At this point in his career, Wes Anderson is practically a genre unto himself. But even viewers attuned to his wavelength might find his latest film a challenge. The Phoenician Scheme, a star-studded 1950s espionage farce, is a surprising step backward for the whimsy maestro, whose signature aesthetic has often revealed a hidden thoughtfulness, and a melancholy outlook about the state of things. It’s not that these layers aren’t present here; rather, the issue is Anderson fails to reconcile the growing tension between his surface and subtext, despite a few flourishes that gesture towards breaking through his stylistic constraints. The result might just be his least engaging work.

The film begins in explosive fashion, with mid-air antics befitting classic 007 (What if Wes Anderson directed a Bond movie? Well, now we know). It’s the umpteenth failed assassination attempt against rich industrialist Zsa-zsa Korda (Benicio del Toro), which leads him to reassess his estate. Rather than leaving his wealth to his eight adolescent sons, who live in a dormitory near his mansion, Korda now hopes to make his estranged daughter Leisl (Mia Threapleton) his sole heir, for which he summons her from her nunnery. It just so happens that Korda is widely rumored to have had Leisl’s mother murdered. So, in order to clear his name and win his daughter over, he sets out on a global fact-finding mission which doubles as a protracted business venture. The story’s scattered, episodic unveiling — during which Korda negotiates with various powerful figures played by the likes of Tom Hanks, Riz Ahmed and Bryan Cranston — is broken up by title cards listing the specifics of his conglomerate’s gap financing.

That the film harps on these financial specifics hardly makes for an interesting backdrop, but Anderson makes sincere overtures towards crafting a father-daughter story of reconciliation, with a spiritual twist. Between Leisl’s piety, and Korda’s close calls granting him visions of the afterlife — a stylized venue for cameos from several Anderson regulars, like Bill Murray as the Abrahamic God — The Phoenician Scheme takes on a far more religious bent than the director’s previous works. It often centers the Biblical question of what it would take for a rich man to enter the Kingdom of God, given the tycoon’s ruthless practices.

In a film adorned with facsimiles of ancient Egypt at every turn, the afterlife and judgment loom large in what is, at the very least, a thematically cohesive work. It plays, at times, like a lament for the contemporary state of things, where every industry and facet of life feels like it’s being strip-mined for parts by billionaire self-interest. However, intuiting these themes is one thing. Experiencing them comedically and dramatically is another, and The Phoenician Scheme seldom translates its lingering charms and sorrows through its characters or designs.

For one thing, del Toro feels entirely wrong for the part of Korda, despite the role being written with him in mind. He’s too withdrawn and understated to lead a movie that requires comedic modulation and outward charisma, especially opposite relative newcomer Threapleton, who plays Leisl with a familiar, Andersonian deadpan. A large chunk of the runtime involves exchanges between the father-daughter pair, but there’s never a meaningful enough contrast between their energies to keep things exciting. The punchlines feel drawn out, resulting in awkward cuts and delivery with too much dead air. Despite Alexandre Desplat’s propulsive score in the vein of The French Dispatch, the images here never quite feel as exciting as the music.

On the plus side, Anderson finds a fantastic new muse in the form of Michael Cera, who plays Korda’s meek Genevan tutor Bjørn, a character who exhibits surprisingly charismatic layers. A handful of other recurring Anderson players fill out delightful smaller roles that speak to a larger social fabric — Richard Ayoade as a Marxist revolutionary, and Rupert Friend as a federal spook trying to thwart Korda’s success — making The Phoenician Scheme one of Anderson’s most overtly political works. However, it’s also a film that becomes subsumed by its own political symbols, which hint towards some grand point or realization that never arrives.

Ever since The Grand Budapest Hotel in 2014 — a pastel film about fascism — Anderson has used his carefully composed un-realities to reflect both on his own storytelling, and on the emotional desolation that make his form of whimsy a necessary tool. His most recent feature, Asteroid City, was filled with so much grief that it practically sucked the color out of his usually vibrant frames, as his protagonists fought to stay afloat. There’s far less driving the characters in The Phoenician Scheme (or at least, far less that’s meaningfully expressed), and far fewer moments of artistic self-reflection.

