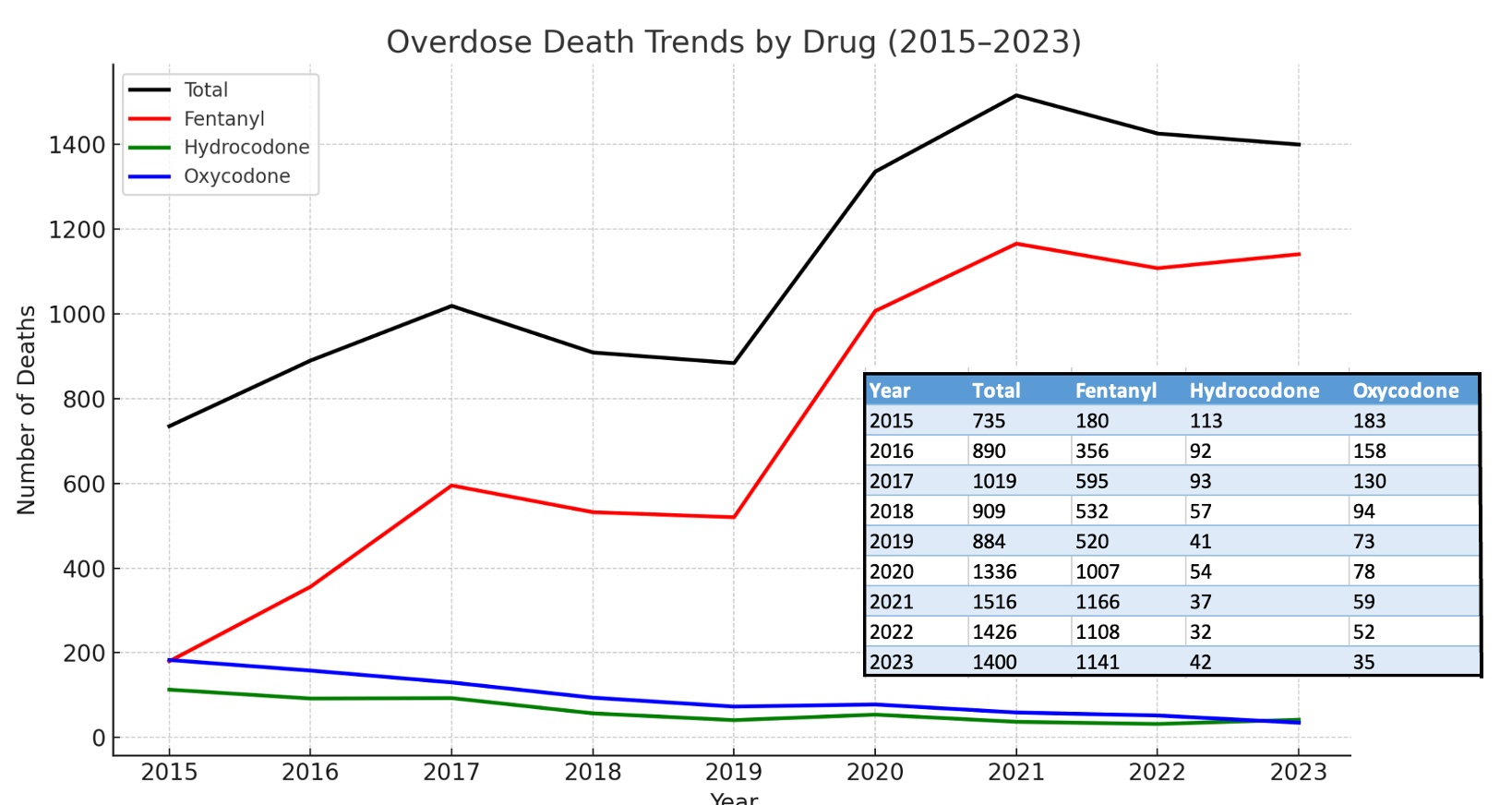

West Virginia Department of Health data illustrate this deadly shift. From 2015 to 2023, as prescription opioid access declined, overdose deaths in West Virginia soared—even though overdoses from prescription medications declined slightly—because users and abusers turned to riskier street drugs.

From 2015 to 2023, despite a decline in opioid prescriptions in West Virginia, overdose deaths doubled. Overdoses involving prescription painkillers such as oxycodone and hydrocodone decreased sharply, replaced by less potent buprenorphine—an opioid used to treat addiction—Celexa, an antidepressant, and gabapentin, which is ineffective as a substitute for pain prescriptions. Even more concerning, methamphetamine and cocaine surged in prevalence, along with fentanyl and xylazine, a veterinary tranquilizer.

West Virginia may be the clearest example, but it's far from the only one. National data show the same pattern. Opioid prescribing peaked in 2010 and has since fallen to levels not seen since the early 1990s. Meanwhile, drug overdose deaths have continued their steady exponential climb—a trend that began in 1979, accelerated during the COVID-19 pandemic, recently returned to pre-pandemic levels, and now appears to be rising again.

The data suggest a clear conclusion: Doctors prescribing opioids like OxyContin were never the main driver of the overdose crisis. Supporting this, a study published in the Yale Law and Policy Review, which used data from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), found that "only 9.0% percent of nonmedical opioid users in 2001 reported ever using OxyContin in their lifetime."

Policymakers adhere to a narrative that conflicts with the data. The data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the SAMHSA reveal no connection between the amount of opioids prescribed and the rates of nonmedical use or addiction. People who misuse opioids aren't the same as patients who rely on them for real pain. Policymakers keep conflating the two, and patients are paying the price. Furthermore, the addiction rate to prescription pain pills among adults aged 18 and older remained below 1 percent during a period when prescription rates doubled, peaked, and then started to decline.

In the early 2000s, nonmedical users sought diverted pain pills. But when policymakers slashed prescribing and dried up the supply, dealers stepped in with heroin, then fentanyl. This was never a crisis of prescribing. It was a crisis of prohibition. And pain patients became the unintended casualties of a failed drug war.

We can't undo the past, but we can prevent further compounding of the mistake. The data are clear: Prescription opioids weren't the main cause of the overdose crisis. Policymakers mistook the harms of drug prohibition for the harms of medical prescribing—and patients paid the price. It's time to reject moral panic and adopt policies based on facts, not fear—policies that address pain without punishing patients.

The post The Real Opioid Crisis Isn't Prescriptions—It's Prohibition appeared first on Reason.com.