Most books about Hong Kong cinema focus either on film history or how movies reflect the society and politics of the city. But two books on Hong Kong action cinema, one relatively old and one relatively new, take beguilingly different approaches.

Planet Hong Kong, by US-based film professor David Bordwell, focuses on film style and aesthetics, and uncovers the filmmaking techniques that make Hong Kong action movies unique.

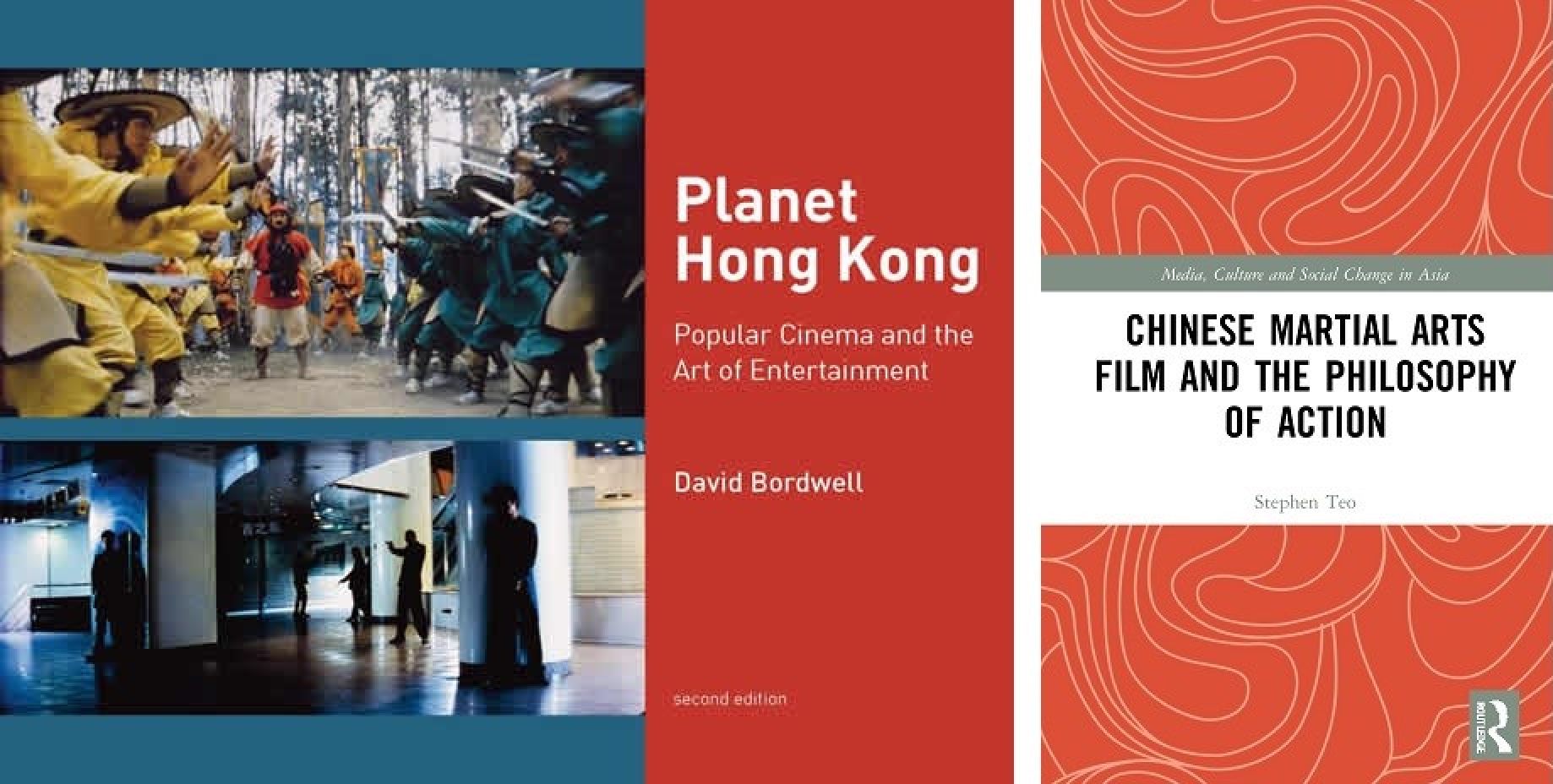

Chinese Martial Arts Film and the Philosophy of Action, by leading academic Stephen Teo, who specialises in wuxia movies, is a fascinating riff on how martial arts films can elucidate the wider realm of Chinese philosophy.

Both books expand the understanding of the martial arts genre.

Being a stunt double for Bruce Lee made Jackie Chan want to be a star

Planet Hong Kong

David Bordwell is well known in Hong Kong film circles. His 2000 book Planet Hong Kong does cover film historical topics, but devotes most of its pages to a breakdown of the way Hong Kong films are made.