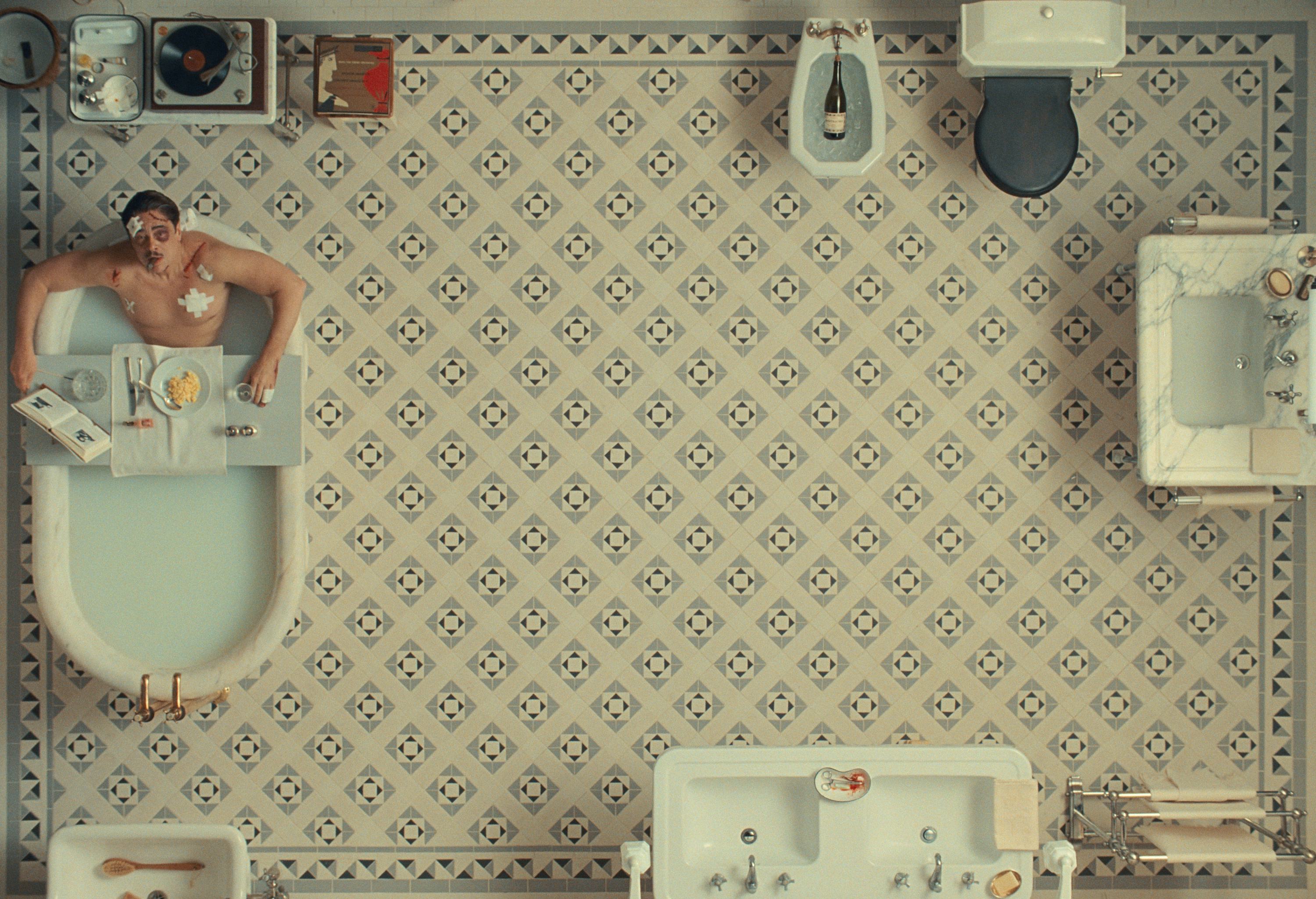

A couple of fleeting shots in the action-heavy final act do, in fact, hint at a creator trying to look past the very walls he’s created. One in particular finds his usual wide angle camera snaking chaotically through one of his symmetrical sets, threatening to break down the façade while contorting its proportions. However, little comes of this beyond the promise that something greater might have been on Anderson’s mind.

More than most of his recent works, a spiritual exploration like The Phoenician Scheme demands artistic introspection and deconstruction, the kind at which Anderson has excelled in the recent past. Instead, what we’re left with is a movie that feels all too content with the ornate surface it weaves. It tightens each bursting seam, pressing back against emotions, themes and instincts that threaten to reveal themselves, resulting in a film that looks familiar, but feels entirely malformed.