In the late 1970s, when I was a fine arts student, the Melbourne University Gallery was just one room in a neo-gothic quadrangle. It wasn’t until the mid 1990s that the university commissioned Nonda Katzalidis to design a four-story concrete gallery on a narrow site fronting Swanston Street.

The Ian Potter Museum of Art quickly became a vital centre for displaying diverse university collections – from classical antiquities to post-war bark paintings and contemporary art.

The re-opening of the museum, after it closed for renovations in 2018, is an art event of major proportions with the architectural clout to match.

The newest addition by Randall Marsh of Wood Marsh Architects transforms an adjacent red-brick building. A polished-steel portal gives onto stylish spaces: high vaulted ceilings, a light-filled atrium, new teaching rooms and luxurious bathrooms. There is now a serious restaurant with a long dining room, open kitchen and balcony café.

Named “Residence” for its annual chef-in-residence program, starting with the Michelin-starred Robbie Noble, this may well become the go-to space for visitors, academics and students alike.

All expectations are exceeded by the opening exhibition 65,000 Years, a Short History of Australian Art. The title emphasises both the ancient Indigenous presence on this continent, and cheekily suggests that the main art that’s been made here is Aboriginal.

As we recognise the monumental contributions of bark painting from the 1940s on, dot-painting from the 1970s on, and urban art starting in the 1980s, there is much to commend this view.

Grand ambitions

The exhibition, in eight main spaces over three floors, has an ambition and scope exceeding landmark surveys such as Dreamings: Art of Aboriginal Australia (1988) and Aratjara: Art of the First Australians (1993).

There is a powerful curatorial will here, led by the legendary public intellectual and Indigenous scholar Marcia Langton, who initiated the project.

She engaged one of the country’s most effective and knowledgeable curators in Judith Ryan, known for her series of field-defining exhibitions over four decades at the National Gallery of Victoria.

Working together with associate curator Shanysa McConville, their exhibition is both politically astute in its management of tough historical issues, and visually stunning. The team has sourced superlative, large-scale examples of major artists’ work from private and public sources to sit alongside the university collections.

It’s an exhibition that repays hours of looking, aided by the curators’ exemplary wall labels. A sumptuously illustrated 340-page tome published by Thames & Hudson Australia for the Potter supports a deeper dive. This includes 23 essays by both Indigenous and non-Indigenous writers who delve into specific groups of work.

An example is the pungent essay by Grazia Gunn, who in 1973 exhibited the University’s rare barks from Groote Eylandt, presented in 1946 by the Jewish refugee Leonhard Adam.

These barks can be seen again in the show, near a masterful assemblage of early barks from Yirrkala, painted in 1937 at the request of ethnographer Donald Thomson. This selection is unprecedented: a dozen barks with complete body designs for mardayin (mens’ ceremony), organised across clan groups.

Truth telling

Throughout 65,000 Years, there is a powerful truth-telling element on frontier wars and massacres. The early recognition of First Peoples’ work as art in the assembled barks goes some way to balancing Melbourne University’s own chapter of shame.

In the side gallery, Langton and team present the role of Melbourne University medical anatomists, eugenicists and physical anthropologists in grave-robbing, and promoting the illicit collection and sale of Aboriginal remains, right up to the mid-1930s.

On a big-screen video Langton, seated in a massive carved cathedral chair like a modern-day Delphic Oracle, dispassionately retells this grisly truth.

The exhibition is comprehensive as it moves across regions and eras in a deft interplay with the building’s shifting levels. The ground floor (bar a stunning atrium enlaced with newly commissioned women’s baskets and “sun-mats”) deals with the imagery of contact from early colonial settlements.

A group of French and British drawings of First Peoples are true portraits in the sense that the sitters are named. Late 19th century colour drawings by Barak or Mickey of Ulladulla are next to rare archival finds: distressing drawings of police reprisals by Oscar (Kuku-Yalanji), from 1898, and six lyrical drawings by Blak inmates of the Darwin Gaol, mounted together under the title “Dawn of Art” for display at the 1888 Melbourne Centenary Exhibition.

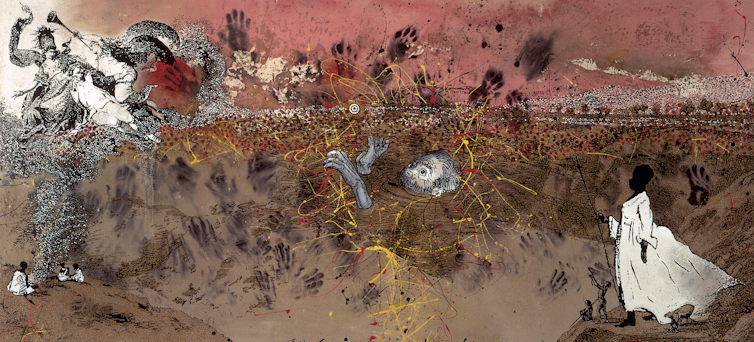

Entering this colonial/decolonial zone, the glowering work of the late, great Gordon Bennett sets the precedent for the current historical citation and appropriation of colonial imagery.

His example has inspired artists from Richard Bell and Brook Andrew to Megan Cope and Daniel Boyd.

Bennett, faithfully represented by Melbourne’s Sutton Gallery through his life, was a McGeorge Fellow at Melbourne Uni in 1993, producing the groundbreaking Mirrorama installation with Groote Eylandt barks in opposition to classical busts. A gentle man and great thinker in art, Bennett then, as now, adds lustre to the Potter.

65,000 Years, a Short History of Australian Art is at the Potter Museum of Art, Melbourne, until November 22.

Roger Benjamin has previously worked as an art selector for the Vizard Collection at the Ian Potter Museum of Art, is an art collector and donor, and a colleague of the exhibition curators; he was not involved in the curation of this exhibition.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.