Bordwell looks at the camerawork and the editing of Hong Kong action films, and distinguishes how the practices differ from those of films made elsewhere. He also looks as how the commercial demands of the Hong Kong film industry have shaped the filmmaking practices of directors.

Any filmmaking student wishing to make an action film in the Hong Kong style could learn a lot from his book.

Bordwell’s work is refreshingly straightforward. Hong Kong films look different because they are different, he says. For instance, the edits are faster than in films from other countries. Editing sped up in the 1970s to keep the attention of the audience – a director’s main aim was to keep the audience in their seats during midnight shows – and continued to get faster, he says.

“By the early 1990s, an average of four to six seconds per shot was normal in all genres,” he writes. “Action scenes, which could hardly get any faster, did. The climactic fight between Bruce Lee and the Japanese villain in Fist of Fury rattles along at 2.7 seconds a shot, but the parallel scene in the quasi-remake Fist of Legend not only lasts three times as long, but has an average shot length of merely 1.6 seconds,” he notes.

Bordwell also correctly notes that if you watched a film in Hong Kong at that time, it might have seemed even faster, as projectionists ran the film through the camera not at 24 frames per second, but at 26 fps or even 28 fps to squeeze in more screenings – something to which this writer can attest!

The main goal in Hong Kong cinema, in Bordwell’s view, was to keep the audience glued to the screen by depicting motion. The only time people stay still in Hong Kong action films is when they are dead – and sometimes, not always then.

Movement holds the eye, and the much disdained zoom shots use in martial arts films were just another attempt to keep things moving, Bordwell writes in the book, which has been published in a Chinese translation.

Chinese Martial Arts Film and the Philosophy of Action

Stephen Teo wrote the standard English-language work on Hong Kong film history, Hong Kong Cinema: The Extra Dimensions. He has also written widely on wuxia films, authoring the book Chinese Martial Arts Cinema: The Wuxia Tradition, a detailed history of the genre.

His latest book is a beautifully elegant discourse on the relationship between martial arts films and traditional Chinese philosophy.

The work is wonderfully idiosyncratic: it does not seek to show how martial arts filmmakers were informed by Chinese philosophy – for instance, by a knowledge of the fighting Buddhist monks of the Shaolin Temple – but how their films can be used to illustrate aspects of Chinese philosophy.

The book’s dual focus on ancient philosophy and film won’t be for everyone, but this is certainly a unique take on the genre.

Teo picks six films and then proceeds to show how they can illustrate the ideas of the three main Chinese philosophies, Buddhism, Taoism, and Confucianism, and lesser known ones like Mohism.

He makes the text more vibrant with his wise decision to use as examples films from the 21st century, rather than the acknowledged classics: Hou Hsiao-hsien’s The Assassin, Zhang Yimou’s Shadow, Tsui Hark’s Seven Swords, Wong Kar-wai’s The Grandmaster, Xu Haofeng’s The Final Master, and Wu Jing’s Wolf Warrior 2.

As martial arts fans are aware, there’s a contradiction at the heart of wuxia movies: the xia (knights) are honourable individuals who wish to do good, but they must kill to achieve that good, and killing is universally considered bad. Martial artists adhere to Confucian values, but must diverge from them by committing violence to uphold them.

Teo’s essay on Hou’s The Assassin says that the film provides something of a solution in the way that the killer gradually moves to use non-violent means to achieve her goals, noting that it expresses the Taoist idea of wuwei, or “non-action”.

More importantly for Teo, the gradual moral development of Shu Qi’s female assassin can be used to illustrate the three main philosophies: Confucianism, Taoism and, finally, Buddhism.

The author also feels that Wong Kar-wai’s The Grandmaster can be used to illustrate a Buddhist idea, that of the impermanence of all things. He thinks this is shown by the continually shifting relationship between Ip Man (Tony Leung Chiu-wai) and Gong Er (Zhang Ziyi), the female master of the 64 Hands technique who beats him in a duel.

“In The Grandmaster, it is the central relationship between Ip Man and Gong Er that reiterates impermanence,” Teo writes, and adds that “Wong can be recognised as a Buddhist auteur.”

In this regular feature series on the best of Hong Kong martial arts cinema, we examine the legacy of classic films, re-evaluate the careers of its greatest stars, and revisit some of the lesser-known aspects of the beloved genre. Read our comprehensive explainer here.

Want more articles like this? Follow SCMP Film on Facebook

!["[T]he First and Fifth Amendments Require ICE to Provide Information About the Whereabouts of a Detained Person"](https://images.inkl.com/s3/publisher/cover/212/reason-cover.png?w=600)