It was the most seismic party split in Britain of the post-war area. For a time it seemed that the newly formed Social Democratic Party (SDP), in an alliance with the Liberal Party, really could “break the mould” of politics in the 1980s, as it claimed.

But a combination of internal conflicts, an unhelpful electoral system and a war that helped the Tories recover their popularity ended the dream. After Labour lost power to the Conservatives under Margaret Thatcher in 1979, the party moved to the left, electing Ebbw Vale MP Michael Foot as its leader in 1980 and seeing a rise in the influence of the Trotskyite Militant Tendency.

Four of Labour’s big hitters - former Home Secretary and Chancellor Roy Jenkins, former Foreign Secretary David Owen, ex-Education Secretary Shirley Williams and the less well-known former Transport Secretary Bill Rodgers - left Labour to form the SDP, taking more than 20 Labour MPs with them as well as recruiting one Conservative.

Read more: The smallest church in the British Isles found on a Welsh beach

The split was triggered by a special conference of the Labour Party, which voted to support unilateral nuclear disarmament and to withdraw from what was then known as the European Economic Community (EEC), later the European Union (EU). The new party quickly found itself in the lead in opinion polls, overtaking both the Conservatives and Labour.

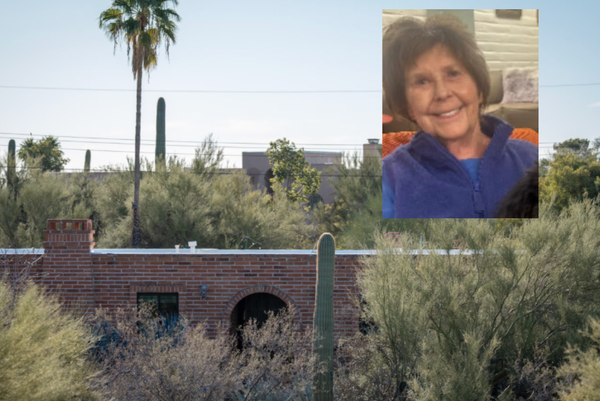

In Wales, one of the founding members of the SDP was Gwynoro Jones, who had been Labour MP for Carmarthen between 1970 and October 1974, fighting three epic election battles with Plaid Cymru president Gwynfor Evans. His newly published book The Forgotten Decade, co-written with former BBC journalist Alun Gibbard, sheds new light on the SDP’s spectacular rise and fall.

Jones’ choice of book title may seem odd, as it covers a decade in which Thatcherite economic policies created mass unemployment in Wales, with the once mighty mining industry reduced to a tiny rump.

What has been forgotten, perhaps, is how fragile the support for Thatcher was before Argentina invaded the Falkland Islands in 1982, precipitating a war in which British jingoism reached heights that have only been rivalled following the recent death of the Queen.

Jones, a lifelong pro-devolutionist, also makes the point that keeping alive the hopes for a measure of home rule in Wales often seemed distant in the 1980s following the devastating four-to-one defeat of a proposal to set up a Welsh Assembly at a referendum in 1979.

Despite the initial poll leads, which led to some spectacular by-election results that saw, for example, Roy Jenkins and Shirley Williams returned to Parliament, the new party quickly developed splits of its own.

Jones writes: “Among the SDP members in Wales there were contrasting views on the Gang of Four [as they were known]. Jenkins was seen as the most successful post-war Chancellor and a statesman of European dimensions, or he was seen as a lazy bon viveur, who hadn’t succeeded as EEC President.

“David Owen was either the tough, charismatic, attractive future leader, or someone who had disappointed as Foreign Secretary and would be the most likely to pose challenges when it came to dealing with the Liberals. Shirley Williams was seen as sincere and approachable, or as indecisive. Bill Rodgers was a strong character and all that is best in the Labour social democratic tradition, or someone that lived in the shadow of the other three and on the sidelines.”

Another enthusiasm dampener was the seemingly endless debate over the nature of the alliance between the SDP and the Liberal Party. Clearly there was no room for two parties to occupy the central ground, but if there was to be a merger when should it take place and in the meantime how would Parliamentary seats be allocated to the parties and how would candidates be selected?

A lot of energy, time and bluster was spent on such discussions, as Jones’ detailed account of the meetings that took place both within the SDP and with representatives of the Liberal Party makes clear. Jones describes attempts by David Owen and his supporters to block an agreement over the allocation of seats that had been reached in Wales between representatives of the SDP and the Liberals.

Referring to a crucial meeting that took place in the autumn of 1984, Jones writes: “David Owen and Shirley Williams had attended at different times on the Saturday. The conversations between the two individuals and me, especially the former, over the Welsh agreement were rather strained.

“The issue would just not go away. I had a private chat with Shirley Williams. She advised me to say little in public until the National Committee next meets so as not to rile David further.

“I got the impression Shirley was on our side. I don’t think she was over-enamoured of Owen’s’ forceful, domineering leadership style. She was trying to cool things down and defer the decision in London.”

From Jones’ point of view, there were also battles to be fought to ensure the SDP was committed to devolution - an ambition that had its detractors both within the Welsh party and the British one. He said that having fought so long for the pro-devolution cause within Labour, he was not prepared to settle for anything less from the SDP.

Ultimately, the game for the SDP / Liberal Alliance was up after the 1987 general election, when the SDP held just five seats and David Owen resigned as leader.

Jones writes: “For me, the central problems revolved around electoral strategy and policy appeal. Throughout the 1980s, I never felt that the SDP and the Alliance were sufficiently radical and reforming enough in their key messaging.

“Most certainly, the Alliance was drawn into arguments as to which party would they support, Conservative or Labour, in the event of a hung parliament. This was a fundamental error. I have never understood why the third force in the political spectrum is always being forced to discuss this trap set for it, time and time again.

“The response should have been: ‘Ask the two old parties first, we are campaigning on our agenda and want to change the face of British politics’. It would have needed a disciplined approach for everyone to maintain that line against a hostile tabloid press and other media outlets and commentators.”

The first past the post electoral system also creates huge difficulties for any party hoping to achieve a breakthrough. At the 1983 general election, the SDP / Liberal Alliance polled 25.4% of the vote but won just 23 seats.

Labour polled slightly better - 27.6% - but won as many as 209 seats, itself seen as a major defeat at the time.

Statistics like that show how difficult it is for new parties to make a significant breakthrough and explain why, despite years of turmoil, Labour hasn’t faced another comparable split since.

The Forgotten Decade by Gwynoro Jones and Alun Gibbard can be bought from Amazon for £15.95.

READ NEXT:

- The smallest church in the British Isles found on a Welsh beach

- King Charles' reign may be shortest ever according to royal expert

- Who wasn't invited to the Queen's funeral? The world leaders and nations who did not attend

- 'Yes Cymru lost its way but I'm determined to get it back on track'

- Some people think Michael Sheen went too far by criticising King Charles for visiting on Glyndwr day