Those who would see the Parthenon marbles return to Greece sense change in the air. As the politics of identity resurge, as the legacies of colonialism are scrutinised, Benin bronzes held in Aberdeen and Cambridge have been sent back to Nigeria, those in Glasgow are the subject of a formal request, and those in Germany are to return too. The Benin bronzes – looted by the British in a punitive raid on Benin City in 1897 – are a very different case from the sculptures that once adorned the great temple of Athens’ patron goddess on the city’s Acropolis, acquired (or so it is argued) legally by Lord Elgin in 1801. But still: Palermo’s Archaeological Museum has just sent its share of the Parthenon sculptures to the Acropolis Museum – on loan, but with talk of a permanent arrangement.

The Palermo sculpture is a shoe-box-size fragment showing part of the goddess Artemis’s foot, rather than the 75m of frieze plus magnificent pediment held in the British Museum, but still, it’s a precedent of sorts. The Greek prime minister, Kyriakos Mitsotakis, made return of the Parthenon marbles a talking point on a recent visit to London. Even the Times has reversed its leader line to support repatriation. “Separating components of an artistic whole is like tearing Hamlet out of the First Folio of Shakespeare’s works,” says its editorial – though bringing the Bloomsbury sculptures to Athens would not complete anything at all, since half of the stonework is destroyed, and they will never be intact again.

To many British people – among whom restitution, according to a recent YouGov poll, is popular – restoring the sculptures to Greece seems simple. The Greeks want them, they were made in and for Athens, they should go back. Indeed, their presence in Bloomsbury has always been bitterly controversial, right back from the parliamentary debate in 1816 in which it was pondered, among many other things, whether Lord Elgin had taken advantage of his position as ambassador to acquire the firman, or permit, from the Ottoman authorities to abstract “qualche pezzi di pietra” (“any bits of stone”) from Athens’ Acropolis (the document survives only in Italian translation).

That’s before you start to consider whether Elgin went beyond the terms of the firman – and whether, even if you think he was acting lawfully, that’s the point, given how many terrible things through history have been done within the rule of law. The case for return has seemed all the more compelling since the 2009 opening of the Acropolis Museum, whose airy galleries, in sight of the temple itself, do such a wonderful job of telling the story of the Parthenon. By comparison, the British Museum’s Duveen Gallery can seem bleak and depressing.

So why doesn’t philhellene Boris Johnson just give them back? After all, as a student he wrote passionately in favour of restitution. Well: what Johnson may or may not have thought once is, naturally, irrelevant (see also: Brexit and the BBC licence fee). Much more pertinently, he can’t: national museums in Britain are not an extension of government, they are at arm’s length and independent from it. In a rare outbreak of continence, Johnson has said that the Parthenon sculptures are a matter for the trustees of the British Museum.

These trustees, who include Mary Beard, Grayson Perry and chair George Osborne, are the “owners” of the BM’s collection – in the sense that they hold it in trust for the public. The 1753 act of parliament that set up the museum defined “the public” as “all studious and curious Persons” – including “all learned Foreigners”.

It’s not impossible, then, that the trustees might wake up one morning and decide that the Parthenon sculptures would render most benefit to the public if they were displayed in the Acropolis Museum. In fact, I think they would be unlikely, at least in the short term, to do so. One reason is that trustees of institutions such as the British Museum are, collectively, constitutionally unsuited to taking radical decisions, however independent-minded they may be individually. Another is ideological: the museum asserts the centrality to its collection of the sculptures and argues there is huge benefit in their being displayed near Assyrian and Egyptian art, an arrangement that highlights the interconnectivity between cultures, as would not be the case in Athens.

A third reason is the law. The 1963 British Museum Act and its amendments state that the trustees cannot deaccession collection items except under very specific circumstances: if they are degraded or riddled with pests, if they are “duplicates”, or if they are deemed by the UK’s Spoliation Advisory Panel to have been looted or bought under duress during the Holocaust. And so the situation circles, perhaps conveniently. It’s not up to the government, it’s up to the trustees. And yet it’s not up to the trustees, because of the law. And it can’t lend to the Greeks, because the Greeks don’t recognise the British Museum’s ownership of the sculptures. Museums, on the whole, don’t lend things without certain conditions being met – most importantly, that they would be able to get them back. Hence the impasse, the convenient continuance of the status quo. The sculptures, though more ancient than either concept, are embroiled in the history of the nation state and of museums, and tangled in a knot of legal trusteeship and ownership.

In the early years of this century, Neil MacGregor, the former director of the British Museum, made a strong case for the British Museum as a “universal” museum based on Enlightenment principles. It was a place of the world, for the world, he said. The collection could be mobile, lending its treasures to Britain and around the globe (in 2014, with some chutzpah, the museum even lent one of the Parthenon sculptures to St Petersburg). In Nairobi in 2006, attending the first exhibition in Africa to which the BM had lent objects, MacGregor told me – and I still recall his testiness, unusual given his normal charm – that “repatriation is yesterday’s question”. Not all Kenyans, it was clear to me, were so certain.

A decade and a half on, MacGregor, I think, would concede that restitution is, in fact, today’s question. The universal museum is not a neutral concept. The British Museum is the product of a combination of curiosity, scholarship and rampaging imperial acquisitiveness. But if museums are sites that represent some of the most troubling legacies of empire, they can and should also be places where these issues can be worked out – or to use a more recent formulation of MacGregor’s, “sites of atonement and reconciliation”. They have a duty to act ethically.

The sensible course is for the government to institute an expert panel to hammer out principles on which repatriation claims to national museums can be soberly assessed, as has now long been done for artefacts linked to the Holocaust. The Westminster government with its wilful nativism seems unlikely to be minded to do that. But repatriation is today’s question. And almost certainly tomorrow’s, too.

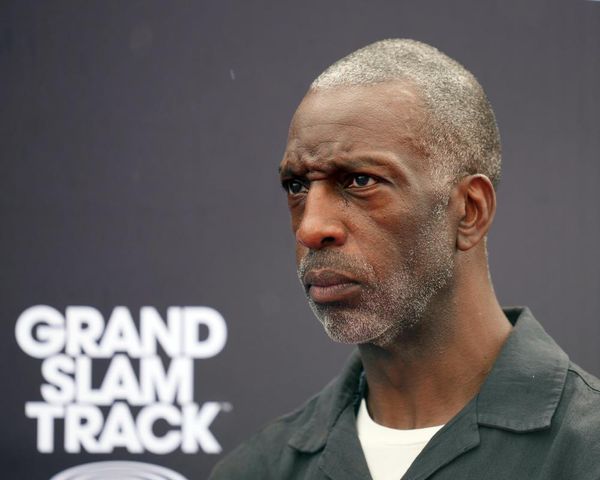

Charlotte Higgins is the Guardian’s chief culture writer